Last term, the conservative justices delivered an astonishing expansion of executive power. Now the consequences could render them irrelevant.

By

Mark Joseph Stern

Enter your email to receive alerts for this author.

Sign in or create an account to better manage your email preferences.

Are you sure you want to unsubscribe from email alerts for Mark Joseph Stern?

Unsubscribe from email alerts

May 27, 20255:40 AM

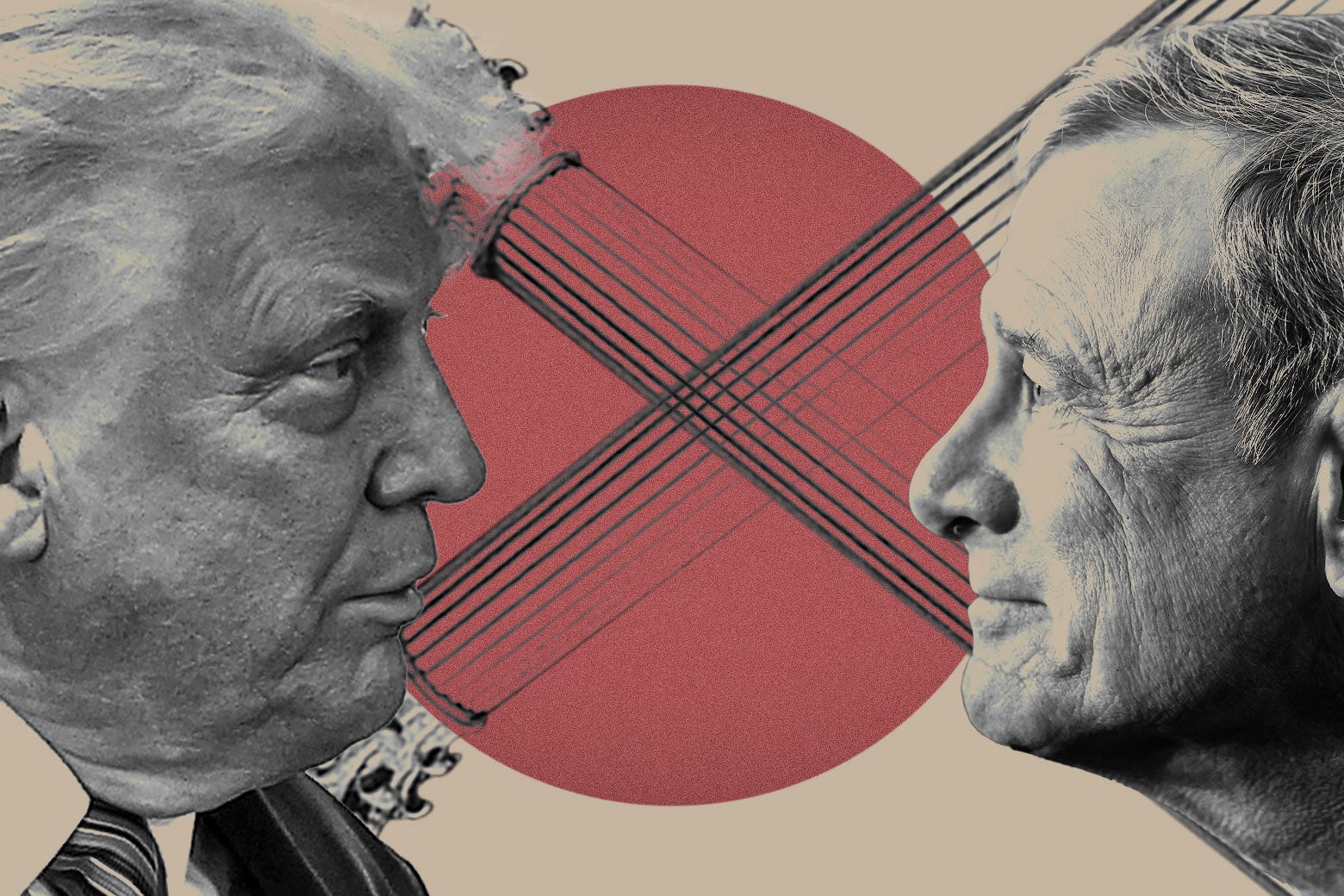

As the first Supreme Court term of Donald Trump’s second presidency draws to a close, one particularly alarming throughline has emerged: The court’s decision in Trump v. U.S. nearly one year ago has emboldened the president to challenge the limits of judicial authority to their breaking point. The Supreme Court’s 6–3 decision granting Trump sweeping immunity from criminal prosecution looked disastrous from the moment it was released in July 2024. Its impact has only grown more dire since then, as a string of emergency orders and late-night rulings from the court in response to Trump’s daily assaults on the Constitution makes plain. At the time, the most immediate consequence of Trump v. U.S. appeared to be its derailment of special counsel Jack Smith’s effort to try Trump for his attempted subversion of the 2020 election. And that outcome undoubtedly bolstered Trump’s successful campaign to retake the White House by taking a Jan. 6 trial off the table before November 2024.

But the more enduring ramifications only became clear after he reentered the White House in January. In the course of effectively exonerating Trump for his misdeeds, the Supreme Court endorsed a corrupt vision of the presidency in which self-dealing, partisan retribution, and abuse of power were reframed as legitimate, even laudable constitutional prerogatives of the chief executive. Trump’s second administration has, predictably, embraced this cynical conception of executive authority, with devastating results for democracy and civil liberties. In a matter of months, it has transformed the office of the president into a monarchical perch. Trump himself has weaponized the decision to assert unprecedented control over the government and exact unlawful retribution against its perceived enemies, in ways that even the majority probably did not foresee—from his successful efforts to bring major law firms under heel to his campaigns against Ivy League schools and student protesters, to his unlawful renditions of undocumented immigrants to a brutal Salvadoran prison under the false pretense that they are part of an invading army.

