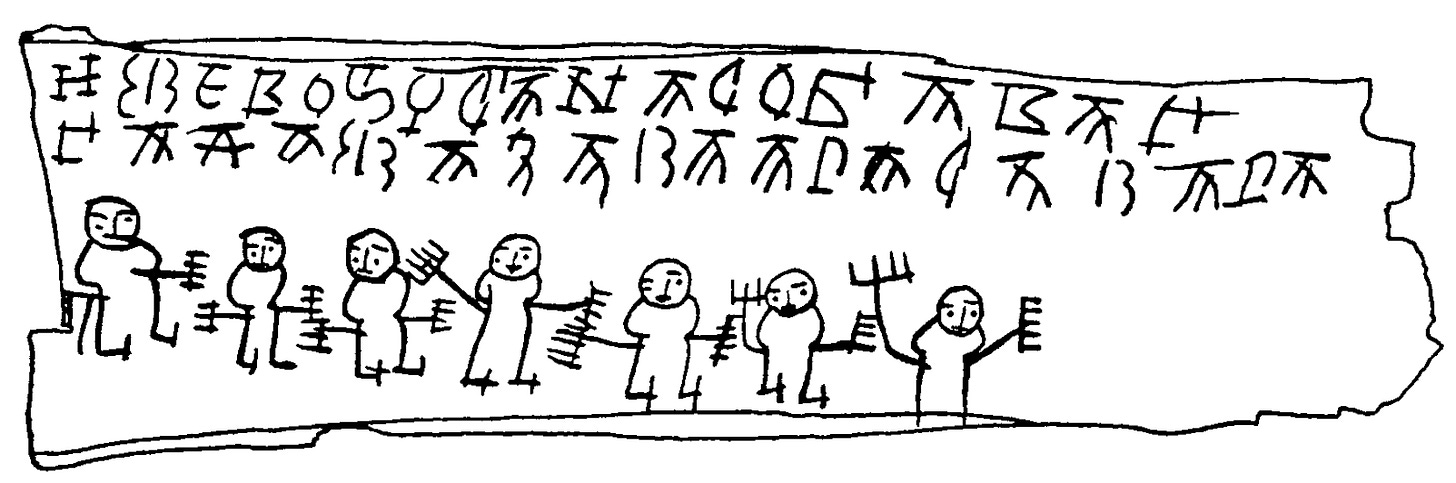

The sketches survived by chance, preserved on strips of birch bark found during Soviet archaeological excavations. They had been intended for use by school children from the medieval state of Novgorod. These children, who lived around the year 1250 CE, were meant to be learning how to read and write. But one student named Onfim used them to draw. And for this reason, Onfim has become immortal.

