By Chris Yarrell

April 17, 202511:00 AM

Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

On June 15, 1982, in a narrow 5–4 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a landmark decision in Plyler v. Doe, striking down a Texas law that sought to deny public education to undocumented children. In doing so, the court affirmed that access to basic education is a vital public good—essential not only to individual development, but to the functioning of a democratic society—and that states cannot arbitrarily withhold it from children based on immigration status. While Plyler did not formally alter the tiers of judicial scrutiny, it deepened the court’s engagement with this more searching form of rational basis review—particularly when evaluating laws that burdened disfavored or politically powerless groups.

Today, with a Supreme Court that has shown a readiness to overturn long-settled precedent and a growing number of state legislatures openly suggesting that Plyler should be revisited, the case—and the doctrinal architecture it helped shape—is under threat. At least four states—Texas, New Jersey, Tennessee, and Oklahoma—are actively advancing measures to restrict undocumented students’ access to free public education, with a fifth state—Indiana—poised to follow. These bills are part of a broader policy road map outlined in Project 2025—a blueprint spearheaded by the Heritage Foundation to reshape federal law during the second Trump term—which explicitly contemplates a legal challenge to Plyler as a mechanism for narrowing Equal Protection guarantees for immigrant students.

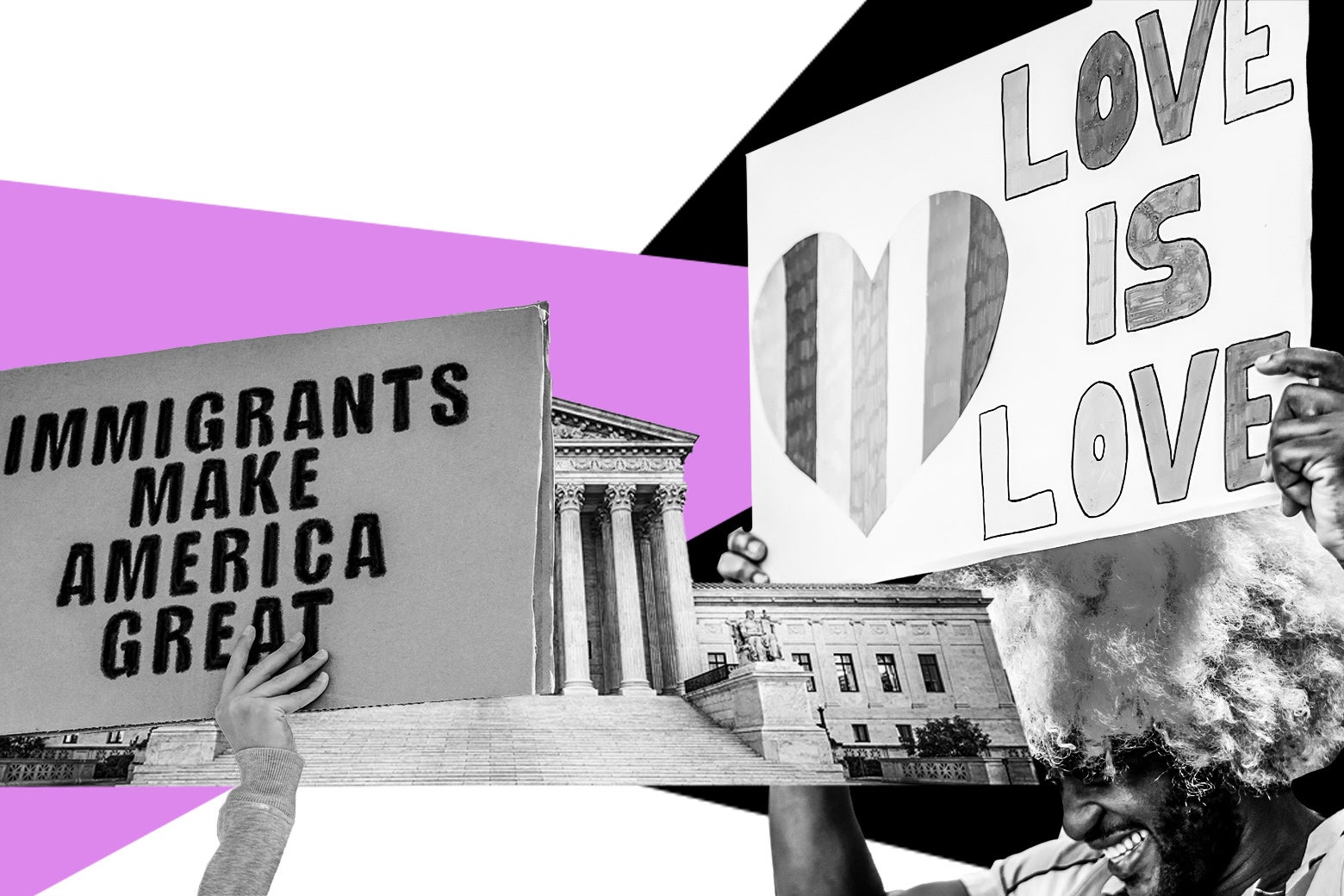

But this isn’t just a story about education or immigration. If Plyler falls, the consequences will reverberate across constitutional law, potentially unraveling the fragile protections that underpin modern LGBTQ+ rights, disability rights, and more. To understand why, we need to examine a subtle, but powerful, legal concept that Plyler helped reinforce: rational basis review “with bite.”

