Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

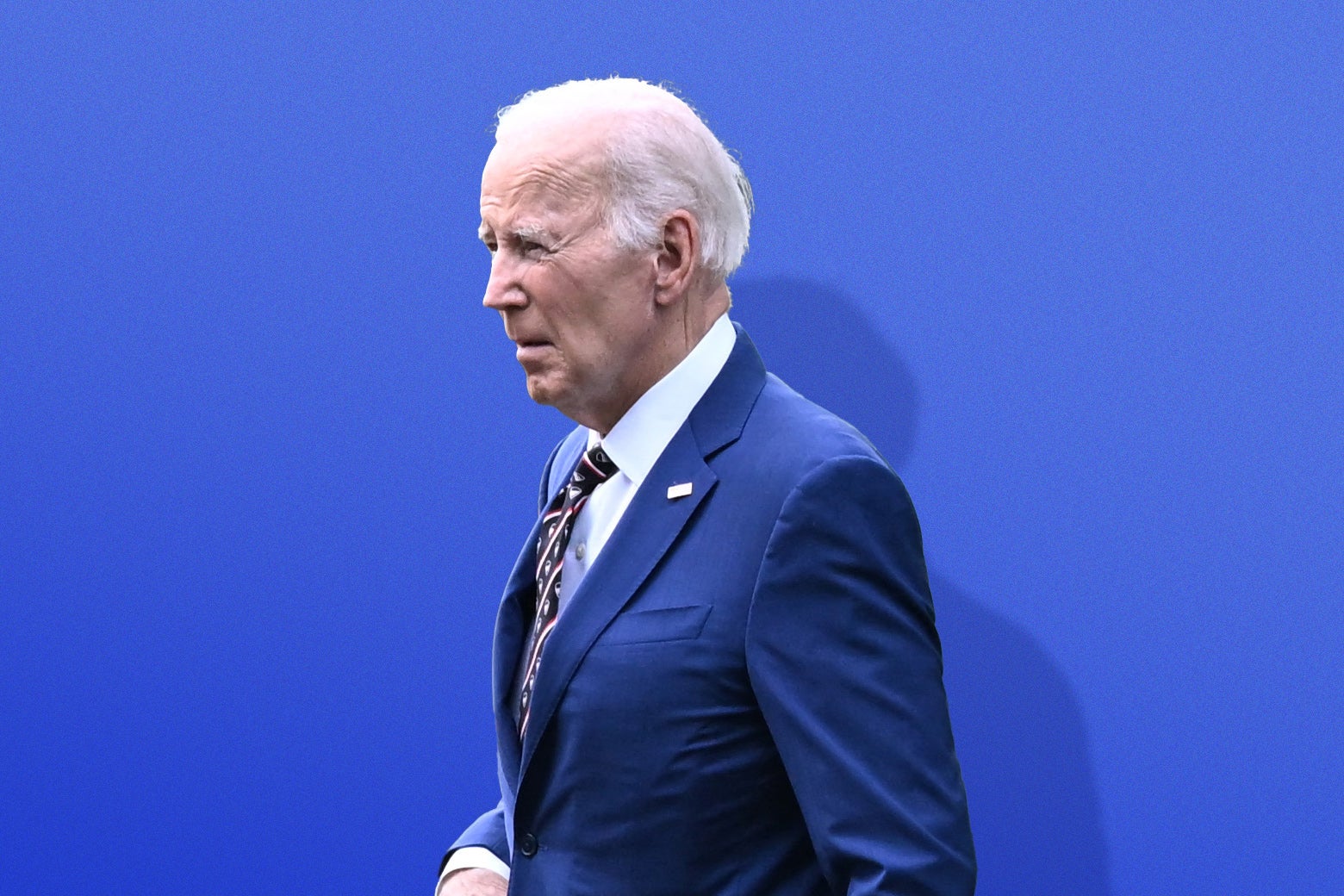

There’s one vignette in Jake Tapper and Alex Thompson’s Original Sin, the thoroughly marketed new book detailing ex-President Joe Biden’s aborted reelection bid amid his physical and mental decline, that’s unlike much of the rest.

