More Republicans say they trust the national news now than last year. Why?

Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

In 2016, when a man at a Trump rally was photographed wearing a shirt that said “Rope. Tree.

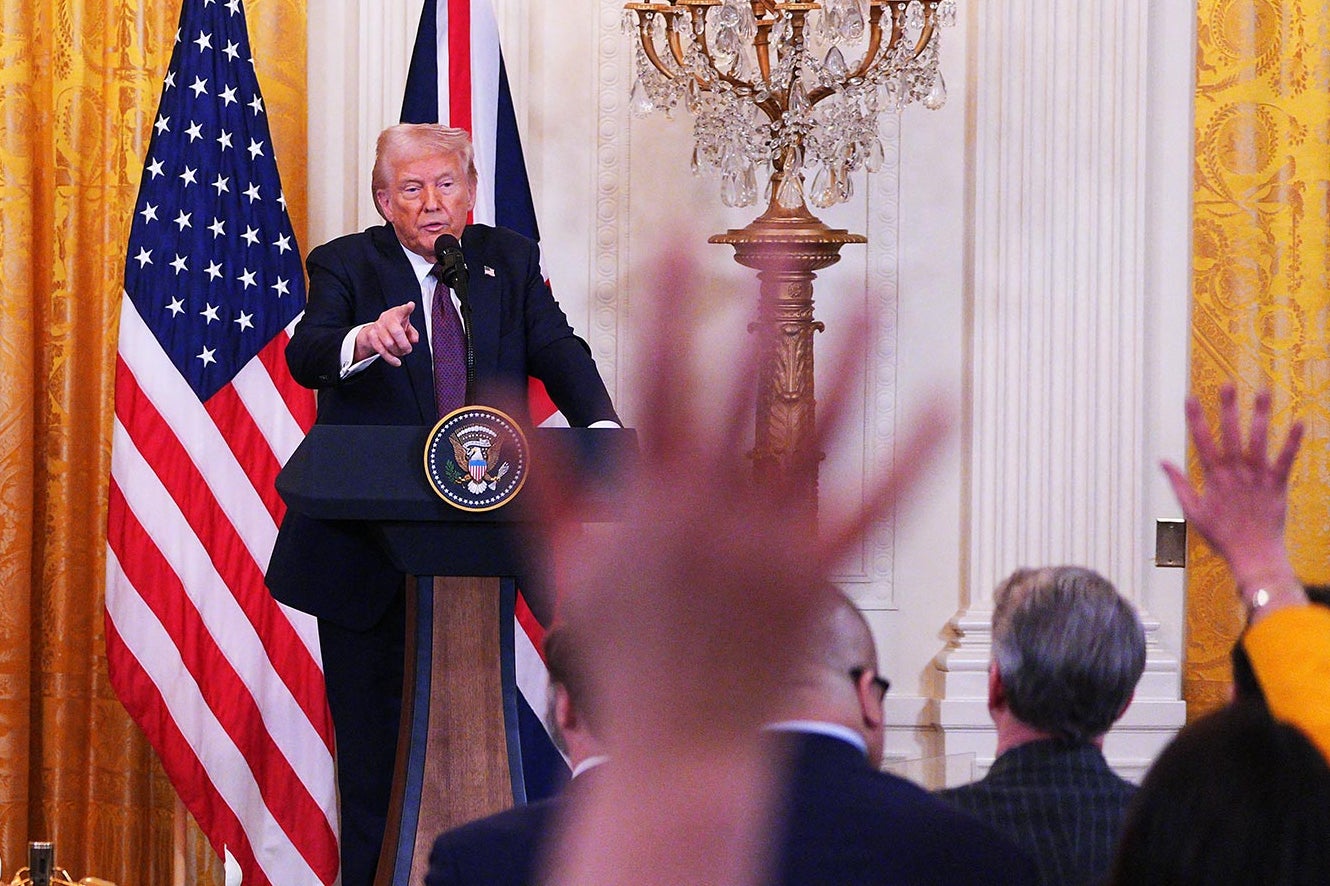

Journalist. SOME ASSEMBLY REQUIRED,” it made headlines. Back then, it was perceived as a dark sign of how then-candidate Donald Trump had, with his declarations that news media were “the enemy of the American people,” fundamentally reshaped the Republican Party’s relationship with the press.

Now, almost a decade later, Republican hostility toward mainstream news media is treated as a fact of life. The White House’s abuse of reporters is routine, and the default position of Trump supporters is one of animosity toward and distrust of the press. It’s hard to imagine this reality ever changing, given that there’s no containing so many of the factors that led here: increasingly advanced algorithms that funnel people toward insular information environments; conspiracy theorist content creators and right-wing influencers who push previously fringe belief sets vilifying traditional institutions; and, of course, the assault on press freedom from the administration.

And yet, there’s at least one sign that things might be changing. Last month, the Pew Research Center released a survey that found that in the past year, Republican trust in mainstream news media has increased. According to a survey of 9,500 Americans, about 53 percent of Republicans and Republican-leaning adults have at least some trust in the information from national news organizations. That’s a 13-point increase from last year.

It’s still a lower number than Democrat-leaning adults, which is at 81 percent in Pew’s survey. But more than half of Republican-friendly respondents answering in this way seems like a substantial amount, given the factors at play.

To understand where this sudden about-face came from, Slate reached out to Toby Hopp, a professor at the University of Colorado, Boulder, who researches trust in the news, political knowledge, and the use of alternative political media platforms. Hopp prefaced the discussion by noting that any single survey can involve statistical flukes that make it hard to form any definitive conclusions. But Pew’s survey still found a statistically notable increase in Republicans’ trust, and Hopp offered some theories that would explain how such a long-standing and seemingly irreversible trend just might be starting to turn around.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Slate: I have to admit that I was a little shocked by these Pew numbers. With the caveat that we will need more polling to affirm this finding: What’s going on here?

