By Aziz Huq

June 04, 202512:43 PM

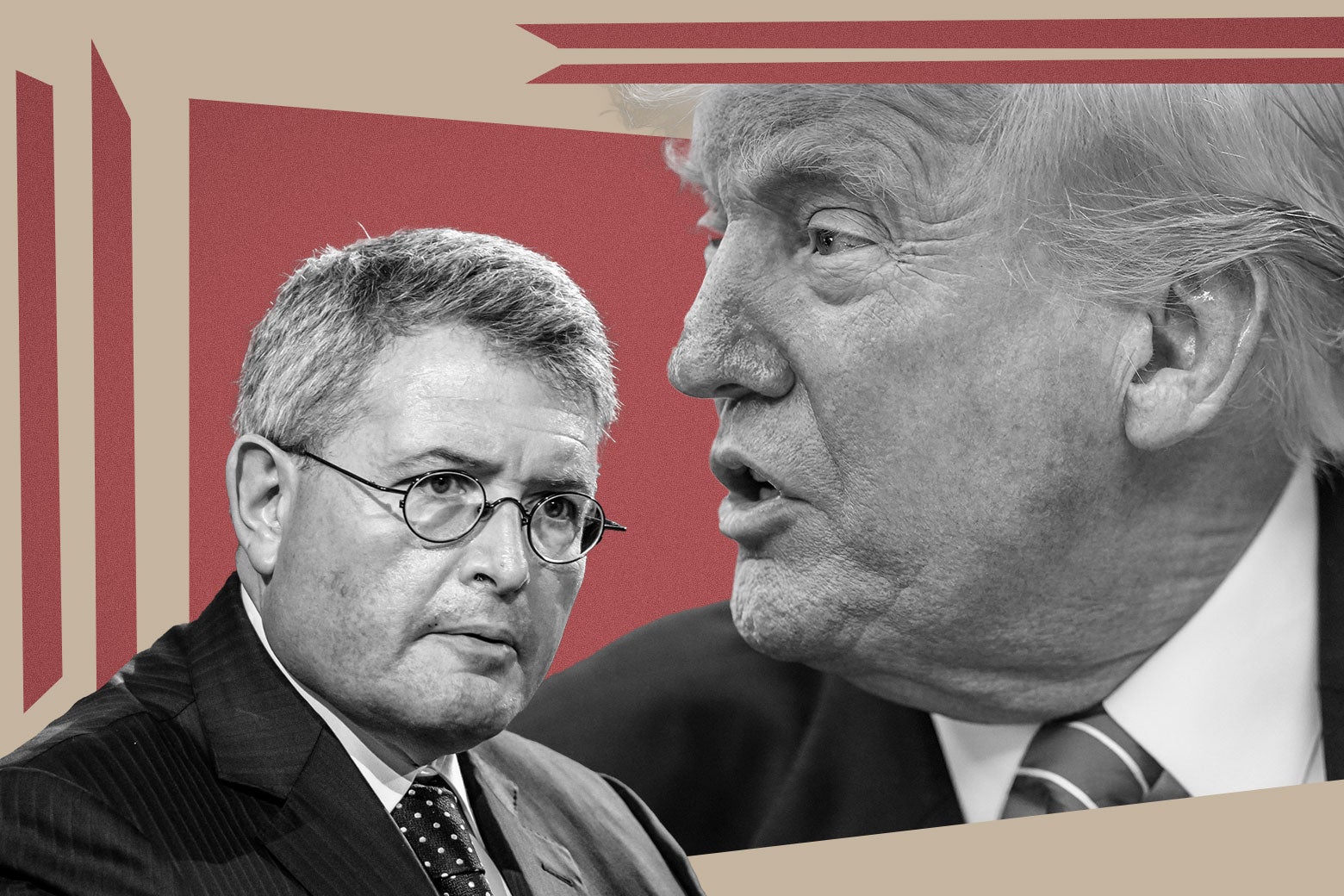

Last week, President Donald Trump took many in the legal world by surprise when he attacked the chief architect of his first-term judicial nomination agenda, Leonard Leo, as a “sleazebag” who “probably hates America.” The tone was distinctly Trumpian, but the target was a bit of a shock. Back in 2016, Leo gave the new president-elect a slate of 21 Supreme Court candidates, all “Federalist people.” Selection of the 234 judges appointed in Trump’s first term was then “in-sourced” to the Federalist Society, according to former White House counsel Don McGahn.

Trump’s outburst marks a dramatic jolt to the relationship between Trump and the Federalist Society, as well as for the conservative bench at large. It is not likely a rupture, but rather a signal that the society must bend the knee—as all others seeking federal benevolence must do—to keep its prized place. Like the traditional Republican elites Trump has left in the dust, the society needs to find a place among the ornaments on the presidential mantel, or else be cast into the dust.

