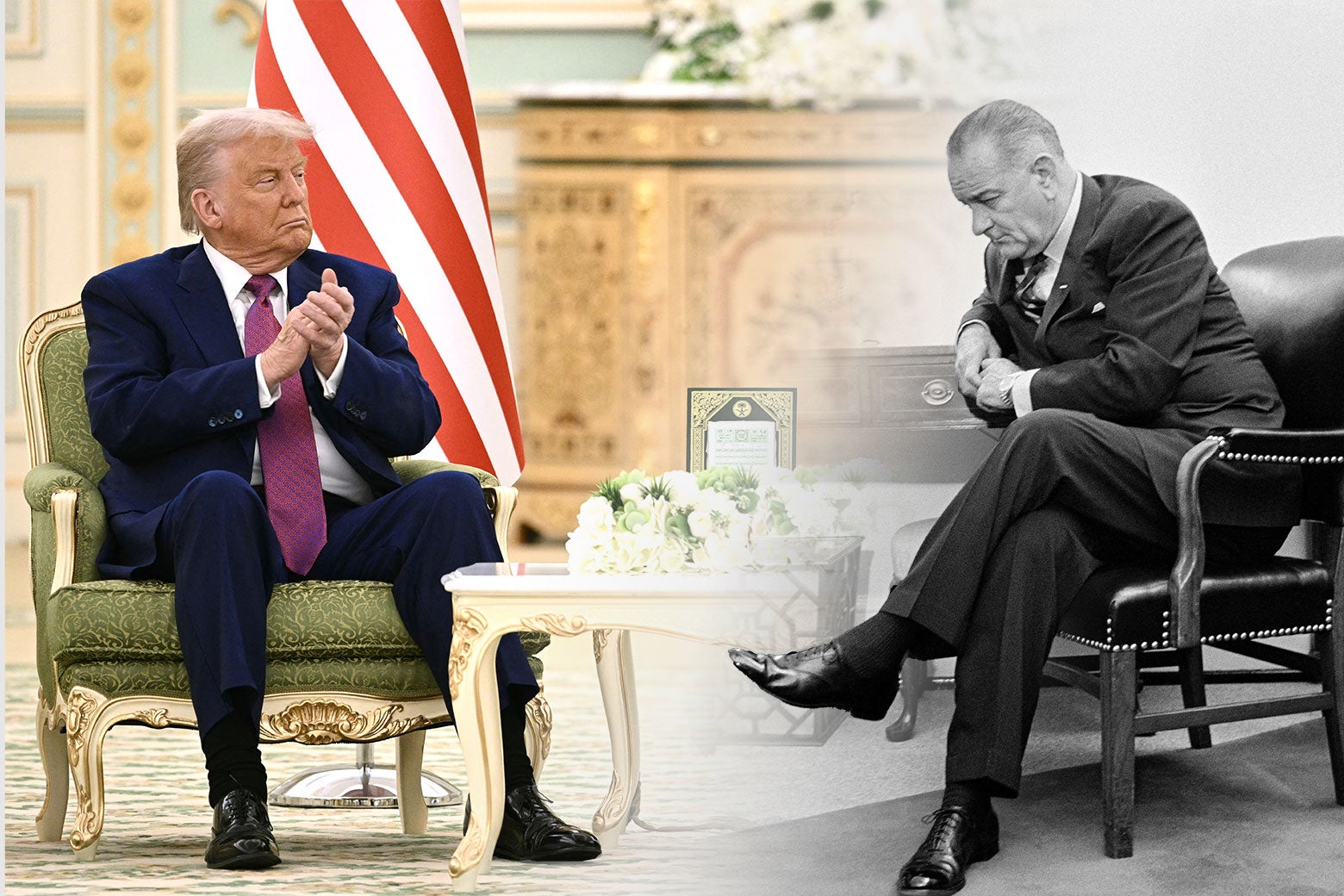

Lyndon Johnson made an America that strove for justice. But he made a major compromise that Donald Trump has been exploiting for years.

Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

At the end of his presidency, Lyndon Johnson returned to the massive Texas ranch that was an emblem of his sincere passion for the land of his childhood, a romantic vision of his connections to the place—and a fruit of his corrupt practices during his decades in government. Joined by several aides he’d tasked with helping him write his memoir, Johnson talked while a tape recorder kept track. The aides, who included the former White House Fellow Doris Kearns, eventually presented Johnson with a couple of chapters based on the recordings. Johnson exploded: “Goddammit!” he roared. “Get that vulgar language of mine out of there. What do you think this is, the tale of an uneducated cowboy? It’s a presidential memoir, damn it, and I’ve got to come out looking like a statesman, not some backwoods politician.”

Johnson got his way and then some, and he eventually published a memoir, Vantage Point, that was characteristically misleading and almost unreadably dull. Years later, the historian Michael Beschloss published excerpts from a surviving transcript of the recordings, calling them “an astonishing window on the real Johnson.” But while they are a much better read than Vantage Point, I wouldn’t say they get at the real Johnson. Johnson, I’ve come to believe, was far too complex a person for any facet of him to qualify, on its own, as real. In that way, he seems genuinely representative of the country he once led.