Toby Hopp: It’s hard to say there’s one factor that might explain this particular observation. [But] if we look just at the national media, we’ve seen organizations change how they go about interfacing with the public, particularly in the op-ed sections. There’s been a concerted effort from some of these large news organizations to bring folks in from the Republican Party. The Washington Post decided not to endorse a candidate; we’ve seen subsequent changes to the Washington Post editorial posture. A big part of what alternative media on the right does is media criticism, so when the Washington Post declined to endorse a candidate in the 2024 presidential election, it was a fairly big story on these alternative outlets. On the local level, you’ve seen actors like Sinclair purchase a large number of local news stations. And so perhaps some of these efforts, in their combined form, may have led to Republicans thinking slightly differently about the national news.

This Pew poll asked people about national news organizations, without necessarily qualifying what was meant. Now the media landscape is so fractured, with people consuming video, audio, and text from so many legacy organizations, YouTubers, podcasters, influencers—could it be that Republicans are also changing what they consider to be “national news”?

It’s an interesting question, particularly because we’ve seen real changes to who has access to the national political apparatus. The White House news corps has been reconstituted over the past four or five months to include more of what we have historically thought of as alternative or emergent media sources.

Pew’s survey didn’t necessarily find that this rise in trust from Republicans came at the expense of Democrat-leaning adults; it found that Democrats’ trust in information from national news organizations has been largely steady over the years. Are there limits to what this idea of “trust” tells us?

Trust is just one barometer of news media performance. So I’d be interested in seeing: Are we seeing changes in consumption? One of the other sides of a strategy in which you choose not to endorse a political candidate or choose to recraft an op-ed section is that this one group of people who has historically played a huge role in the financial, commercial success of your organization—you can’t expect that those folks are going to continue to consume your products in the same way that they always have.

Anecdotally, I’ve seen an increasing amount of criticism of these large news organizations coming from the left. We’ve seen a lot of criticism of the national news organizations with regard to their coverage of the conflict in Gaza. Their political coverage, since 2016, has been really criticized as being access-oriented, seeking to engage in newsgathering activities that involve getting anonymous reports or other types of things. Or it’s salacious aspects of who likes who within the White House.

It’s sometimes easy to think of the partisan split in news trust, with Republicans having less trust than Democrats, as a kind of law of the universe. Looking historically, has this always been the case?

[Through most of U.S. history] the press was outwardly and highly partisan. Then, in the ’60s and ’70s, the post-Watergate era, news organizations made a deliberate and, some would argue, commercial decision to embrace these norms of objectivity, independence, and serving the public sphere. That corresponded with a time in American politics in which we saw diminished political competition. If you combined that with the reality that the mass media was the dominant force of information distribution in society, you had this scenario—which I would argue is generally atypical in American history—in which Americans were getting their news from a limited set of sources [that they had] a great deal of trust in. So consumption habits for news looked similar across political parties.

When Trump first ran for president, he took a very different tack in which he really aggressively attacked the news. If you look at Pew’s data, you see this dramatic decrease in trust among Republicans around the 2015, 2016, 2017 mark. So this notion of partisan striations in trust in the mainstream media is both part of American political history and also a fairly new phenomenon, relative to the 50 or 60 years that preceded Trump.

Do you think this is going to be a trend that will continue? What do you think will happen with public trust in the national media?

I don’t think that we’ll return to the scenario that we saw in the ’70s, ’80s, ’90s, where the default position for most Americans was that the mainstream news was trustworthy. We exist in a high-choice media environment, [with] outlets that are defined in large part by their opposition to the mainstream news. Media criticism has been integrated into a lot of these alternative and emergent platforms. And it does seem like we exist in a general era of distrust.

But I do think, at some point, we’ll look back and say there was a bottoming-out point. I don’t think we’re going to be returning to a scenario anytime soon where 70, 75 percent of the American public is indicating a large degree of support in the national news media. But it’s not plausible to think that we’re going to continue to see a downward trend until no Republican in the U.S. has any level of trust whatsoever in the New York Times. So my prediction would be that we’re in a holding pattern. That this is the new normal.

But so much of that is dependent on what types of social and political crises are in our future. COVID obviously played a particular role for a particular type of person relative to how much they’re willing to [trust] not only the news media, but the government, health officials, so on and so forth. And there are many, including myself, who would say we’re in a moment of democratic crisis. And how the national news organizations choose to react to that crisis will play a role in the trust that they’re allocated. These large news organizations should not take for granted that liberal and left-leaning citizens are going to continue to consume their products.

I think what I’m specifically interested in is not so much the business model part as the idea of a shared sense of reality. And I think what I’m taking away from this discussion is that we are not seeing a trend in which Republican readers are suddenly, now, accepting what the Washington Post fact-checker is telling them about the COVID vaccine, for example. Am I wrong? Is there any part of this finding that indicates Americans are now more willing to believe reporting that cuts against their partisan ideas?

I think one way we might look at it is there may be a change in the Republican cohort in this country related to how angry they are at the mainstream news media. Not necessarily that they’re using it more or relying upon it more to make decisions, but that the outpouring of anger that we saw, particularly after the 2016 election, is waning or receding.

So, in a generic sense, more Republicans may have indicated that they have some level of trust in the mainstream news media. Are other behaviors changing? Are they using that information more? Are they using that information to make sense of the political and social realities around them? And, honestly, I don’t think that we have any real basis to believe that that’s true.

Sign up for Slate's evening newsletter.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·