The majority may have also failed to foresee the ways that Trump would use the decision to diminish the court’s own power. Having freed the president to burst past existing constitutional restraints, the justices must now try to preserve their own authority from executive encroachment. In case after case since Trump’s restoration, the court has tried to have it both ways, reeling in some of his most extreme actions—while still giving the GOP most of what it wants—without entirely ceding its own power to tell the president “no.” And so a malignant dynamic is now unfolding between an imperial court and the president whom it crowned “a king above law.” The conservative supermajority continues to pursue its own agenda, which includes an aggressive expansion of executive authority. But it is doing so at the worst possible time, when the presidency has been captured by an aspiring authoritarian who defies all constitutional constraints. So the Supreme Court is caught between its own desire to shift the law rightward and its fitful inclination to shoot down Trump’s most extreme moves—if only to preserve its own power.

How did we get here? In retrospect, it should have been obvious that Chief Justice John Roberts would leverage the immunity case, Trump v. U.S., to expand presidential power. Roberts has long been a devotee of the “unitary executive theory,” the notion that Article 2 of the Constitution gives the president almost absolute control over the entire executive branch. A growing mountain of evidence has proved that this theory is rooted in an egregious misreading of history, but the chief justice and his conservative colleagues have kept the faith. And they used Trump v. U.S. to pass off, as settled law, a set of deeply contested claims about near-dictatorial presidential power.

At the heart of the ruling, of course, was Roberts’ infamous declaration that the president may not be prosecuted for his “official acts” in office—that is, “actions within his conclusive and preclusive constitutional authority.” This supposed guarantee does not actually appear in the Constitution itself; Roberts largely made it up based on his own beliefs about how the government should operate. He then applied his newfound rule to Trump’s indictment, insulating him from charges that allegedly qualify as “official acts.” In the process, he decreed that a huge swath of Trump’s actions after the 2020 election—many the subject of his second impeachment—were, in fact, protected by Article 2.

As Harvard Law’s Jack Goldsmith has detailed, Roberts then went much further: He declared that much of the president’s misconduct was not only immune from prosecution, but also from any kind of regulation or oversight by Congress or the courts. By doing so, the chief justice placed a patina of constitutional legitimacy over Trump’s conspiracy to steal the 2020 election, announcing that some of his most notorious abuses of office could not be halted or punished by the other branches, except through impeachment and removal. These novel claims, Goldsmith points out, were not even briefed by the parties or addressed by the lower courts. It appears that the chief justice simply spotted an opportunity to enshrine them into precedent and decided to shoot his shot. This rushed and reckless approach created a roadmap that Trump would easily exploit from the moment he returned to the White House.

