It’s not just a job for women.

Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

Pronatalist discourse has a preoccupation with women’s behavior. Consider the recent headlines: “White House Assesses Ways to Persuade Women to Have More Children,” “Why Musk, Vance and the Right Want Women to Have More Babies,” and “The Push for Women to Have More Children Has a Powerful Ally: Trump.” Despite pronatalism’s associations with ethnonationalist rhetoric and strange people in bonnets, the falling global birth rate is a real concern; the declining supply of young people threatens our long-term economic and social future.

Paying attention to women’s choices makes sense, because when women can access birth control, they have fewer children. For women, especially educated women, there is a high physical and economic opportunity cost to having children. Care work is societally undervalued, and parenting is not treated as the important public service that it is.

But focusing only on women ignores the untapped potential of men to improve the birth rate—not just by contributing sperm, but by helping solve those opportunity costs. I’m a fatherhood researcher who studies how men’s brains and bodies change when they become parents, and my first book, Dad Brain, will be out in spring 2026 from Flatiron Books/Macmillan. I have seen firsthand how often fathers get left out of conversations about birth and parenthood.

From a birthrate perspective, here’s the problem: There’s a lot of unpaid care work that goes into raising kids and running a household, and women don’t want to do it all.

At the level of individual families, there are two solutions to the problem:

Disempower women so that the opportunity cost of motherhood goes down and they will increase their participation in unpaid care labor due to a lack of alternatives

Encourage both men and women to participate in the paid work force but increase the domestic contributions of men so that women’s unpaid domestic labor burden is reduced

There are other solutions that involve state support, such as paying parents to do typically unpaid care labor or scaffolding the contributions of paid caregivers through child care subsidies. There are cultural solutions, like having stronger intergenerational family networks so that unpaid care is distributed across extended families and communities (rather than dumped on small nuclear family units). There are cultural messaging solutions, too, like convincing everyone that unpaid care work is noble and crucial and that we should applaud caregivers. I’m a fan of all of these solutions.

But the fact remains: Even if you have a great day care and a grandmother nearby and a country that gives medals to mothers, you still need to figure out how to handle your own household and the extra unpaid work that children bring. In my research, I’ve studied how couples navigate the transition to parenthood, and found that the division of labor often becomes a major source of stress for moms.

At the level of the family unit, the first solution (disempower women) holds sentimental appeal for conservatives. It is the solution practiced by default in many of the highest-birthrate countries, like Niger and Angola, where there are large gender pay gaps, high female teenage pregnancy, and little political power held by women.

MAGA pronatalists are pushing versions of this solution as we speak. The Heritage Foundation has argued that too much education, especially women’s education, dampens the birth rate; therefore we should defund student loan programs and get people out of graduate school. Trump’s tariff policies reflect a nostalgia for a manufacturing economy dominated by men (never mind that tariffs will not bring back good factory jobs). DOGE cuts to the civil workforce, including programs like Head Start that provide affordable child care, affect women’s employment most. Meanwhile, abortion bans and attacks on birth control will force some women to have babies that they simply do not want. At its worst extreme, the “disempower women” solution takes us into Handmaid’s Tale territory, with women stripped of autonomy and forced into breeder roles. At its purported best, it means tradwife cosplay and fewer opportunities for women.

In addition to its obvious hazards for women, disempowering women comes with an additional drawback: It will make us poorer. A common conservative line of thinking is that women have been fed a lie that climbing the corporate ladder will bring them true fulfillment. But women entered the paid workforce not because of girlboss feminism, but out of economic necessity. If we suddenly zapped back to the 1950s era of the breadwinner male, we’d be living in smaller houses (as if, in today’s market, a one-income family can afford a house at all) with fewer creature comforts, taking fewer vacations and making fewer purchases. Our cushy consumerist lifestyles could certainly afford to be scaled back, but taking women out of the workforce en masse would crush our GDP, and lead to a huge loss of talent and potential.

So: That solution isn’t good for women, and it’s not good for the country, either. The second solution is to bring men into the home instead of taking women out of the workforce. It requires men to step up and take over more of the day-to-day grind of running a household, allowing both men and women to work outside the home, and share the burden of the extra domestic labor that comes with a child. This is already starting to happen: Between 1965 and 2012, partnered fathers nearly quadrupled their daily time spent with kids. However, “quadrupled” sounds less impressive when we consider the actual numbers: from an average of 15 minutes a day to 59 minutes. At the same time, parenting has become more intensive, and so mothers have also increased their daily participation in child care. Overall, the proportions of the total unpaid housework performed by men and women has remained unequal.

