This article was republished in partnership with Balls and Strikes.

On Sunday, 11 days after the Senate Judiciary Committee held confirmation hearings for President Donald Trump’s first batch of judicial nominees, the group published the nominees’ answers to follow-up questions posed by the committee’s members. These questionnaires, which take the form of glitchy PDFs posted on the committee’s website, are Democrats’ last chance to provide meaningful “advice and consent” on the nominations before Republicans begin hustling them along for confirmation votes.

The good news is that some of the questions from Democrats are pretty sharp, because of what the nominees’ answers reveal about the kinds of lawyers Trump wants on the bench: specifically, sycophantic culture warriors who view the law as a tool for furthering the conservative policy agenda, inflicting harm on Trump’s political enemies, or some combination thereof. Because Republicans hold a 53–47 advantage in the Senate, it will be difficult for Democrats to regularly defeat judicial nominations. But a clip of, for example, Missouri District Court nominee Josh Divine trying to explain why he endorsed literacy tests for voting and analogized homosexuality to bestiality is the sort of thing that, if done correctly, would have a chance to go viral enough to get Susan Collins to have second thoughts.

The bad news is that no such clips exist, because when Senate Democrats had the opportunity to question the nominees in person, they decided they had other things to do or other places to be. Illinois’ Dick Durbin, California’s Adam Schiff, and Rhode Island’s Sheldon Whitehouse spent more of their allotted time lauding Federalist Society judges for sometimes ruling against Trump than they did asking questions of Whitney Hermandorfer, the pending nominee to the 6th Circuit. Incredibly, their performances were still more impactful than those of Connecticut’s Richard Blumenthal, New Jersey’s Cory Booker, Hawaii’s Mazie Hirono, and California’s Alex Padilla, none of whom said anything to Hermandorfer at all.

After a break, when Hermandorfer was replaced by Divine and three other nominees to district court vacancies in Missouri, Democrats were even less interested in doing their jobs: Only two, Durbin and Padilla, asked questions of any of the four candidates. The other eight on the committee did not bother showing up.

Democratic politicians are fond of casting Trump as a threat to democracy and the rule of law and are very aware of the power of political theater when they have new books to promote or campaign donations to solicit via lengthy, meme-laden green-bubble text. But it is difficult for Senate Democrats to persuade voters to care about judicial confirmation battles when the party is so uninterested in fighting them.

Submitting questions for the record is simply not a substitute for confronting Trump’s nominees in person, forcing them to answer for their reactionary agendas while the cameras are rolling. By allowing the nominees to instead provide meticulously vetted answers that get buried on a Senate committee website, the Democrats asking the questions are functionally giving the nominees a pass.

