There are books, and there are books. Why we read and what we read matters. There are some books with titles like Anna Karenina, Invisible Man, Walden, Steppenwolf, books that are spoken of as “must reads.” I always question why? Why should we read them? What will the value be for me? Of course I understand they will broaden my mind and probably introduce me to sentences longer than most emails.

But beyond the resume-padding or the vague promise of sophistication, some of these books hit a nerve. They don’t just educate; they irritate. They challenge your assumptions, your habits, your sense of who you are. They’re uncomfortable. And that’s precisely the point.

Nobel Laureates are famous for reading from a wide range of genres. For instance, Peter C. Doherty, who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1996, stated that he would “spend a great deal of time reading anything and everything.” Another Nobel Prize winner, in Physics (2005), Roy J. Glauber, indicated: “My first salvation was reading. I visited the local public library regularly and began reading the great adventure stories of Jules Verne, Alexander Dumas and Walter Scott.”

Book lists of ‘must-reads’ have never appealed to me. I tend to reach for the obscure, the out-of-print, the books with cracked spines and questionable theses, those such as Stubborn Attachments by Tyler Cowen. A few years ago I read Where Troy Once Stood, a book whose central claim is that the Trojan War took place not in Anatolia, but in England. It's far from the canon, but it was bold and meticulously argued. It made me think, and not just about Homer or geography, but about the value of contrarian voices and what it means to question what ‘everyone knows.’ That kind of reading, difficult, sometimes a little mad, is not so different from tackling the books on the Mensa list. Both ask you to engage, not skim. To stay with the argument, even if it leads somewhere strange.

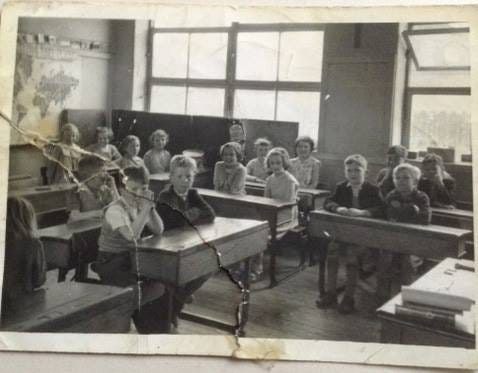

One book list I am intrigued about is the Mensa Excellence in Reading List for grades 9–12, which is not a reading list I would have encountered at that age. I was blessed to have a great literature teacher, Miss Curran, who had also taught my mother at the same junior school some 25 years, or so, earlier. (I later found out her first name was Maisie. Maisie Curran, what a wonderful literary name!)

Miss Curran’s class.

