Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

The Supreme Court handed the Trump administration a major victory on Monday night, lifting a restraining order that had prevented the mass deportation of migrants to an El Salvador prison under an 18th century wartime law. By a 5–4 vote on the shadow docket, the justices crushed the migrants’ sweeping class action in D.C. and forced them to proceed with narrower suits through more hostile courts in Texas. The majority’s unsigned, thinly reasoned decision will make it significantly easier for the administration to illegally ship off innocent people to a Salvadoran prison, where all their constitutional rights—and quite possibly their lives—will be snuffed out. As Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in a staggering dissent, “we, as a nation and a court of law, should be better than this.” But in the view of five justices, it seems that we, as a nation, are not.

Monday’s order lends undeserved legitimacy to a program that has been brazenly illegal from the start. In mid-March, Donald Trump invoked the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to justify summarily deporting Venezuelan migrants to the notorious CECOT mega-prison in El Salvador. The act applies only to a “foreign nation” that conducts an “invasion or predatory incursion” into the United States during a “declared war.” Trump claimed that Tren de Aragua, a Venezuelan gang, constitutes a “foreign nation” that is “invading” U.S. territory, which is obviously untrue. Nonetheless, he immediately directed immigration officials to round up migrants, often on the basis of nonexistent evidence, and fly them to CECOT. On March 15, U.S. District Judge James Boasberg found this plot to be unlawful and ordered the government to turn around two planes carrying migrants to El Salvador. The Trump administration refused, defying Boasberg’s order, and contempt proceedings are ongoing.

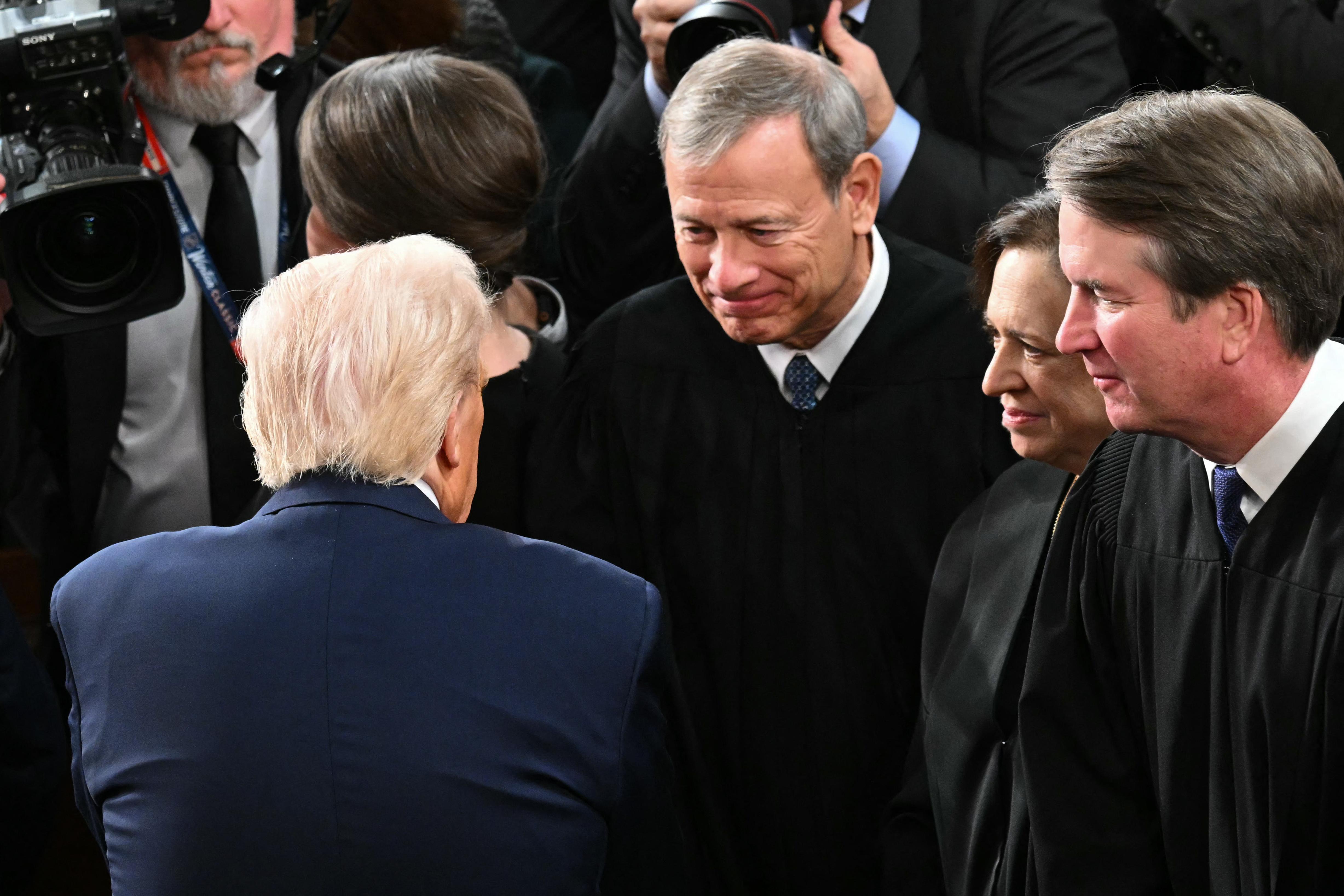

Boasberg also certified a class action lawsuit against the scheme and issued a temporary restraining order halting further removals under the Alien Enemies Act. An appeals court upheld his actions, prompting the Justice Department to ask SCOTUS for relief. Now the court, by the narrowest margin, has given the government what it asked for, clearing away Boasberg’s restraining order and blowing up the entire class action suit. Chief Justice John Roberts joined with Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, and Brett Kavanaugh to make up the five-justice majority; in a notable defection, Justice Amy Coney Barrett joined the three liberals in dissent.