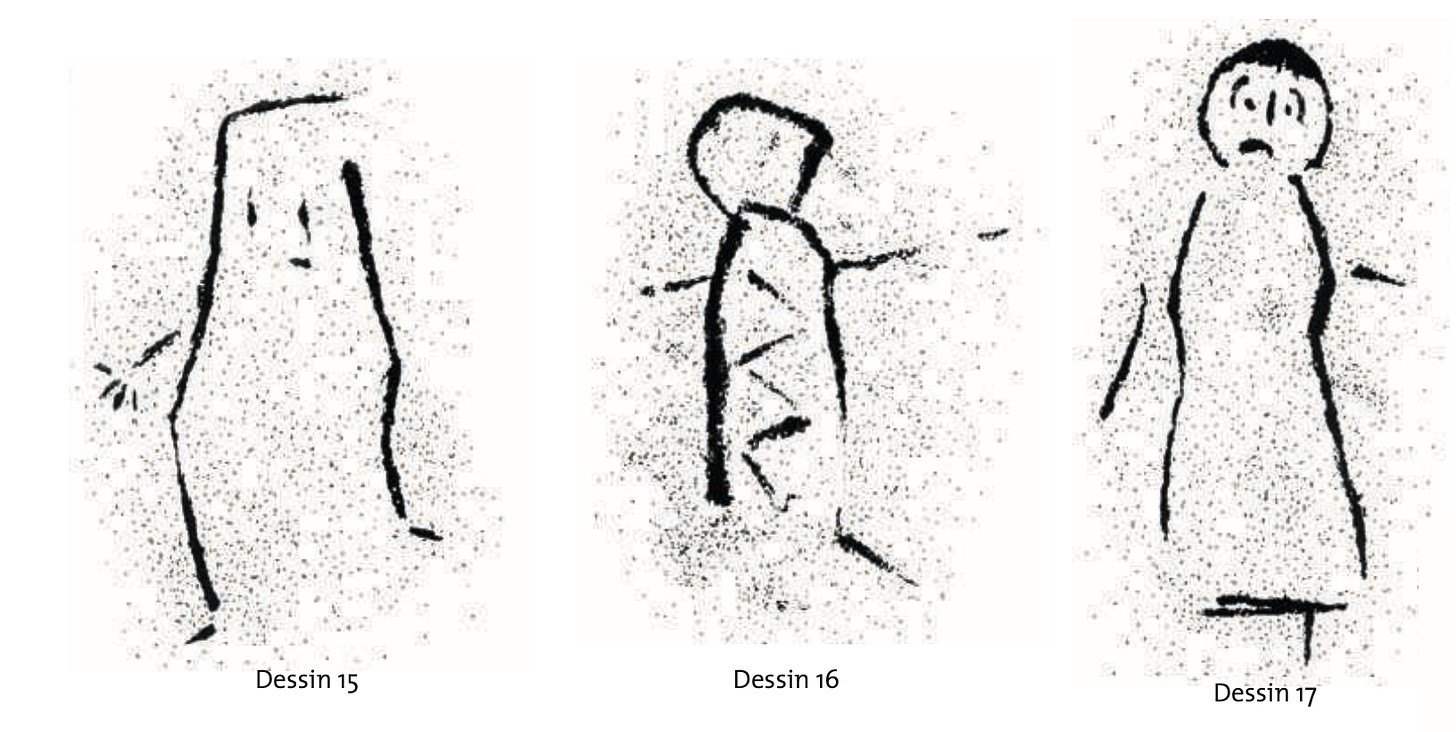

His doodles include horses and soldiers, battle scenes, self-portraits, and expressive stick figures that radiate personality across eight centuries.