Under traditional rational basis review—the lowest, most permissive tier of judicial scrutiny—laws are upheld so long as they are “conceivably” related to a legitimate government interest. This form of judicial review is deeply deferential, often functioning as a judicial nod to legislative authority. But Plyler followed a different path.

Rather than simply accepting Texas’ justification for denying education to undocumented children, the Plyler court interrogated whether the Texas law’s purported aims—budgetary savings and discouraging unauthorized immigration—actually justified the harm imposed. It concluded they did not. This more probing approach mirrored the logic the court had used a decade earlier in U.S. Department of Agriculture v. Moreno, where it struck down a law that excluded households with unrelated individuals living together from food stamps. Indeed, in reviewing the legislative history, the court found that the law’s true purpose was “to prevent so-called ‘hippies’ and ‘hippie communes’ from participating in the food stamp program.” That aim, the court held, could not justify the law, as “a bare congressional desire to harm a politically unpopular group cannot constitute a legitimate government interest.”

What sets rational basis review with bite apart from its namesake, then, is its focus on substance over form. Courts applying this framework do not simply rubber-stamp the government’s stated rationale; they examine the actual purpose and impact of the law. If the true aim is punishment, stigma, or exclusion of a disfavored group, the law is constitutionally suspect—even if it avoids triggering intermediate or strict scrutiny.

This approach has become indispensable in expanding and protecting LGBTQ+ rights. In Romer v. Evans, the court used it to strike down a Colorado amendment that barred anti-discrimination protections for members of the LGBTQ+ community. In Lawrence v. Texas, it was key to invalidating laws criminalizing same-sex intimacy. And in Obergefell v. Hodges, the same logic helped support the recognition of marriage equality. These decisions didn’t just rest on abstract ideals—they reflected the court’s willingness to move beyond formal classifications and engage seriously with the actual purpose and impact of the laws at issue.

But despite its doctrinal importance, rational basis with bite has always rested on shaky ground. As I’ve written elsewhere, the Supreme Court has never clearly defined when and how it applies. Its deployment has been inconsistent, and its contours remain vague. This lack of clarity makes the framework dangerously susceptible to revision or outright rejection by a court more interested in deference to ideological fellow travelers than in equality.

If the decision is overturned, the result would be more than the exclusion of undocumented children from school—it would signal that laws targeting politically unpopular groups need not survive any meaningful judicial inquiry, unless a suspect classification or fundamental right is at stake. That shift would ripple across Equal Protection law, inviting states to pass legislation that once would have been struck down as constitutionally impermissible.

We’ve already seen the playbook. In the wake of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which overturned Roe v. Wade, conservative states wasted no time pushing aggressive anti-abortion laws. But the rollback didn’t stop there. Many of these same states are now advancing policies targeting trans youth, LGBTQ+ families, drag performers, and anyone who deviates from a narrow vision of identity and family. If Plyler is overturned, it could open the door to even broader legislative attacks, this time shielded by the most permissive form of judicial review that permits discriminatory laws to survive so long as any conceivable justification—no matter how speculative—can be asserted.

And the stakes could not be higher. Justice Clarence Thomas’ concurring opinion in Dobbs explicitly invited the court to reconsider Obergefell and Lawrence, hinting at a future in which the very legal foundations of LGBTQ+ dignity and autonomy are once again up for debate. Reversing Plyler could provide the doctrinal means to follow through on that invitation—by collapsing the analytical framework that has protected so many from majoritarian overreach.

Ultimately, Plyler embodies a constitutional insight as urgent today as it was in 1982: that equality is not achieved through formal neutrality alone. It requires courts to engage with the real-world consequences of laws—and to reject those that operate as tools of unjustified exclusion. If we abandon that insight now, we risk unraveling not just one case, but a generation of hard-won protections built on its logic.

The question before us isn’t whether the court is willing to revisit precedent. We already know the answer. The question is whether we will recognize Plyler for what it is: a keystone. And if we let it fall, we may find far more collapsing in its wake.

Sign up for Slate’s evening newsletter.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·