It describes a White House event on June 18, 2024, in which the Biden administration softened its immigration policy a touch, just a couple of weeks after a sharp crackdown on asylum claims. Colorado Sen. Michael Bennet was at the event, and in Tapper and Thompson’s paraphrasing, it made him consider “what Biden’s age likely meant when it came to the issue of immigration.”

“He’d never felt as if the White House had a coherent policy,” they write. “It seemed like there were two competing sides of the debate within the administration … but no one had publicly articulated the president’s view on the matter.” Bennet “had come to believe that Biden’s inability to mediate between the people in his administration with different political viewpoints had led to an incoherent overall position on the issue.

“It actually mattered,” Bennet felt, “whether there was an elected official—elected by the American people—who could navigate and articulate disputes.”

Although most of the book focuses on the efforts of longtime Biden aides and family members to “cover up” the former president’s decline to protect his viability as a candidate for reelection, this anecdote captures what is still a largely unexplored topic: What effect did this decline have on Biden’s ability to govern?

I’m not the first reader to have been struck by the passage—and by the fact that a senator of the president’s party was left guessing, just like everyone else. The lack of access to the president in the last couple of years of his term, as the book reports thoroughly, ensured that all anyone could do was guess. Cabinet meetings, or individual meetings with Cabinet officials, slowed to a trickle; teleprompters and cue cards were necessary for the president in even some closed-press gatherings. It was a small group of people who’d worked with Biden for decades—the “Politburo”—who met with him on any sort of regular basis. How many presidential-level decisions were made in those rooms, and how were they made?

The book made me recall a piece I’d written in mid-2022 about the “two-weeks-late presidency,” in the wake of Biden’s unhurried reaction to the Dobbs ruling, which eliminated the right to an abortion, and his recurring pattern of “fumbling about for a spell before he awakens to the fire.” The administration was, even then, often a reactive one that needed a few taps on the shoulder before recognizing a problem. One notable exception was on an issue Biden cared about: his management and coordination of NATO allies before and immediately after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. That remains Biden’s most assertive moment from his presidency.

Orderly management and timely decisionmaking were never going to be a strength of a Biden presidency, whether he were 80 years old or 50. Anyone who saw him, even in his prime, offer to take “a couple of questions”—only to still be going, two hours later, as his staff was neck deep in cleanup statements—understands that.

But Original Sin shows how these problems only worsened in the final years of Biden’s presidency. His energies were limited enough that devoting attention to the issue that most appealed to him—still Ukraine—left little capacity for much else. Ahead of the infamous June 2024 debate, Biden’s former chief of staff Ron Klain felt the president “had spent more time talking to European parliamentarians than American ones; he knew a lot more about what was going on in Europe than about what was going on in America.”

Did a regularly fatigued and cloistered Biden allow internal debates to linger too long when he needed to step in? What decisions were withheld from him that might have been brought to a more vigorous president, and how were these decisions being made instead? Original Sin doesn’t set out to answer these questions. It does highlight the lack of answers we have to them.

As the presidency went on, decisions that would once have been two weeks late started coming months late, if they arrived at all. It took until June of a presidential election year for Biden to recognize the festering political wound of his immigration policy and take executive action to stanch the flow at the border. The administration’s plans for resolving the Israel–Hamas war were clear to no one, and pleased no one. Even on the issue nearest to his heart—the defense of Ukraine—the administration was trapped between a growing GOP base that wanted to drop involvement altogether and Ukraine supporters of all persuasions who felt the administration was taking it too cautiously. And the defining decision of them all—to drop out of the race due to loss of confidence from the American public—came a year and a half too late.

There have been endless debates since the election about whether it was Biden’s decline or Biden’s governing missteps that did Democrats in. The short answer is that it was both. But what’s yet to be understood is how much the former led to the latter.

Sign up for Slate's evening newsletter.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·