Consider, for instance, how the ruling analyzes Trump’s meddling with the Department of Justice after the 2020 election. It acknowledges that the president and his allies pressed the agency to open criminal investigations into the voting procedures in key swing states that Joe Biden carried. Under this plan, the DOJ would pretend to uncover election fraud in these states, then urge their legislatures to create an “alternative slate” of electors who would cast their votes for the losing candidate, Trump. When then–acting Attorney General Jeffrey Rosen refused to go along with the scheme, Trump threatened to fire him. Smith’s indictment zeroed in on this scheme to support his allegation that the president engaged in an unlawful conspiracy to thwart Congress’ certification of the election.

But Roberts held that Trump’s demands for a sham investigation were constitutionally protected. Why? Because, he wrote for the court, the president has “exclusive authority over the investigative and prosecutorial functions of the Justice Department and its officials.” Roberts then reframed Trump’s invidious interference with the DOJ as a permissible exercise of executive authority. This kind of “decisionmaking,” he insisted, is “the special province of the executive branch,” and the president himself holds all “executive power.” He therefore holds “exclusive authority and absolute discretion to decide which crimes to investigate and prosecute, including with respect to allegations of election crime.” He may also “discuss potential investigations and prosecutions” with subordinates—a euphemism for conspiring with loyalists to overturn the election. And he must have “unrestricted power to remove the most important of his subordinates” for refusing to obey his will, no matter how corrupt or outright criminal.

It is unclear whether, when writing these passages, the chief justice realized he was blessing a shocking expansion of presidential power. The Justice Department has long operated with a substantial degree of independence from the White House to ensure that it wields its immense power free from partisan interference. President Richard Nixon notoriously breached this wall during Watergate, prompting both Congress and the DOJ itself to enact reforms that would insulate federal law enforcement from direct presidential control. Yet in Trump v. U.S., Roberts spurned the very principle of DOJ independence as an affront to the Constitution.

Georgetown Law’s Marty Lederman promptly flagged that holding as a “profound” shift in the law, one that will be “weaponized” by “executive branch lawyers and officials for time immemorial.” He also noted that this new rule is not limited to the Justice Department, but seemingly applies to all federal agencies, many of which have their own law enforcement operations. Roberts essentially decreed that Congress may no longer bar the president from corrupting these agencies by instructing them to open fraudulent investigations and lie to the public. That is, Lederman warned, “an extraordinarily radical proposition”—a loaded gun that an unscrupulous president could easily brandish to shoot down the rule of law.

Which is exactly what Trump is now doing. Central to his consolidation of power since Jan. 20 has been his assertion of total control over the Justice Department, the Department of Homeland Security, and other federal law enforcement agencies. And he has used this control to further his own campaign of retribution. Trump has, for example, ordered the DOJ to launch criminal probes into two first-term officials who publicly criticized him. (One target’s offense: Acknowledging that the 2020 election was free and fair.) Trump has issued a slate of executive orders against law firms that have hired or represented people he dislikes, instructing his administration to investigate and penalize them. He has unlawfully retaliated against news organizations whose speech he disapproves of. He has directed his administration to investigate and potentially punish universities that he views as overly liberal. And he has empowered his subordinates to imprison and attempt to deport student protesters on the basis of their protected free speech.

Trump has been able to do all this because he has torn down the traditional buffer between the White House and the Justice Department—with the eager assistance of Attorney General Pam Bondi, who views herself as the president’s personal lawyer. So, too, do Trump’s rotating cast of interim U.S. attorneys, including Ed Martin and Alina Habba, who believe it’s their job to carry out the president’s wishes by using the vast powers of their offices to target his political enemies and exonerate his friends. And why shouldn’t they? True, decades of institutional norms counsel against such interference on the grounds that the Justice Department serves the law, not the president. But the Supreme Court has now dismissed those customs as an encroachment upon executive power. It was inevitable that Trump would interpret its decision as permission to transform the Justice Department into an arm of his authoritarian project.