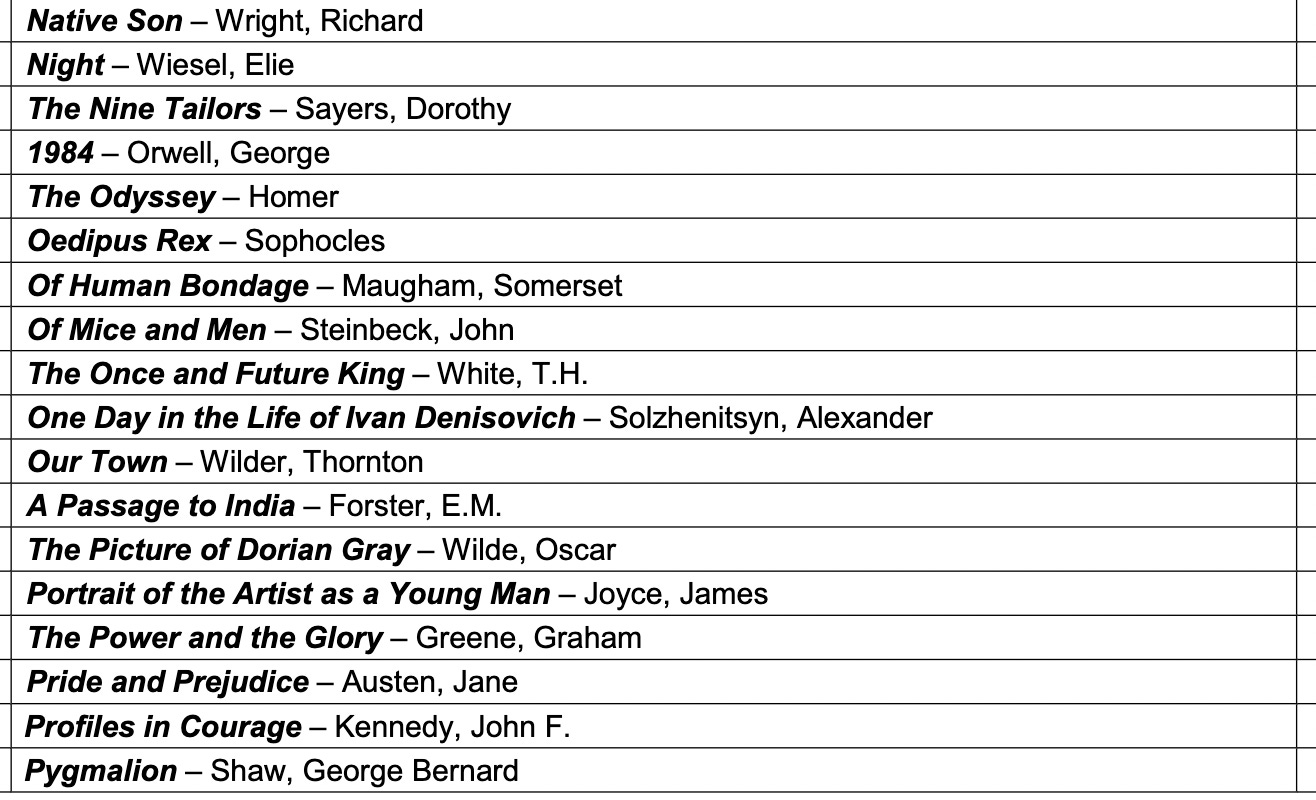

The Mensa list reads like a school assignment, but it is filled with cultural literacy, these books are existential quicksand. You don’t finish these books; you get overtaken by them and they stay with you through your life, planted deep in your psyche, isn't that what a good book should do?

But then I think, why should a high schooler, someone juggling hormones, history exams, and TikTok algorithms, wade through The Divine Comedy or The Magic Mountain? Not because they’ll automatically avoid TikTok or any other distraction, but because they’ll have practiced a different kind of attention, the kind that stretches across chapters, through difficult sentences, and into ideas that don’t resolve neatly.

Because the point isn’t just to prepare them for college and the latest meme. It’s to prepare them for contradiction, for ambiguity, for boredom that eventually gives way to revelation. I realize that Mensa-level reading isn’t about elitism; it’s about stamina. About learning to sit with a thing you don’t yet understand, and may not even like, and figuring out why it matters anyway. These are not comfort reads. They’re early warnings. Training grounds for the inner life.

I’ve read a good chunk. These books don’t give you a tidy map; they ask you to draw your own. The Aeneid? Read it while pretending to understand Latin roots. Brave New World? It left me with that quiet discomfort that lingers when you realize pleasure, when engineered and prescribed, becomes a form of control. Huxley didn’t bother with tyrants; he gave us distractions and indulgence and asked us to call that freedom. Rabbit, Run? It was claustrophobic in its honesty. Updike forces you to sit with a man who doesn’t know what he wants, only what he wants to run from. It's not redemption he's after, it’s escape, and the book doesn't flinch from the consequences.

The Magic Mountain tested my patience, hundreds of pages of fevered introspection and long conversations about death, time, and the illusions of progress. But in the long silences between monologues, it asked unsettling questions: Is health ever neutral? Or is it always shaped by the culture that defines it? Mann's sanatorium isn’t just a setting, it led me to reconsider how many of my convictions were just borrowed and I’d never bothered to examine.