Still, there was a version of him, occasionally in evidence in the transcript, that does read as authentic in the ways we often talk about authenticity in American men: crass, cutting, folksy, sometimes hilarious, sometimes breathtakingly cruel. Away from the public, where he was more buttoned-up, Johnson spoke in terms that you could easily imagine coming from our current president—if only Donald Trump were more clever and not from New York. At one point in the transcript, Johnson explains, “The vice president is generally like a Texas steer—he’s lost his social standing in the society in which he resides. He’s like a stuck pig in a screwing match.” In justifying the country’s role in the war in Vietnam, he says, as he often did, “But if you let a bully come in and chase you out of your front yard, tomorrow he’ll be on your porch, and the next day he’ll rape your wife in your own bed.” And he was known to complain of the Kennedy loyalists whose education and social graces convinced him, not incorrectly, that they looked down at him, “All those Bostons and Harvards don’t know any more about Capitol Hill than an old maid does about fuckin’.”

In 2018 I started writing a book (a book-length poem, actually; I’m a weirdo) about Johnson. I promised myself that I wouldn’t write about Donald Trump. I was still hoping that Trump would be a relatively short-lived phenomenon, and I believed that Trump, like any good narcissist, was a terrible lens for looking at anything other than himself. He’s the world’s most fascinating uninteresting person: We can never stop talking about him, but there’s almost nothing useful to say. While the damage he’s doing requires even more attention than it gets, there’s mostly just the obvious to say about the man himself. Even his lies are authentic manifestations of his psyche, so obvious that they effectively analyze themselves.

Now the book is done. I still have no desire to use Trump to think about LBJ. But I’m starting to see the value in using LBJ to think about Trump. Because in almost every facet of his political career—his style, his agenda, his keen nose for everyone else’s hypocrisy, his disdain for the complex federal bureaucracy, for complexity in any form—Trump is reacting to the America that Johnson helped compose, one that is more just but less local, more intricate, and harder to understand. Trump’s electoral success comes in large part from his ability to make a substantial number of voters feel that he is placing them back at the center of their own lives, after years of feeling that their country has moved on from them. I always go back to the dynamic of his rallies. Trump loves to tee up a transgression, and when he lands it, the transgression thrills, because it both rejects the imagined constraints of someone in his position as their otherwise-unlikely stand-in and invites a renewed sense of belonging. The audience gets to create a place where everyone inside the perimeter is free and happy and good just as they are, because they have reclaimed their ownership of the American story.

Trump was 17 when Johnson became president. In his late 20s, he and his father had to sign a consent decree after repeatedly violating the Fair Housing Act, the last major law of Johnson’s presidency. And he has built his political career on a slogan of lost American greatness that plants the flag of national majesty in the decade just before the one that Johnson’s presidency helped to alter, inflame, and define.

For all the distance between them, Johnson and Trump are actually a lot alike. The presidency selects for certain excesses and deformities of character—plenty of which both men had and have in spades. There’s the larger-than-life personality embodied in a massive carnality; a pattern of using women’s bodies as a means of expressing their unchecked power and liberty; and an inexhaustible need to be loved and revered—as well as an inability to tell the difference between the two. And then there’s something rarer among presidents: an ability to substantially and lastingly change both America and the world it dominates.

The differences between the men are even more numerous, but two seem especially useful. First, whereas Trump’s peculiar political talent resides in simplification, reducing ideas to impulses, Johnson’s success depended on a mastery of legislative complexity, which tended to result in making the world more complex in turn. And second, whereas Trump instinctively works to narrow the circle of compassion, obligations, and fundamental human rights, Johnson, as president, committed much of his political fortune to a breathtakingly expansive attempt to enlarge it. In the intersection of the two, Johnson helped create the conditions in which Trump’s unpresidential rise and return to the presidency could take place.

Lyndon Johnson loved government. He loved it for its potential to improve people’s lives—and he loved it for the ways it answered to his genius for understanding elaborate systems and the individuals who make them work. He loved an ideal of America incompletely embodied in the work of his hero, FDR, and the legion of government agencies FDR created (including the National Youth Administration, whose Texas division Johnson ran for two years before launching his first congressional campaign).

A few nights after John F. Kennedy’s assassination, Johnson sat up late with a group of trusted advisers, debating his plans for an unplanned presidency. When the advisers argued that a focus on civil rights would be politically damaging, Johnson barked at them: “Well, what the hell’s the presidency for?”

Ultimately, Johnson would pass three major civil rights bills, including the Fair Housing Act—legislation that significantly altered the orientation of American law even as, as even Johnson would admit, it failed to get the country close to true equality. He would also sign legislation that eliminated racist immigration quotas; created Head Start, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Medicare, and Medicaid; and increased the minimum wage while expanding it to include more than 3 million additional workers whom Roosevelt had left out, partly to appease the segregated South. He authorized legislation providing federal funding for schools. He signed farm aid, assistance for Appalachia, funds for mass transit in cities, increases in Social Security and civil service pay, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, legal services for the poor … the list goes on and on.