Founded in 1982, the Federalist Society has long exercised subtle, behind-the-scenes influence on Republican judicial picks. Its official line emphasizing “originalism” and “textualism” belies how predictably its picks track Republican views on regulation, presidential power, and religion. Such priorities reflect Leo’s enduring closeness to traditional Republican elites such as Sen. Mitch McConnell.

In 2016, it was Trump who benefited from the Federalist Society stamp of approval. A staggering 77 percent of Republican voters that year reported that Supreme Court appointments were “very important” to them. The Federalist Society’s process for credentialing nominees as clearly conservative helped Trump ostentatiously meet his campaign promise to appoint judges who would please these voters.

And the bench he built didn’t disappoint. Since 2020, a Supreme Court with three Trump appointees has advanced Republican priorities on affirmative action, abortion, and religious liberties. Perhaps even more significant have been its dramatic curbs on federal regulation in the form of “the major questions doctrine” and end to so-called Chevron deference, not to mention its stratospheric advancement of executive power in Trump v. U.S.

In 2025, the judicial and political terrain look different. Thanks in part to rulings like Trump v. U.S., the president is no longer the supplicant. Traditional Republican elites are now “terrified” of an Elon Musk–funded primary instigated by the president. He is no longer in thrall to policy and personnel choices. Sen. McConnell, for example, has voted against numerous Trump Cabinet nominations—not, to be sure, with any effect. Other stalwarts within the party have bucked against the president’s tariffs—again to no palpable result.

It is thus not simply that the president and Republican elites have split on policy: The brute force of Trump’s political power means that, for now at least, the president has the whip hand.

This same pivot is playing out in the president’s relation to the courts. For one thing, an administration that doesn’t know the meaning of basic constitutional rights such as habeas corpus—even as it violates that right—is unlikely to be one that places great weight on fidelity to originalist constitutional values. For another, a White House that treats mandatory federal spending as a cudgel against ideological foes will surely view judicial nominations in the same transactional way—just another perk with which to punish enemies or reward friends.

Today, courts rank among the hostile. Remember that the first Trump administration received bruising losses in cases concerning Deferred Action for Child Arrivals and a census question on citizenship. Even though Trump himself had appointed a full quarter of that bench by the end of his first term, the administration has faced a “stunning” tally of court losses in recent weeks.

Worse, decisions that once were Republican trophies wrought from an archconservative Supreme Court are now albatrosses weighing the Trump II project down. Take last month’s ruling invalidating the April 2 tariffs. This unanimous three-judge ruling—joined by one Trump appointee—hinged upon the “major questions doctrine” that is a cornerstone of the Roberts court’s deregulatory policy agenda. Trump is here being bitten by the beast he bred.

And unlike traditional Republican elites, Trump now is not pursuing a policy agenda in which the federal courts could be useful aides. The White House has shown that it believes itself capable of redefining citizenship, geography, and even biology by fiat. It hardly needs hand-holding by black-robed jurists. Like Congress, the hope is that the courts can also be relegated to mere accoutrement.

In attacking Leo, Trump is thus simply making plain this new alignment of power. Like other parts of the Republican establishment, he is saying, Leo and the Federalist Society have a role to play only if they are unswervingly loyal not to the Constitution, but to Trump’s own project.

Moreover, the president has made it clear what he demands from judges: As his post on Leo explained, he believes that the only reason a judge would rule against his policies is bad faith. So what he wants are men—like his recent U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit nominee Emil Bove—of dubious ethics but unswerving and uncaveated loyalty to the president.

It will now be up to the Federalist Society to decide whether they will bend the knee, following the example of other Republican elites, to say nothing of law firms and universities. While it might seem that fealty to “original public meaning” and to history would make this an insuperably difficult ask, it is a mistake to think that the legal conservative movement cannot adapt.

Several prominent judges appointed by Trump, for example, have already pivoted from “originalism” to a vague “common good” conservativism. (If this sounds harmless, just take a second to reflect on who is implicitly getting to define the common good.) Even those who want to keep their originalist credentials are likely to find new play of the joints of their “theory.” Witness, for example, the flip-flops of some judges and scholars on the long-settled question of birthright citizenship, including at least one prominent conservative appellate judge said to be auditioning for a Trump appointment to the Supreme Court.

Even on the ground, the young men (and a few women) who swell the Federalist Society’s ranks in law schools are reportedly champing at the bit to embrace the Trumpian project.

So there’s no reason to think the Federalist Society won’t take the hint. Once, the society styled itself a guardian of the original Constitution. Tomorrow, they may serve a different master as they screen candidates to serve in the judicial Praetorian Guard that this president so keenly desires.

Sign up for Slate's evening newsletter.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·