By Graeme Blair, Fatma Marouf, Elora Mukherjee, and Amber Qureshi

April 09, 20255:45 AM

Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

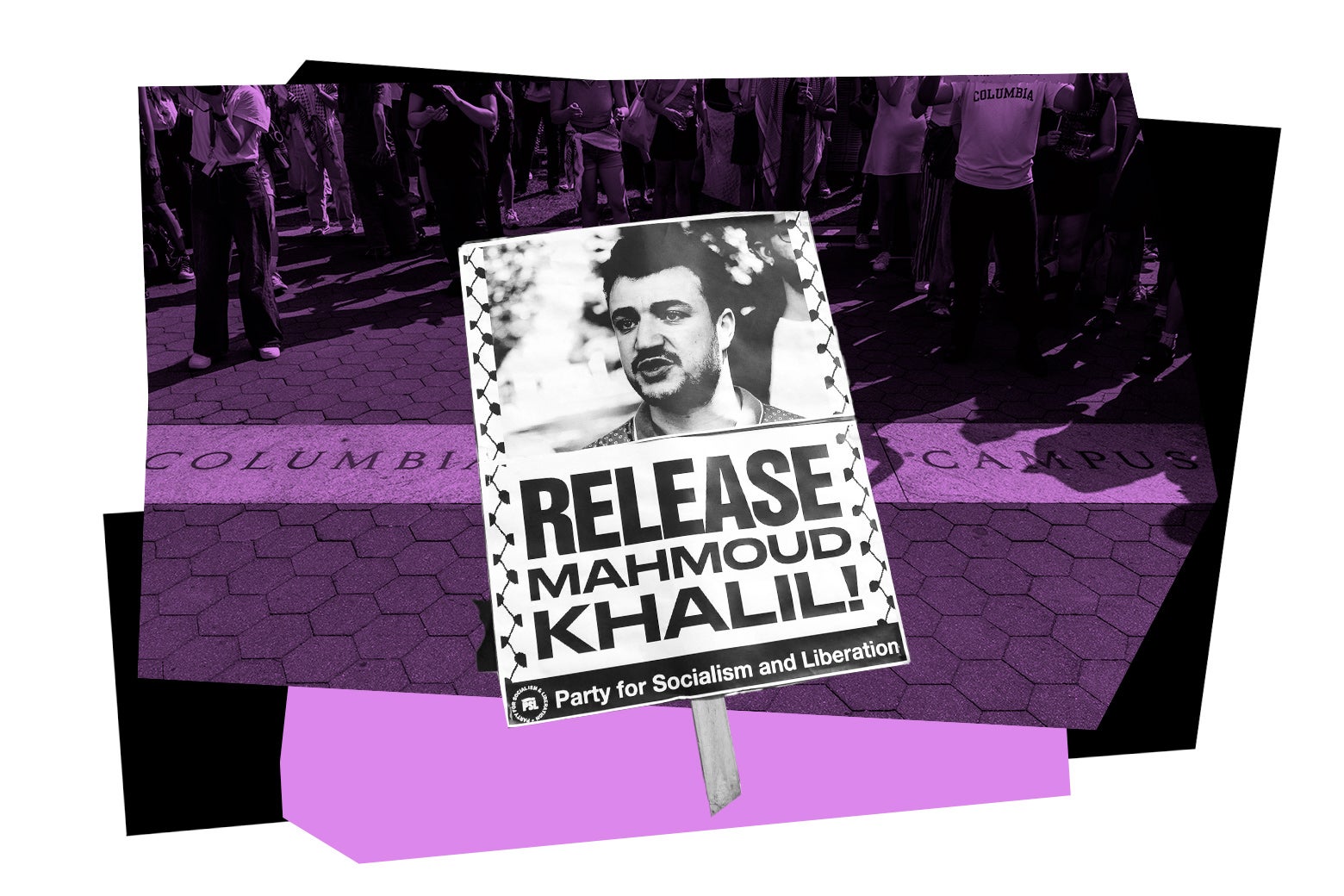

Last month, Secretary of State Marco Rubio said that he may have revoked 300 or more visas for students, visitors, and others in the United States over Palestine solidarity activism. A number of these revocations have captured national attention, such as Tufts doctoral student Rumeysa Ozturk, whose terror as she was apprehended by undercover officers was captured on film, and Columbia doctoral student Ranjani Srinivasan, who escaped to Canada before being apprehended by Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The secretary’s targets extend beyond visa holders, as he purports to revoke the lawful status of lawful permanent residents as well, with two known so far: Columbia graduate Mahmoud Khalil and Columbia undergraduate Yunseo Chung.

Hundreds of those affected by the secretary’s visa revocations related to Palestine activism remain under the radar, though some are among the larger group of revocations with various justifications made public over the past week. The numbers may only increase if Rubio is to be taken at his word: “We do it every day. Every time I find one of these lunatics, I take away their visas.” President Donald Trump has similarly vowed that Khalil’s “is the first arrest of many to come.” Given the far-reaching authority claimed by the executive branch, it’s worth trying to understand the secretary’s legal justification for revoking student visas and contextualizing the secretary’s recent decisions in the landscape of immigration law, policy, and U.S. history. Our analysis of the historical record has yielded a shocking result: According to our review, the United States has only ever used the statute it is using to justify these revocations 15 previous times.

That statute, which Rubio has been invoking as his authority for visa revocations, is 8 U.S.C. Section 1227(a)(4)(C)(i), known as the foreign policy deportability ground. This provision makes deportable any “[noncitizen] whose presence or activities in the United States the Secretary of State has reasonable ground to believe would have potentially serious adverse foreign policy consequences for the United States.” It provides one of the most sweeping grants of discretionary executive power in the Immigration and Nationality Act. The only federal district court to have considered the constitutionality of this ground held that it violates due process because it is unconstitutionally vague and deprives noncitizens of a meaningful opportunity to be heard. That decision was authored by none other than Judge Maryanne Trump Barry, the president’s late sister.