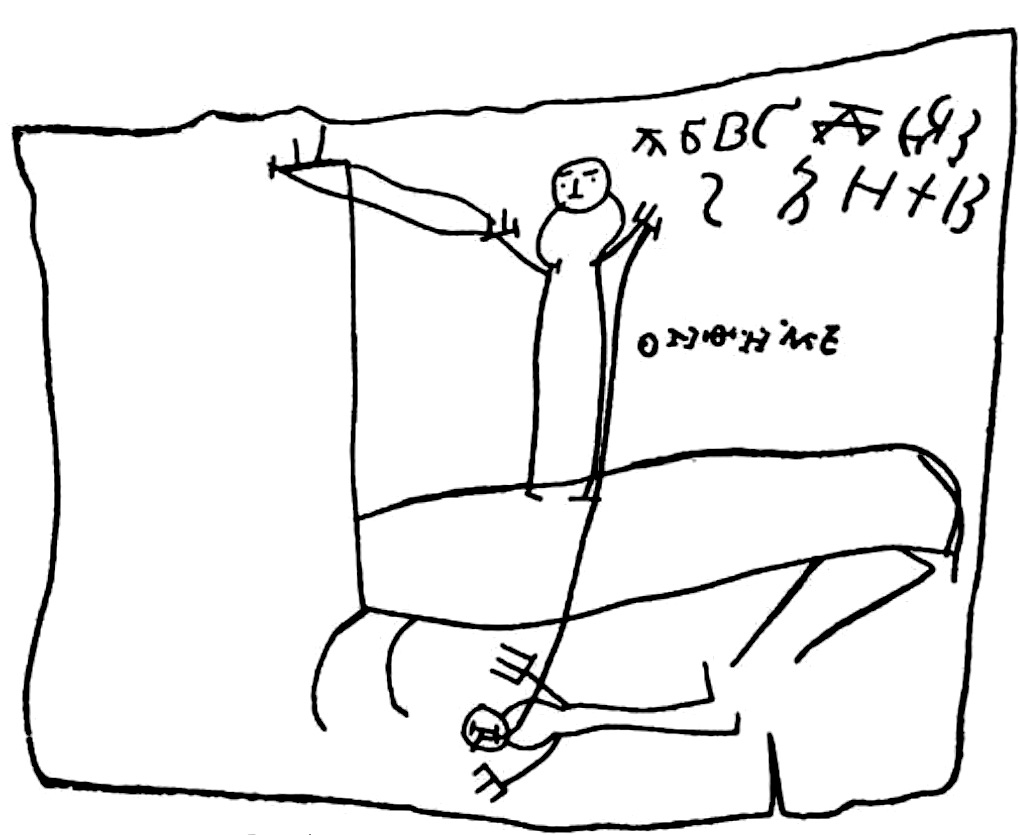

In the most famous Onfim drawing, a mighty warrior rides horseback, his lance spearing a prostrate enemy on the ground. This figure is, naturally enough, labelled “Onfim.”

To the upper right, an attempt at writing the alphabet trails off around the Cyrillic letter K.

Was this capturing the very moment when boredom gave way to daydream?