Steppenwolf was no easier. Hesse gives you no comfort, no resolution, only a fragmented man caught in a maze of selves, each one more conflicted and unstable than the last. I didn’t enjoy reading it. That’s not the point. The point was that it left me with the uneasy feeling that identity, especially the tidy, cohesive kind we try to present to the world, is always a fiction under strain. It asked me to live with that discomfort instead of solving it.

The Trial was no kinder. I read it in a week and spent the next one looking over my shoulder. Kafka doesn’t need monsters; bureaucracy is enough. The book made me paranoid, not about some future dystopia, but about the systems we already live inside. Maybe what makes the list quietly brilliant, it isn’t built for satisfaction. It’s designed for friction.

You don’t breeze through Crime and Punishment without wondering, uncomfortably, how much Raskolnikov you might have in you. You don’t read All the King’s Men and come away thinking politics is a clean business. These books drag you into long conversations you didn’t agree to have.

Take All Quiet on the Western Front, it reveals in the deepest essence of what war looks like underneath. Or The Crucible, where hysteria runs on the fuel of cowardice dressed as righteousness. They teach ambiguity, not as an academic concept, but as a lived reality. They deal in contradiction, in things that are simultaneously right and wrong, or neither. They force you to sit with questions that don’t resolve, and answers that shift depending on who's asking.

Some of the best ones are short and mean. The Stranger, for instance, punches you in the chest and walks off without apology. Night is barely 100 pages but heavier than most academic textbooks I’ve owned. Then there’s I, Claudius, which is history’s version of reality TV, if reality TV were written by a paranoid genius with a gift for spite.

Many such as Jane Eyre, Their Eyes Were Watching God, Pride and Prejudice, they are not just love stories. They are revolutions in autonomy and self-definition, waged in a world that often mistook control for care and silence for virtue. They don’t beg for space in your mind, they seize it. These are not tales of longing. They’re lessons in endurance, in identity carved out under pressure.

Some titles, like The Age of Innocence or Silas Marner, appear deceptively gentle at first glance, yet they carry subversive truths beneath their period costumes. Edith Wharton threads a critique of societal constraint through every ballroom, and George Eliot slips class struggle into the quiet life of a weaver. Then there’s Things Fall Apart, which doesn’t whisper, it shouts, a colonial reckoning told not through thesis but through heartbreak.

Moby-Dick might seem like overkill, until you read it and realize it’s not about a whale. It’s about obsession, and how quickly the sublime turns into the monstrous when ego takes the helm. The Sound and the Fury throws you headfirst into disorientation, and you have to learn to read it as you go, like learning a new dialect of grief.

Don Quixote mocks romanticism while secretly mourning it. The Good Earth teaches humility in the language of land and toil. And A Doll’s House? It ends with a door slam that still echoes through modern conversations about agency.

The list doesn’t coddle, like the American mind has become. It includes 1984 and The Fountainhead. It pairs The Great Gatsby with Native Son, knowing full well they aren’t playing in the same emotional ballpark. It’s a reminder that reading isn’t about agreement. It’s about exposure.

It took me a while to realize the point of the whole exercise of the Mensa list. It’s not to become well-read. That’s a side effect. The point is to lose your smugness. To get knocked off balance by something older, stranger, smarter than you. To stop assuming you know it all.

There are a few half-read volumes from the list that glare at me from shelves. But if these books have taught me anything, the only thing worse than ignorance is certainty. Especially the kind you don’t realize you’re carrying.

For me there is no Mensa medal at the end of the list, I read because every time I think I’ve understood what a book wanted from me, another is waiting and reminds me how much is left to learn, and how much of that learning, insight and enjoyment can still come from good books.

Stay curious

Colin

Link to the Mensa Excellence in Reading List for grades 9–12

Image from ChatGPT, the joy of reading.

Note the inkwell holes in the desks, classic!

English (US) ·

English (US) ·