Globally, women still do most of the unpaid household and child care work, even in partnerships where their earnings match or exceed their partner’s. When women and men both work full time, women do about 70 percent of the total household labor. Among wives and husbands who earn equal incomes, women spend about two hours more on housework per week and two and a half hours more on child care than their partners. Even when women outearn their husbands, they do more domestic work than their partners. The only marriages in which men tend to do more housework and child care than their spouses are marriages in which the women are the sole breadwinner.

These figures may underestimate the added mental load of planning and anticipating household needs—researching summer camps, picking a pediatrician, or tracking kids’ food and clothing preferences. The mental load runs in the background, making it harder to measure, and is rarely acknowledged or even noticed by others. My lab’s research on this component of household labor has found that it is even more gendered than physical household labor, and takes a greater toll on women’s mental health.

Gender disparities in household labor have multiple causes. Women are socialized to be more attuned to household dynamics, and to feel guilty when they’re not fully devoted to the homefront. They may enforce unreasonable household standards or engage in gatekeeping that shuts men out of parenting. Men might also malinger, feign incompetence, or simply refuse to contribute fully at home. These are complex dynamics without singular villains.

But when it comes to the birth rate, it’s likely that a meaningful slice of women evaluate the mountain of unpaid and unappreciated domestic labor that might accompany their entry into parenthood and decide to opt out.

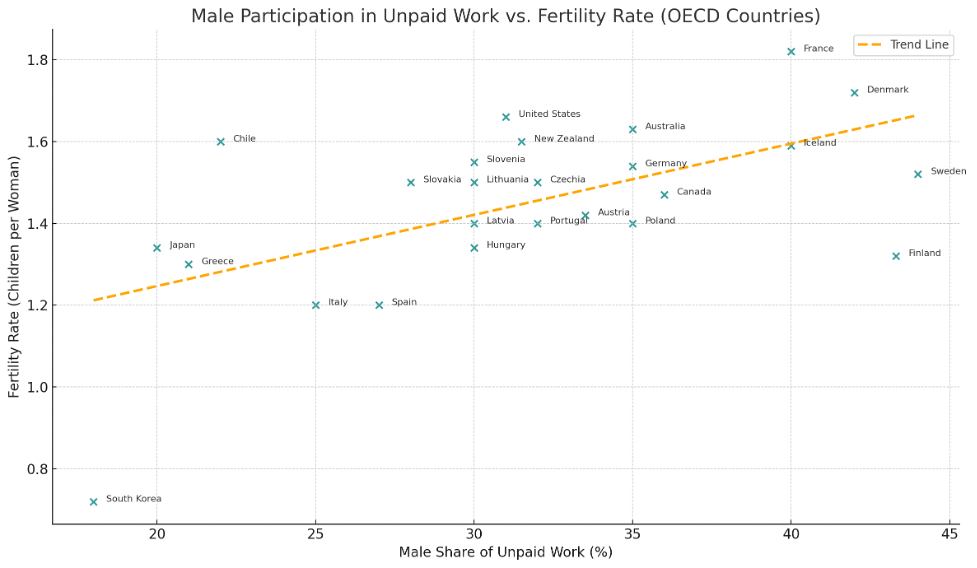

There’s real evidence that men’s household contributions track with birth rates in democratic, industrialized countries with modern economies, or what researchers call Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries. Across OECD countries, I looked at data on the average hours per week that men engaged in unpaid household labor. I then plotted those data by birth rate statistics in each country. The correlation between men’s domestic labor contributions and birth rates was quite high.

At the bottom left corner of the chart, South Korea currently has the lowest birth rate in the world, and it also has one of the lowest rates of male participation in housework among OECD countries. It has been ranked 99th out of 146 countries on gender equality. South Korean men have been called “the developed world’s least helpful husbands.” In fact, South Korean men’s reluctance to pitch in at home seems to be fueling a war between the sexes, with young women in the 4B movement eschewing marriage and motherhood.

Also on the low birth rate/ low male domestic labor end are Southern Mediterranean countries like Italy, Greece, and Spain, which tend to have more traditional gender roles than Northern Europe (although Spain has recently upped its government-provided paternity leave and seems to be undergoing a shift in gender relations). On the right-hand side of the chart, Northern European countries with generous paternity leaves, like Sweden, Finland, and Denmark, tend to have high male participation in household labor and higher-than-average birth rates for the OECD.

To sum up: If you’re a poor country or want to be a poor country, your likeliest solution to raising birth rates is to get women out of the workforce. But if you’re a wealthy country where women can access education, your best solution is actually to get men into the home.

You can do this through more generous paternity leave, especially leaves that come with special incentives or nudges like the “use it or lose it” policies found in Sweden, Finland, and other countries. You can also do this via workplace change, like having managers who encourage dads to prioritize family obligations and provide flexible scheduling options, and via culture change, like making sure dads, not just moms, get calls from their kids’ schools and pediatricians, and get welcomed into playgroups and the PTA. You can talk about men as great fathers and award medals to them, too.

