Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

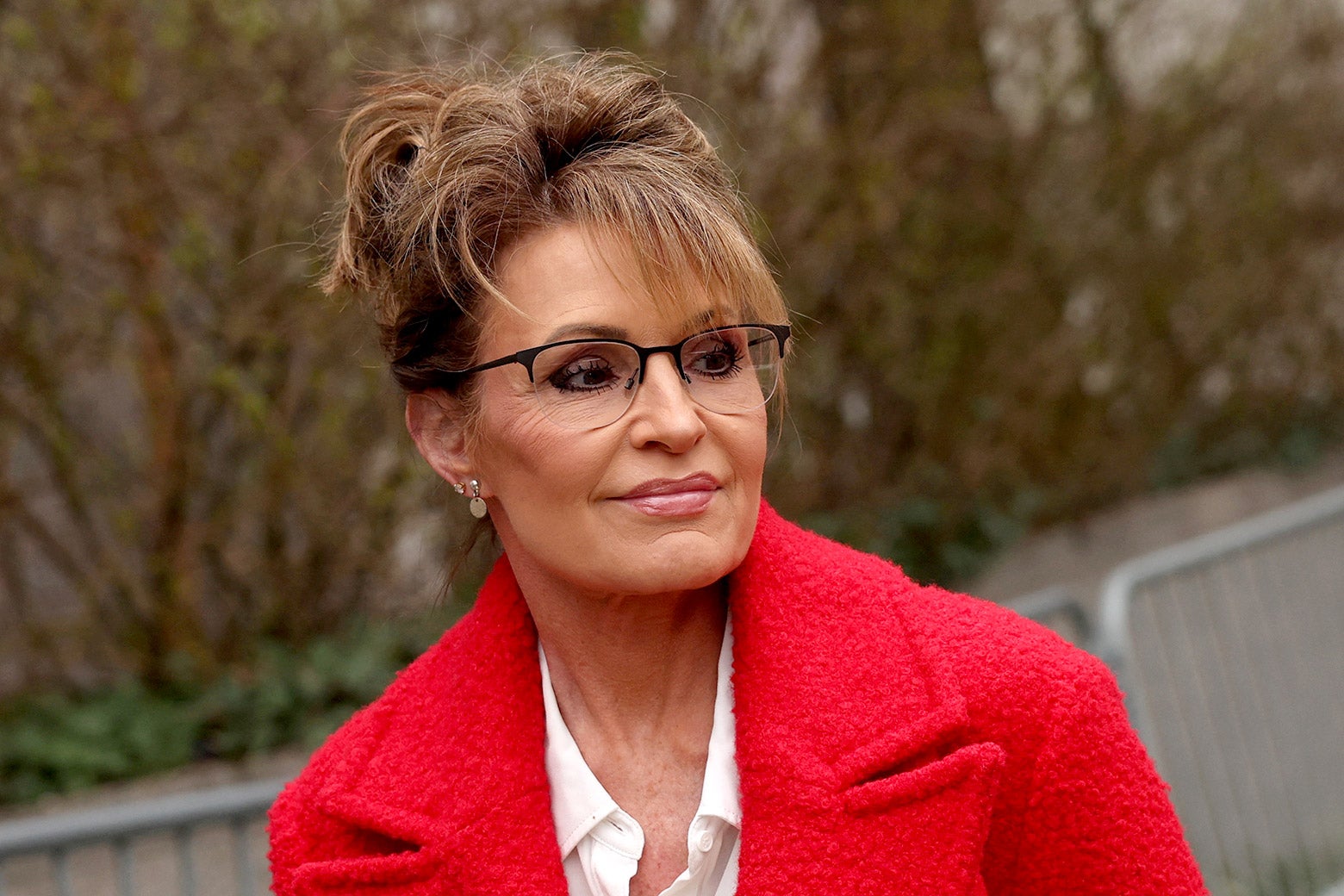

Just past 9 a.m. on Tuesday, Judge Jed Rakoff settled into the bench in his downtown Manhattan courtroom. At one table in front of him sat former Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin, swathed in a madder-red three-quarter-length coat and sandwiched between her counsel. At the table behind that sat former New York Times opinion editor James Bennet, slender and suited, with his own lawyerly retinue.

Judge Rakoff tossed off some instruction on how the standard for defamation is proven in the United States, then gave way to opening statements. And the Sarah Palin vs. the New York Times defamation suit was officially on—again.

Same plaintiff. Same defendant. Same judge. Same building. Largely the same facts. Are we really doing this again? We are. But this time, four months after Trump took office again, the case has taken on a much different sheen.

A refresher on how we got here: In 2017, the New York Times Editorial Board published a piece condemning “heated political rhetoric” in the aftermath of a mass shooting, after gunman James Hodgkinson, a left-wing activist, fired on numerous Republican congressmen and aides during baseball in Virginia, wounding Rep. Steve Scalise. The Editorial Board, in characteristic fashion, sensed an opportunity to condemn both ends of the political spectrum, and nodded back to the 2011 shooting of Democratic Rep. Gabby Giffords and the killing of six others, including a 9-year-old girl, the last incident that involved a congressperson getting shot.

Here’s where it got litigious: Of that 2011 shooting, wrote the Times, “the link to political incitement was clear. Before the shooting, Sarah Palin’s political action committee circulated a map of targeted electoral districts that put Ms. Giffords and 19 other Democrats under stylized cross hairs.”