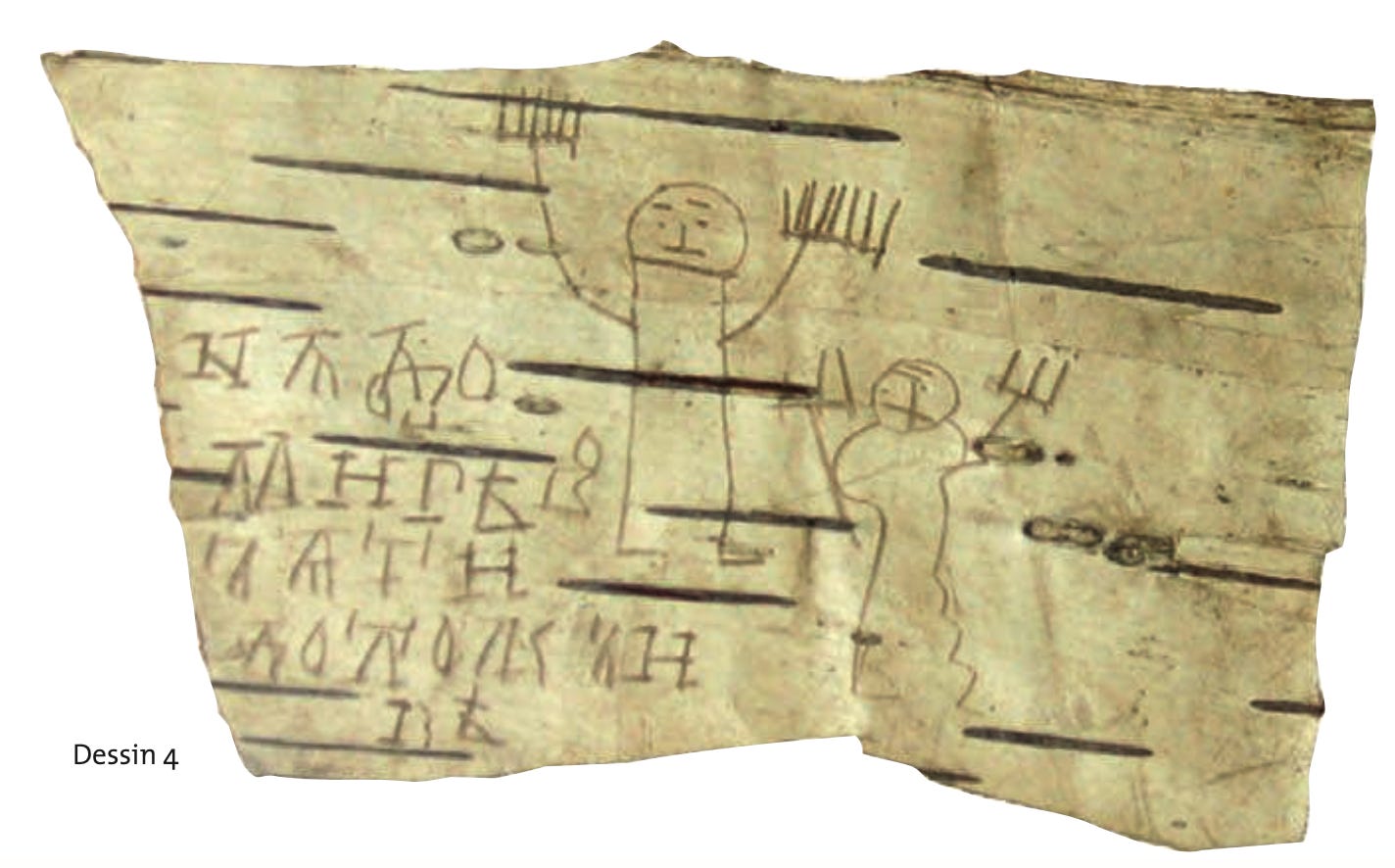

Another fragment shows Onfim next to a larger figure, with the caption: “This is my father.” Both father and son are drawn in a style that psychologists today might categorize as transitional between “tadpole” and conventional stick figures—each face cheerful, with disproportionately long limbs and spiky fingers fanning out like tiny rakes.

As the anthropologists René Baldy and Daniel Fabre argue in their thoughtful analysis of Onfim's drawings, Onfim’s work demonstrates that medieval children were capable of remarkable expressiveness. Onfim’s sketches suggest deliberate storytelling—a “graphic narrative” unfolding scene by scene, using shifts in scale, perspective, and emotional expression. One set of drawings is even a kind of proto-comic book, with a rider approaching from the right, then growing larger as he slays an opponent at center stage, and finally departing to the left.

In “Centuries of Childhood,” I wrote about how modern Westerners tend to systematically underrate the sheer variety of parenting practices throughout history. But of course, there is also a flip side to this: the universality of childhood. Anyone with children, or anyone who remembers being a child, will recognize Onfim and his world. It has barely changed at all.