The majority opinion purports to be modest, but it constitutes a painful defeat for the plaintiffs. According to the majority, the migrants cannot sue in D.C., where the president and his subordinates are planning and carrying out much of this program. Instead, they must file petitions for habeas corpus in the federal courts where they are being confined in south Texas.

This requirement will sting for two reasons. First, most federal judges in Texas are extremely conservative and are far less likely to safeguard the migrants’ rights; even if they do, the government can appeal to the MAGA-aligned, far-right U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit, which is all but certain to rule for the government. Second, the plaintiffs will probably have to file individual habeas petitions, pressing their cases one by one, since the Supreme Court has never approved “habeas class actions” (and Texas judges surely won’t do so). So the litigation will become far more laborious and time-consuming. (How they will gain access to a lawyer is another troubling question.) And in the related case of Kilmar Abrego Garcia, the Justice Department has taken the position that migrants have no rights once locked up in CECOT. So if a conservative judge rubber-stamps a deportation, and officials whisk away the migrant to El Salvador before he can appeal, he will have no further access to justice in the view of the U.S. government.

Moreover, it is also entirely unclear where migrants who have already been deported to El Salvador must now file their petitions. They had been represented by the classwide litigation in D.C. which is now defunct. But they cannot file in Texas because they’re being held in a foreign country. The Trump administration has taken the position that these individuals can’t file habeas petitions at all; they are simply stuck in CECOT indefinitely with no recourse. If migrants can only file habeas petitions where they’re detained, and these individuals are detained in another country’s prison, does that mean they cannot file any petition at all? SCOTUS does not appear to have considered this problem.

There is one silver lining to Monday’s intervention: The majority went out of its way to clarify that migrants targeted under the Alien Enemies Act do have due process rights to contest their removal. “Detainees,” the court wrote, “must receive notice after the date of this order that they are subject to removal under the Act. The notice must be afforded within a reasonable time and in such a manner as will allow them to actually seek habeas relief in the proper venue before such removal occurs.”

This is a key concession: Despite the majority’s claim that the government “agrees” migrants must receive judicial review, the Trump administration has asserted that it can deport them without due process. (That’s how it was able to whisk many off to CECOT in the first place.) Sotomayor lifted up this aspect of the decision in her dissent, noting that it means “the government cannot usher any detainees, including plaintiffs, onto planes in a shroud of secrecy, as it did on March 15, 2025” or “immediately resume removing individuals without notice.” She then issued a direct warning to the administration not to defy this unanimous holding, writing: “To the extent the Government removes even one individual without affording him notice and a meaningful opportunity to file and pursue habeas relief, it does so in direct contravention of an edict by the United States Supreme Court.” Barrett only signed on to certain portions of Sotomayor’s dissent, but it was notable that she put her name on this section.

In the rest of her dissent, Sotomayor did not disguise her contempt for the administration’s actions throughout this case. “The government’s conduct in this litigation poses an extraordinary threat to the rule of law,” she wrote. Its position is that even “United States citizens could be taken off the streets, forced onto planes, and confined to foreign prisons with no opportunity for redress if judicial review is denied unlawfully before removal. History is no stranger to such lawless regimes, but this nation’s system of laws is designed to prevent, not enable, their rise.” (Barrett, unfortunately, did not sign onto this powerful section.) Sotomayor also detailed the administration’s evident defiance of Boasberg’s order, and wondered why the majority should rush to grant relief to the government after its egregious behavior in the courts below. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson was equally blunt in a separate dissent, drawing a comparison between Monday’s decision and the court’s notorious ruling in favor of Japanese internment in 1944’s notorious Korematsu v. U.S.

“At least when the court went off base in the past, it left a record so posterity could see how it went wrong,” Jackson wrote, castigating her colleagues for smuggling through their dirty work on the shadow docket. “With more and more of our most significant rulings taking place in the shadows of our emergency docket, today’s court leaves less and less of a trace. But make no mistake: We are just as wrong now as we have been in the past, with similarly devastating consequences. It just seems we are now less willing to face it.”

Sotomayor persuasively argued that the majority is wrong, as a matter of law, that the plaintiffs must bring their claims through habeas in Texas. (Barrett, a stickler for legal procedure, pointedly joined this section.) But Sotomayor lobbed another, less law-based critique that raises even more ominous questions: Why should the court race to “reward” the government with this victory given its lawless and contemptuous conduct from the start of this scheme? Trump himself said that Boasberg should be impeached over his order, drawing a rare rebuke from Roberts himself. Now, just a few weeks later, Roberts has overruled Boasberg, in a move that Trump will view as sweet vindication.

The majority seems to be affording the president a strong presumption of regulatory—assuming good faith and respect for constitutional boundaries. But everything this administration has done since Jan. 20 rebuts that presumption (a reality that may be dawning on Barrett, but apparently not Roberts or Brett Kavanaugh). As Boasberg has shown, and Sotomayor noted, the president invoked the Alien Enemies Act in secret so it could hustle migrants overseas before courts could intervene. Why should he now receive this extraordinary, undeserved assistance to continue operating what is so obviously an unlawful program, with a pinky promise that he’ll afford due process this time to those ensnared on the thinnest of pretenses? Roberts’ decision to bail Trump out is a deeply ominous sign that the chief justice wants to rein in lower courts standing in the way of the MAGA agenda. If he does, it won’t just be Venezuelan migrants who pay the price.

Sign up for Slate’s evening newsletter.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·