The foreign policy deportability ground was introduced into immigration law in 1990. Prior to March 2025, the use of this provision to seek an individual’s deportation was almost unprecedented in this provision’s 35-year history. Based on publicly available data we analyzed from the Executive Office for Immigration Review and published Board of Immigration Appeals decisions, out of 11.7 million cases, the federal government invoked the foreign policy deportability ground as a removal charge in only 15 cases—and only five of which involved detention throughout the proceeding. Only four individuals ever were ultimately ordered removed or deported after being charged with removability under this ground. That amounts to one person being ordered removed per decade under this provision.

What’s more, nearly all of these cases arose in the distant past, shortly after the provision was enacted. Focusing on the past 25 years until early March 2025, the EOIR data reflects that the foreign policy deportability ground has been invoked only four times, and only twice has it been the only charge alleged throughout the proceeding. Neither of those two cases involved detention throughout the immigration proceedings.

When the government invoked the foreign policy deportability ground in Khalil’s case last month—targeting a lawful permanent resident for speech protected by the First Amendment—that action appears to be unprecedented in the history of this provision and in the history of the United States. At a minimum, the government’s assertion of authority was extraordinary—indeed, vanishingly rare.

Who was targeted with the foreign policy deportability ground prior to March 2025? Publicly available data shows that these individuals hailed from around the world: Germany, Haiti, Iran, Kazakhstan, Mexico, Pakistan, the Philippines, Saudi Arabia, Slovakia, Thailand, and Yugoslavia. While information about most of these individuals is not publicly available, two publicly reported cases shed some light on how the government has invoked the foreign policy deportability ground in the past.

On Jan. 5, 1995, then–Secretary of State Warren Christopher invoked the foreign policy deportability ground against Mohammad Khalifah, a Saudi national, about 38 years old, who had entered the United States on a visitor visa the prior month. The State Department revoked his visa two weeks later and immigration authorities detained him, alleging that Khalifah had engaged in terrorist activity in Jordan. An indictment against him charged him with conspiracy to commit terrorist acts in Jordan, and he had been sentenced to death in absentia there. When Khalifah sought to be released on bond in a U.S. immigration court, the federal government presented correspondence from Christopher invoking the foreign policy deportability ground as well as evidence from high-ranking U.S. and Jordanian officials detailing his role in terrorist activities. Unsurprisingly, the immigration judge then denied Khalifah’s bond request, a decision affirmed by the Board of Immigration Appeals.

Christopher later invoked the foreign policy deportability ground on Oct. 2, 1995, against Mario Ruiz Massieu, a Mexican citizen and member of one of Mexico’s most influential and politically active families. Ruiz Massieu had long served as a professor in Mexico, directed the National Autonomous University of Mexico, and authored books on education, history, law, and politics. He then joined the upper echelons of Mexico’s federal government, eventually serving as deputy attorney general. During that time, his brother—an outspoken critic of the Mexican political system who had been secretary general of a major political party—was assassinated. Ruiz Massieu immediately commenced an investigation into his brother’s death and faced retaliation as a result. Ruiz Massieu then resigned from the role of deputy attorney general, wrote a book accusing the governing party of blocking an investigation into the murder of his brother, and reportedly faced kidnapping and death threats as a result. When Mexican authorities interrogated him, he and his family fled to the United States with temporary visas on March 3, 1994.

Two days later, a Mexican court charged Ruiz Massieu with intimidation, concealment, and obstruction of justice, and sought his extradition. Over the next year, the U.S. government brought four extradition proceedings against Ruiz Massieu on charges of obstruction of justice and embezzlement; each time the judge found insufficient evidence to support a finding of probable cause that he had committed the crimes. Christopher then effectively joined Mexico’s extradition request by invoking the foreign policy deportability ground, a move Judge Trump Barry described as “truly Kafkaesque.” Ruiz Massieu sued the U.S. government in an effort to block his deportation and he won in federal district court. Judge Trump Barry ruled that foreign policy deportability ground was unconstitutionally vague in violation of due process. Judge Samuel Alito, writing for the 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals, subsequently reversed that decision, holding that the district court lacked jurisdiction to hear Massieu’s claims, without reaching the constitutional questions.

What’s critical is this: As controversial as they may have been, Khalifah and Ruiz Massieu’s cases are a far cry from how the foreign policy deportability ground is being invoked today. Both cases involved individuals who had been charged with serious crimes abroad, not a student who engaged in peaceful protests.

The federal government’s invocation of the foreign policy ground may by no means be limited to noncitizens who engage in pro-Palestinian speech. The presence of Ukrainians who are critical of Russia, supporters of more security cooperation with Europe, and economists skeptical of tariffs on Mexico, Canada, and China could all suddenly be considered adverse to U.S. foreign policy interests and subject to deportation based on the unilateral determination of Rubio. This list has no end, and no meaningful limiting principles.

On campuses and in communities nationwide, students, scholars, researchers, and ordinary people are increasingly fearful of speaking freely. Even naturalized U.S. citizens and those with dual U.S. citizenship are concerned. The chilling effect of the recent arrests should worry us all, regardless of our views on the recent student protests. These arrests have the potential to reshape college campuses and American life for at least a generation, as activism is subdued in the wake of state-sanctioned disappearances and international students increasingly choose not to study in the United States. In the shadow of this chilling silence, our country loses out on the talents of highly skilled immigrants and our nation lurches closer to authoritarianism.

Sign up for Slate’s evening newsletter.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·