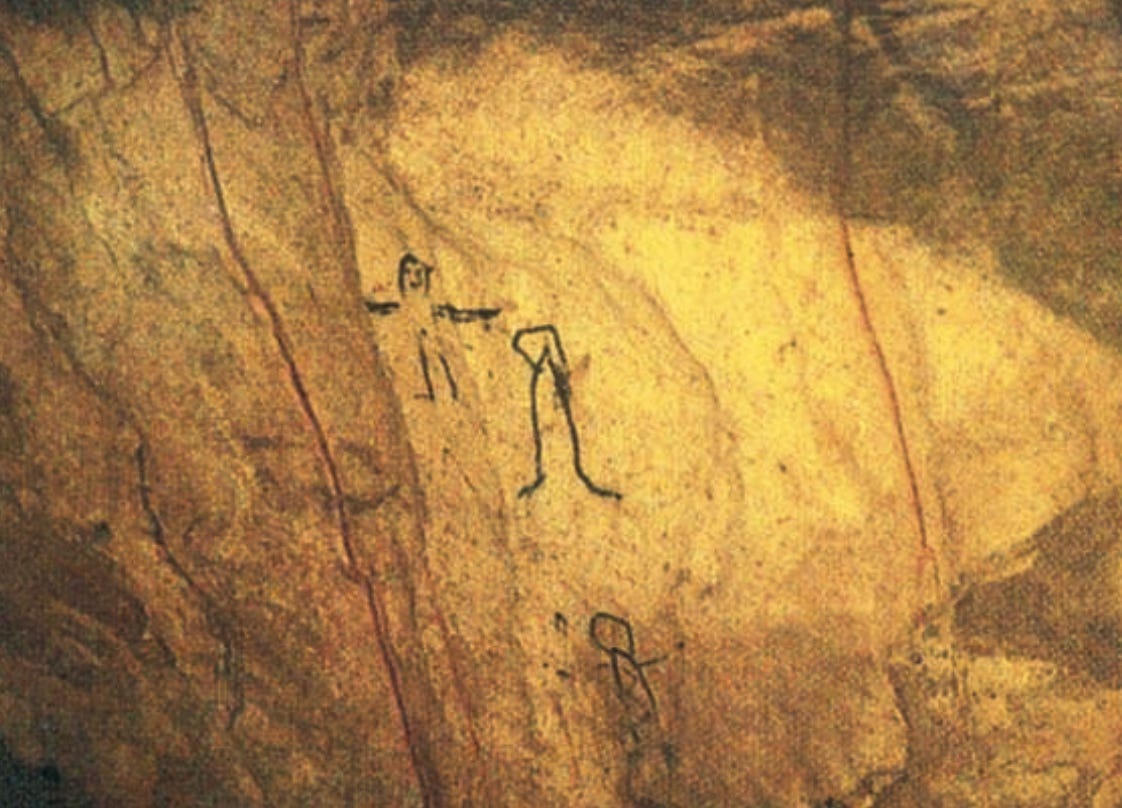

Because of Onfim’s reoccurring online virality (there’s an article about him virtually once a month), we tend to forget that he wasn’t some unique one-off. As Baldy and Febre relate in their article, another, rather darker set of child drawings from around 1150 CE was discovered in an abandoned iron mine near Sorèze, in southern France.

There, child miners had etched charcoal images on cavern walls. Unlike Onfim’s playful schoolwork, these figures have an unsettling poignancy: children drawing themselves in their work attire, some wielding picks, others with sorrowful eyes staring into darkness.

These images were less imaginative flourishes than signatures. Perhaps they were a way for children to assert their presence in an environment hostile to childhood itself.

Taken together, Onfim’s whimsical daydreams and the charcoal drawings of the Sorèze miners compel us to see the premodern world from a different perspective: one that was about three feet tall.