Nor does any of this stop at the Justice Department. Roberts’ endorsement of presidential removal power in Trump v. U.S. constituted, in Lederman’s words, a “stealth overruling” of a Supreme Court precedent upholding congressional restraints on the firing of law enforcement officials. One week into his second term, Trump exercised this power to illegally fire 17 inspectors general, violating congressional restrictions on the removal of these independent watchdogs. The move hobbled internal checks against fraud and abuse across agencies. But the courts did not stop it—after all, inspectors general perform law enforcement duties, a responsibility that SCOTUS pronounced to be “the special province” of the president. Trump and his allies have also asserted a broader and unprecedented right to purge much of the civil service, including prosecutors who worked on Jan. 6 cases. Trump’s DOJ threatened to clear out a U.S. attorney’s office until it could find someone who would corruptly suspend the prosecution of New York Mayor Eric Adams for purely political reasons.

Look closely, and you can see Trump v. U.S.’s impact all across the government. The president’s ability to suspend the TikTok ban, a ban that the Supreme Court unanimously upheld, derives from the chief justice’s declaration that the president alone can enforce, or not enforce, federal law. Trump’s top advisers are repurposing the Trump v. U.S. ruling to justify “impounding,” or refusing to spend, billions of dollars appropriated by Congress—something Congress has expressly prohibited. The government’s unlawful efforts to summarily deport migrants to a Salvadoran prison is also tied to the ruling: The Justice Department has proclaimed that, as president, Trump has inherent constitutional authority to deport immigrants without due process. For support, it has cited a passage in Trump v. U.S. granting the president expansive power over “matters related to terrorism” and “immigration.” The administration argues that this language, alongside Roberts’ other proclamations of executive control, prevents Congress and the courts from interfering with his mass deportation plans. For Trump, the ruling is the gift that keeps on giving.

But how does the Supreme Court feel about all this? Goldsmith is likely correct that the majority did not think through all the implications of its decision for a second Trump term. (Partly, it may have been a matter of haste; the court rushed out the monumental ruling in barely two months.) Roberts and his conservative colleagues also may not, for example, mind the firings of executive branch officials, since beefing up that power has been part of the conservative project for decades.

SCOTUS, though, has blocked a number of moves that Trump undertook based, at least in part, on his administration’s interpretation of Trump v. U.S. The court forced the Department of State to pay out $2 billion in foreign aid that the government tried to impound. It ordered the government to attempt to retrieve a migrant who was mistakenly deported (a ruling the executive branch continues to defy). It halted the late-night removal of Venezuelan migrants then ruled that their due process rights had been violated. Roberts himself has rebuked Trump’s call for the impeachment of judges who rule against him.

Yet this pushback is intermittent and often half-hearted, reflecting an ambivalent attitude to the precedent-shattering president. Although the court did ultimately protect Venezuelan migrants from summary deportations, it first gave the administration a technical victory lifting a restraining order that had halted their removal. Its decision in favor of the wrongly deported migrant also struck a pose of compromise, deferring to the executive branch’s primacy over foreign affairs—creating a loophole that the government has used to disregard its order. The court seems unlikely to uphold Trump’s assault on birthright citizenship, but may split the baby by rolling back the nationwide injunctions that are the sole thing keeping the policy on hold. And while just last week it blessed his firings of independent agency heads, it tried to preemptively carve out an exception to its ruling that prohibits him from taking over the Federal Reserve, clearly an area of special concern to the court.

The majority seems at once delighted that Trump is creating opportunities to shift the law rightward yet distraught that he sometimes pushes to the point of encroaching on the court’s own power. Its solution, for now, is to continually stake out middle ground when conflicts between the two branches’ agendas arise. By doing so, the court is all but encouraging the administration to test, if not blow past, the limits of its own decisions. It has repeatedly endorsed the president’s interpretation of Trump v. U.S. as a near-boundless grant of executive authority. No one should be surprised when Trump concludes that the bounds of his power extend well beyond the Supreme Court’s own rulings.

There is a deep irony at the root of this emerging conflict. No institution played a bigger role in handing Trump the power he is now abusing than the Supreme Court itself. Now, after paving his path back to the White House and dismantling limitations on his power, SCOTUS appears increasingly uncomfortable with how he is using his authority. Its concerns may arise in no small part from the fear that the Trump administration is sapping the judiciary of its strength, defying courts’ orders, and treating their decisions as advisory at best. Some of the conservative justices may be perturbed that the White House is effectively demoting the judiciary from a co-equal branch of government to a bothersome layer of bureaucracy that can be overridden or ignored. If so, the blame for surrendering the court’s legitimate claim to equal authority falls squarely on the court’s own shoulders.

Sign up for Slate's evening newsletter.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·