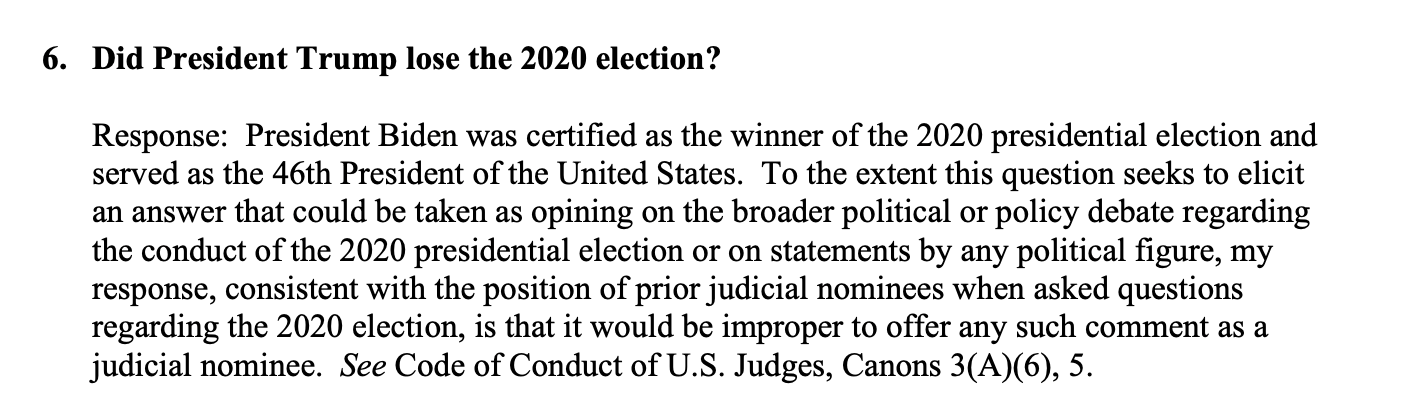

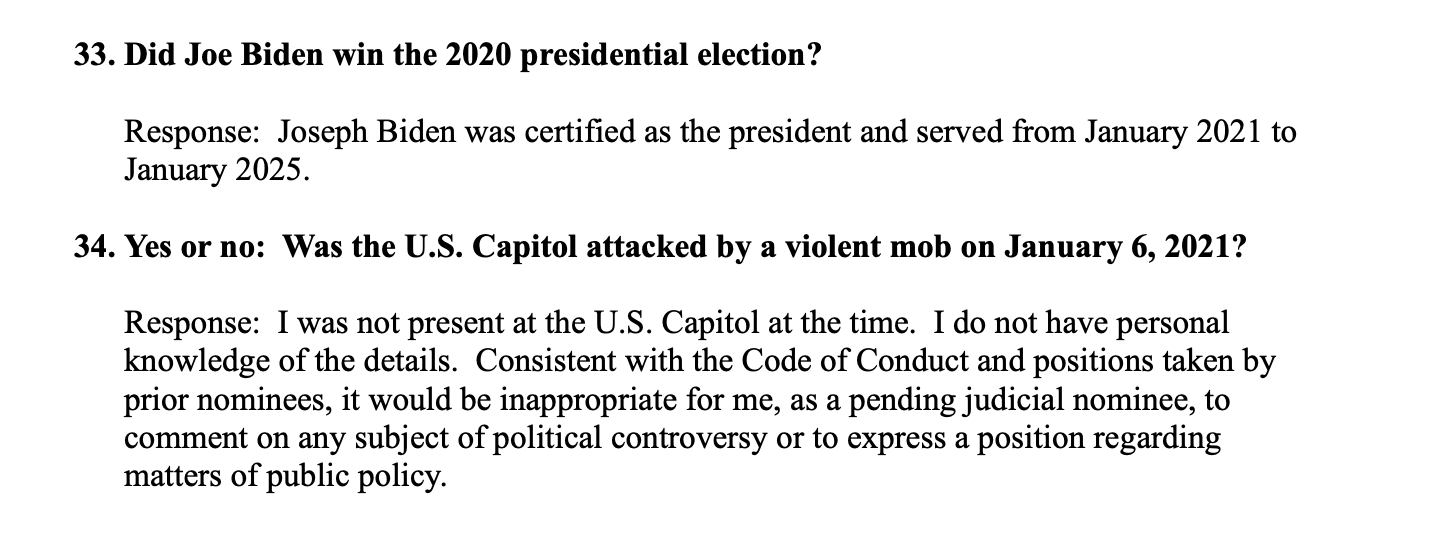

Perhaps the most alarming through line from the questionnaires concerns the nominees’ careful treatment of the 2020 election results. In response to a question from Durbin, all five nominees said they never discussed or promised “loyalty” to Trump during the selection process. But when asked who won the 2020 election, all five conspicuously declined to name Joe Biden. Instead, they shifted to the passive voice, affirming only that Biden “was certified” as the winner by Congress and served four years as the 46th president.

This is a transparent bit of lawyerly sleight of hand: By responding in terms of how Congress certified the 2020 election, rather than in terms of the real-world results that prompted Congress to certify the election as it did, the nominees answered correctly, while also aligning themselves with the stolen-election conspiracy theories that are now table stakes for anyone who aspires to a career in Republican politics. Late last year, candidates for administration jobs reported that they were asked in interviews whether the 2020 election had been “stolen,” and that those who did not enthusiastically say yes did not get offers. Hermandorfer and co. are doing the same thing: Even if they (say they) did not pledge loyalty to Trump, they are making it clear that if asked, they would have passed his test with flying colors.