It was an assertion, all parties admit, that was dubious. The Times quickly issued two formal corrections: The link to incitement was not clear, or plausibly fuzzy, it turned out: The shooter was not a partisan zealot but a schizophrenic. Also, it was not Democrats in the “stylized cross hairs” but their districts on a map. Unmoved by the corrections, Palin sued.

The initial case had more than a faint whiff of political opportunism. Palin was not, and still is not, seeking monetary damages. “Conservative allies had hoped to use the case to upend protections for the press stemming from a six-decades-old U.S. Supreme Court ruling in a defamation case that also involved the Times,” NPR reported. It also had a vanguard element for conservative lawfare against the reviled Fourth Estate: As Slate’s Seth Stevenson noted in his coverage at the time of the trial at the time, Charles Harder, the lead attorney for the Hulk Hogan lawsuit that led to Gawker’s demise, was there, taking fastidious notes.

It didn’t work all that well. Palin notched the rare and ignominious distinction of losing the case twice in 24 hours: Once when Judge Rakoff told the court, while the jury was deliberating, that Palin had failed to make a credible case and that he would find the Times not liable for defamation, and a second time when the jury came back a day later and unanimously ruled against her.

But as President Trump has shown, all it takes is a little help from a favorable judge or judges to fuel an unlikely comeback. A three-judge panel on the Second Circuit found that Judge Rakoff had acted out of order in announcing his position prematurely. In fact, several jurors learned of Rakoff’s ruling via push alerts on their phones before they had reached their verdict. The Second Circuit reinstated the case, finding also that certain evidence—including the fact that Bennet’s brother is Democratic Sen. Michael Bennet, and the contents of some articles published at the Atlantic during James’ tenure there—had been wrongly excluded.

So now, in 2025, we are restaging a case from 2022 about an article from 2017 referring to a shooting in 2011. This time, Judge Rakoff assured the court he had taken away the phones of all the jurors. After one lawyer asked to ensure they had also been stripped of their Apple Watches, which could receive push notifications, too, he announced that one juror had already voluntarily given up his watch, and that another was merely wearing a Fitbit, “which has access to his heartbeat, but not the internet.”

But the world where this trial is being rerun is radically different than the 2022 in which Palin initially pleaded her case.

For one thing, Trump isn’t just back, he’s back for revenge. The president sued CBS News for $20 billion over a 60 Minutes interview with his 2024 opponent Kamala Harris; he sued the Des Moines Register over an election poll that wrongly predicted him to lose Iowa. ABC News settled a lawsuit with Trump for $15 million over anchor George Stephanopoulos’ inaccurate on-air statement about the president being found civilly liable for raping writer E. Jean Carroll. The administration has also made even more dramatic incursions into First Amendment curtailments, revoking visas and deporting students over political speech criticizing Israel.

This time, the courtroom was much smaller, and there was much less public attention. I was one of just a very small number of reporters in attendance; the overflow room did not get any use.

Palin’s team kicked off with an emotional opening statement, the sort of appeal that has since been termed crybully conservativism. The New York Times “have not publicly or privately apologized to her,” lawyer Shane Vogt proclaimed. “That’s why we’re here. That’s why we’re here.” “One of the reasons this cuts so deep for her is because her own daughter was nine,” Vogt poured on. “That’s why this cuts so deep.”

The Times’ lawyers also came out strong, noting repeatedly that the writers and editors had made a mistake. But mistakes regarding public figures do not amount to the legal standard of libel, the burden of which is quite high. The “actual malice” standard means that Palin’s team will have to prove the Times published false information knowingly.

Just like so many of the high-budget remakes that have marked the 2020s, this day was not a scintillating watch. The Times writer who wrote the first draft of the editorial, Elizabeth Williamson, took the stand, and both sides pored over email chains and text threads. At one point, I saw one juror’s eyes closed. “I feel excited to go have lunch,” Judge Rakoff said when 1 p.m. rolled around.

The court was even emptier afterward. But there was a reason Palin was back here, and it was clear the Times’ lawyers had their eyes on the bigger stakes, too. That was all reinforced by what I saw on the way out.

After the hearings were concluded for the day, I approached Palin, and asked her how it felt to be right back here after three years. “It feels good to have another opportunity,” she told me affably, “to hold the press accountable.” “Justice delayed isn’t necessarily justice denied,” she added.

I followed her and her lead counsel into the lobby. Another reporter approached and introduced himself: Ben Kochman of the New York Post.

“I have a bone to pick with you,” Palin said, lightly. “You wrote I divorced my husband.” Indeed, in a piece regarding the trial published Monday for the famously conservative Post, Kochman had written: “The mom of five divorced her husband of 31 years, Todd Palin, in 2019.”

It was an inarguable factual error: It was Todd Palin who filed for divorce. Quietly, the New York Post had finessed the mistake away: Now it reads that “Todd Palin filed for divorce against her in 2019,” though the Google search cache hadn’t yet updated by the time I looked it up. The article features no correction.

But then Palin’s lawyer cracked a joke, and all of them—Palin, her legal team, and the Post reporter—shuffled into the elevator together, laughing. It wasn’t that serious, I guess.

Sign up for Slate’s evening newsletter.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·