So why does the “take women out of paid work” solution seem to get more traction within pronatalist discourse than “bring men into unpaid work” solution? In part, because men are leading many of the discussions, at least on the right, and they’re not keen to take on more unpaid labor at home. But there’s also a deep-seated assumption that it’s “natural” for men to do paid labor and for women to do unpaid labor.

It’s easy to challenge the first premise. The 1950s gender dynamics that attract aspiring tradwives actually reflected a brief historical blip, a time in which postwar prosperity allowed the single-breadwinner household to proliferate. For 95 percent of our species’ time on Earth, humans have worked as hunter-gatherers or subsistence farmers, and women have made meaningful economic contributions to ensure their family’s material survival. There is evidence that in traditional societies, women contributed at least half of the total calories needed by their communities. Women also worked on family farms, tending to animals or helping to process food, in family businesses, or in factories in the early days of the Industrial Revolution. To facilitate this women’s work, children have often been cared for by non-mothers or left to play with other children. There’s nothing new, or unnatural, about being a working mother.

What about men’s unpaid labor at home—is it natural to expect that men can make meaningful contributions to child care and housekeeping? Of course. As I learned when researching my book, men are very capable of adapting to parenthood and providing sensitive care, but they (just like mothers) benefit from time and practice. If we reframe parenthood as a form of skilled labor instead of an innate instinct, we can find room for both men and women to excel as parents. The same is true for chores and other forms of domestic work. There’s no rulebook that says that only women are good at meal planning or grocery shopping or laundry folding or any of the other tasks that keep a household humming. Housekeeping is a form of project management just like software engineering or building construction, and even stereotypically male skills—like spatial organization or mathematical ability—come in handy when organizing a cupboard or figuring out how many eggs are needed for a week’s worth of breakfast.

There are certainly types of domestic work that women are uniquely equipped to do because of their physical bodies (breastfeeding) or because of their social roles (for example, coordinating playdates with other mothers), but there is a large universe of domestic tasks that both sexes are perfectly capable of tackling. (And even when it comes to feedings and playdates, men can find workarounds.)

The real reason that men haven’t clamored to do more unpaid labor at home is not because of a skill deficit, but because of the value judgements that surround it. Domestic work is not valued, and men have been raised to consider their time to be valuable. And here’s my final argument about why the secret ingredient for boosting births is to get men more involved at home: When men engage more in child care and housework, societies start to see those activities as more important, and reward them more highly.

Take the Nordic countries where paternity leave is not only available but flexible, and incentivized, with “use it or lose it” programs that increase men’s willingness to take time off after birth. Those incentives do indeed successfully encourage men to take leave, and set the stage for greater paternal involvement throughout childhood. Not coincidentally, in these countries where male participation in parenting is high, there is also strong public support for caregiving and an emphasis on healthy child development. Child care is not seen as a personal favor that women do for their families, but as a responsibility shared by all adults. Male involvement may help to legitimize and elevate the perceived importance of domestic work.

Of course, some women may prefer to take on a greater share of domestic work than their partners, and some men may prefer to work outside the home. I’m not advocating that we suddenly stage a complete reversal of traditional roles or force every man to become a stay-at-home father (though some men might leap at the option). Instead, we should foster a culture that encourages men to share the domestic workload. That’s good not just for births but for marriages: Women will become more enthusiastic about partnering with those men. Women want to marry men with high fatherhood potential. That means that those of us raising young boys can focus not just on their academic or athletic skills, but their empathy, kindness, and future openness to working just as hard on a kid’s science fair project as on an important report at work. We can teach our sons to cook and encourage them to babysit. There’s a whole discourse that women only want to marry tall, beefy, high-testosterone, aggro men, but that discourse is largely propagated by male influencers and people trying to sell protein powder. If you talk to actual women, they will frequently tell you that they want to marry a good listener who will chip in at home. Many men agree: A new survey finds that men believe that taking care of his kids makes a man more masculine, and rank “family” as a higher priority than “strength.”

Not only is celebrating fatherhood good for women, for kids, and for the birth rate, it’s also good for male mental health: We know that men who are more socially connected live longer and enjoy greater well-being.

So, if we want to get the birth rate up without trashing our economy, while also solving the problem of lonely, rootless, and aimless young men, let’s champion men who are involved fathers and start focusing more of our pronatalist energy on cultivating prosocial masculinity that expands the ambitions of young men. It will be good for our kids (especially our boys), our country—and our future families.

Sign up for Slate's evening newsletter.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·