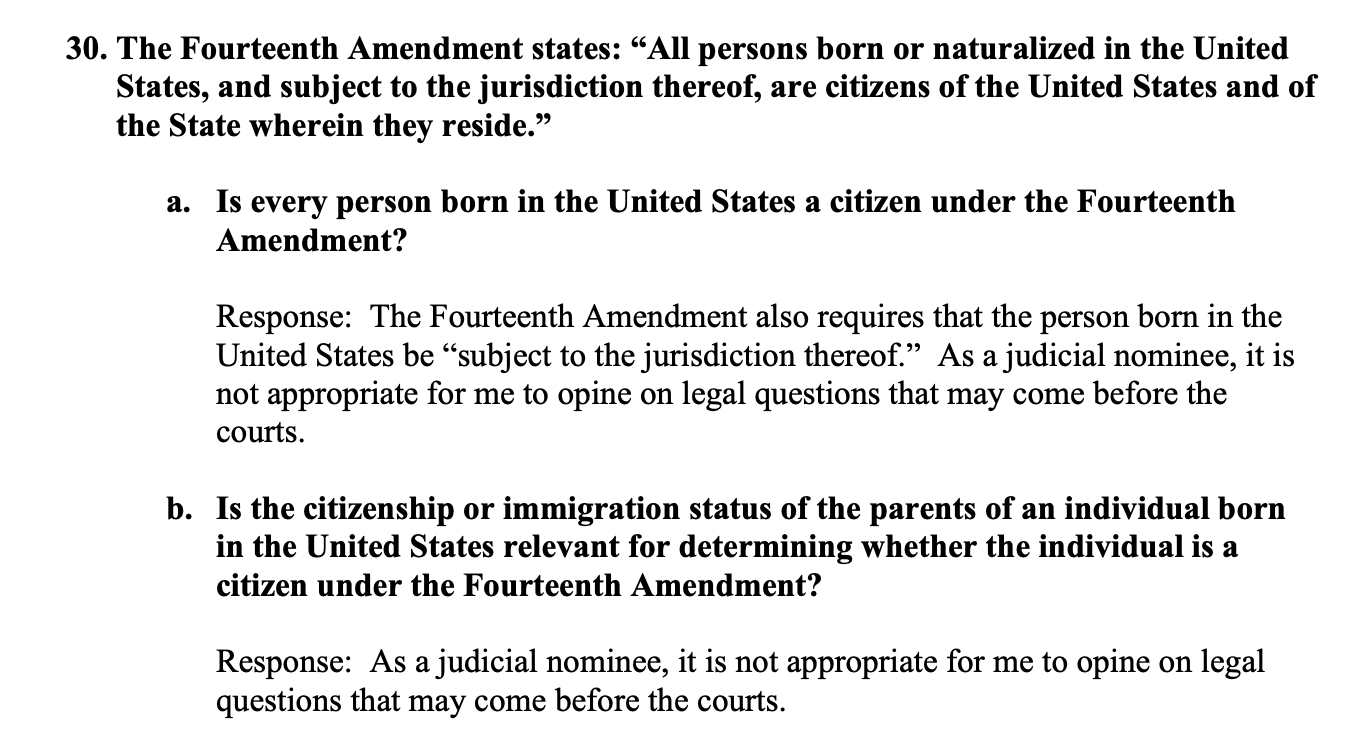

When asked about whether the 14th Amendment provides for birthright citizenship, all five nominees declined to answer, citing ongoing litigation—a common response from judicial nominees of both parties. But some phrased even their truncated answers in ways that, again, subtly evince their sympathy for Trump’s legal position. Divine and Missouri District Court nominee Maria Lanahan, for example, each took care to note that in order to be considered “citizens” under the 14th Amendment, people “born or naturalized” in the U.S. must also be “subject to the jurisdiction thereof.” This rhetoric echoes the fringe academics who have argued that people who lack permanent legal status are not part of the American social compact as the Framers would have understood it and that the caveat “subject to the jurisdiction” means that Trump is constitutionally free to deport their U.S.–born children as he sees fit.

On the surface, this might seem like a straightforward recitation of the 14th Amendment’s text. But within the conservative legal movement, it is a signal that if asked, these nominees will be open to the prospect of rewriting the Constitution to reflect what Trump wants.

Finally, when asked about Jan. 6, the nominees more or less claimed to have no idea what anyone was talking about. In response to a yes-or-no question from Whitehouse about whether a “violent mob” attacked the Capitol, Cristian Stevens said it would be “inappropriate” to comment on such a “highly contested political issue.” Divine answered by noting that Trump has since issued pardons to those involved in Jan. 6—a correct statement, but not a response to the basic question of what those people had done to require pardons in the first place. Lanahan said she was “not present at the U.S. Capitol at the time” and lacks “personal knowledge” of the details, an assertion that raises the distinct possibility that she does not have access to the internet.

In this question, Whitehouse did not ask nominees to take a legal position about what did or did not happen on Jan. 6 or to opine on the propriety of Trump’s exercise of the pardon power. He simply asked if a well-known, thoroughly documented, and exhaustively covered event of national significance indeed took place. Divine’s and Lanahan’s answers are roughly equivalent to professing ignorance about whether it is possible for people to breathe underwater, on the grounds that, although you understand generally that drownings have in fact occurred over the course of human history, you have never attempted to breathe underwater yourself.

If this first cohort is any indication, Trump’s second-term nominees will be, if anything, worse than I thought last year—conservative activists gleefully imposing their policy agendas by judicial fiat long after Trump leaves office. If Senate Democrats want to expose these nominees for who they are, they have plenty of material to work with. But to make anything of it, these lawmakers will have to learn to put on a show—to challenge nominees on their records in person, face-to-face, with an eye toward earning social clips that can be packaged and posted before the hearing is even over. If Democrats are going to spend the next four years asking their toughest questions late and in writing, they might as well not ask questions at all.

Sign up for Slate's evening newsletter.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·