He was able to do all that in part because the combination of Kennedy’s assassination, Cold War competition for moral supremacy, and nonviolent protests in the South created a temporary but large and passionate majority—and, by extension, a simpler political terrain for Johnson to traverse. Early polls showed that only 3 percent of respondents disapproved of LBJ, even though by then he had already announced that civil rights would be the central focus of his administration.

But even with that advantage, it’s hard to imagine any other politician who could have accomplished what he did. Johnson was uniquely capable of tracing and tacking through the hundreds of veto points that compose power in Washington, particularly in the Senate, which then more than now was an intricate weave of interests and prerogatives. He did it through force, persuasion, and an understanding so detailed that it would be incomprehensible to the rest of us without the aid of Robert Caro—a biographer who is himself uniquely well suited to Johnson (and whose books on Johnson are great literature yet exceptionally good reads). In some cases, Johnson overran obstacles, but at least as often he incorporated them, creating more law and more complexity, as well as provisions that sometimes wrote dire consequences into programs meant to make America more just. (The Fair Housing Act that was used to sue the Trumps includes an anti-riot clause, always ripe for abuse, that establishes just the kind of power Donald Trump loves to exploit.) It doesn’t seem to have worried him all that much. The point, he believed, was to pass the bill. You could always go back and improve it later on.

Johnson left behind a government that was harder to understand and—thanks in part to his moral and political failures in Vietnam, as well as his increasingly glaring dishonesty—harder to trust. The further nationalization of politics was inevitable if he was going to make any progress. Jim Crow states were never going to uproot Jim Crow. And the amount of human misery he helped dissipate easily justifies the attendant growth in the federal government. But it’s also true that in trying to include something for everyone in his Great Society, Johnson created something—many things—for everyone to object to. And so the new world Johnson ushered in was also one that felt further removed from many people’s lives. Much has happened since then to increase that alienation—the globalization of manufacturing, our increasing confusion of capitalism and ethics, the Democrats’ long drift from labor to Wall Street, the loss of any civic trust that could allow a politician to command, “Ask not what your country can do for you …,” the evolution of a liberal shibboleth based on laughing at the kinds of people who would eventually form Trump’s base, massive tidal swells of racism and xenophobia—but much of that has worked itself out inside the complex and nationalized systems LBJ created and grew.

Scaling compassion to the level of justice is an achievement, and it tends to atrophy fast. Johnson wrote his achievements into law, where they could outlast the brief historical window he passed them through. But I suspect that the entanglement of complexity and justice that this required has something to do with the window that Donald Trump has come crashing through.

Any transformative presidency requires a coincidence of individual and occasion, and the occasion for Donald Trump’s ouroboric anti-elitism is one in which most Americans feel alienated from the systems that govern their lives and what they believe to be those systems’ concerns. When Trump stands in front of a crowd and speaks with the kind of crassness Johnson felt the need to hide from public view, he’s communicating his disdain for the proprieties those systems insist on—and his countervailing authenticity. Trump is a strangely local figure. Whereas Johnson worked to remove “the taint of magnolia” on his way to becoming a national leader, Trump seems to be descending further and further into a caricature of himself, a franchised version of a Mafia don who left New York only to travel back and forth between his branded resorts, someone who could win the presidency twice but still maintain the illusion that he is not, will never be, a politician. Even his determination to eat the same few meals over and over again, while not actually the character flaw it’s made out to be, is revealingly parochial—an extreme version of the American tourist who, feeling lonely far from home, gives in and heads to McDonald’s for a meal. He is simple, and his simplicity reflects, among other things, a desire to live at a scale where we can matter, even as we reach for powers and status we feel we’ve been denied.

It’s hard to imagine what America will look like even a few months from now. But one of Trump’s biggest political weaknesses may be that he works against a key element of his appeal—the promise of a simpler world in which distant, seemingly unaccountable systems no longer require so much of people’s time, care, and attention—by making it so hard to look away. Trump is most successful when he seems to stand for his voters, but he can’t help making everything, always and everywhere, exhaustingly, about himself, and thanks to this habit, everything ends up more unpredictable and harder to understand.

Part of the genius of the nonviolent Civil Rights Movement, which Johnson sometimes disdained but unquestionably drew power from, was that it made justice seem simple. It was hard to look at the savagery of, for example, Selma—as most Americans did, in photographs and on television—and not see what was wrong. A successful Democrat, one who can unify the party’s current coalition while also energizing a much larger number of Americans, will need to offer more than justice—but I think part of the answer may be in once again making kindness seem simple, even at the scale of justice. We need an ideal of American justice that a majority of Americans will find it easy to believe in. I don’t claim to know how to construct that. But I’m pretty sure it will have to be straightforward and earnest enough for a majority of Americans to feel it almost as immediately as they feel their own desire to belong.

Sign up for Slate's evening newsletter.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·