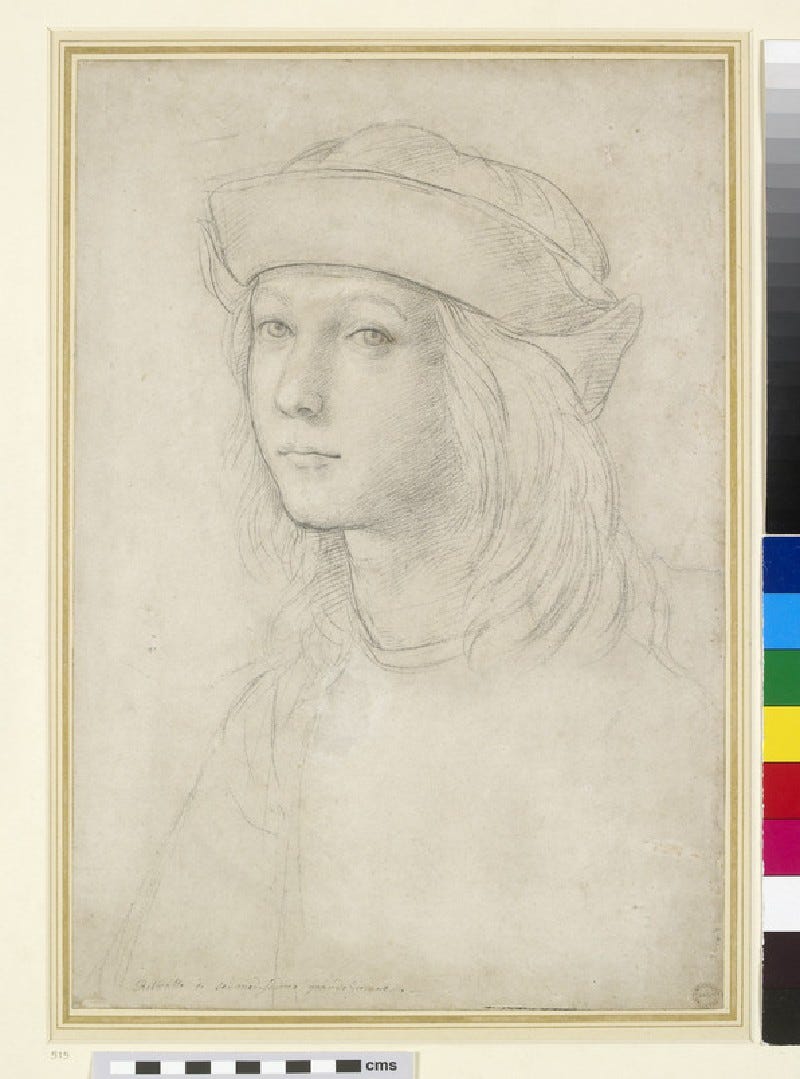

There are, of course, several more famous child-authored artworks from the medieval and early modern periods. Probably the most famous are these two self-portraits by two extremely talented fifteenth-century teenagers: Albrecht Dürer and Raphael.

But these belong to a very special category of child art: the juvenilia of the genius.

There’s also another, similar category: children’s doodles left behind on the papers of famous people. My favorite examples being these drawings of vegetable battles that Charles Darwin’s children left scrawled on some of the pages of his original manuscript for The Origin of Species:

For every unique survival like these, there are many millions that are lost. Children are continually making creative marks (as any parent with young kids knows all too well — cleaning them up has been a central preoccupation of my life over the past couple years). If we assume this is a human universal, and I think we can, then it is a bit staggering to imagine just how much child artwork has ever been created.

Here’s a back of the envelope calculation: there have been around 100 billion humans, and the average kid makes about 1-2 drawings (or other forms of artistic mark-making) each day for a period of, say, 10 years.

That adds up to over 500 trillion individual artworks by children. Surely that’s not accurate, at all. But it’s likely roughly the right order of magnitude.

As for Onfim, although archaeologists have been aware of him since the first Soviet digs in the 1950s, it was really only until the era of the Internet that his drawings became widely recognized.

I’m glad they are. They force us to see childhood not as something that takes place in an eternal present, but as something with as deep a history as anything else that is a central part of what it is to be human.

• It’s surprisingly hard to find a full archive of Onfim’s drawings online, but his Wikipedia page and the article by Baldy and Fabre (n French) is a good place to start. This archive in Russian seems to be a searchable digital repository of the Novgorod medieval birchbarks (beresty).

• “Yet Ferriss’ forward-looking vision also repeatedly evoked the ancient past. The pyramid skyscraper that he promoted was, in his own description, a ‘modern ziggurat,’ the monumental architectural form of ancient Mesopotamian cities.” (from a new essay with lots of great images of early monumental skyscraper designs in The Public Domain Review)

• In true 18th century style, is offering a $10,000 essay prize. Here’s the link.

• And here’s a 2017 Cabinet Magazine article on Onfim and the Novgorod birch mark texts from the proprietor of The Hinternet, Justin Smith-Ruiu.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·