Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

Ever since President Donald Trump took office, he’s been violating the law left and right to reach his mass deportation goals—and he’s faced an onslaught of lawsuits, a majority of which he’s losing.

In private, Trump has said he wants to deport 1 million immigrants in 2025, according to the Washington Post—but in his first 100 days, the numbers suggested he was not deporting people on a greater scale than past presidents. The judiciary—including judges appointed by Trump himself during his first term—has been the main line of defense against his lawless actions.

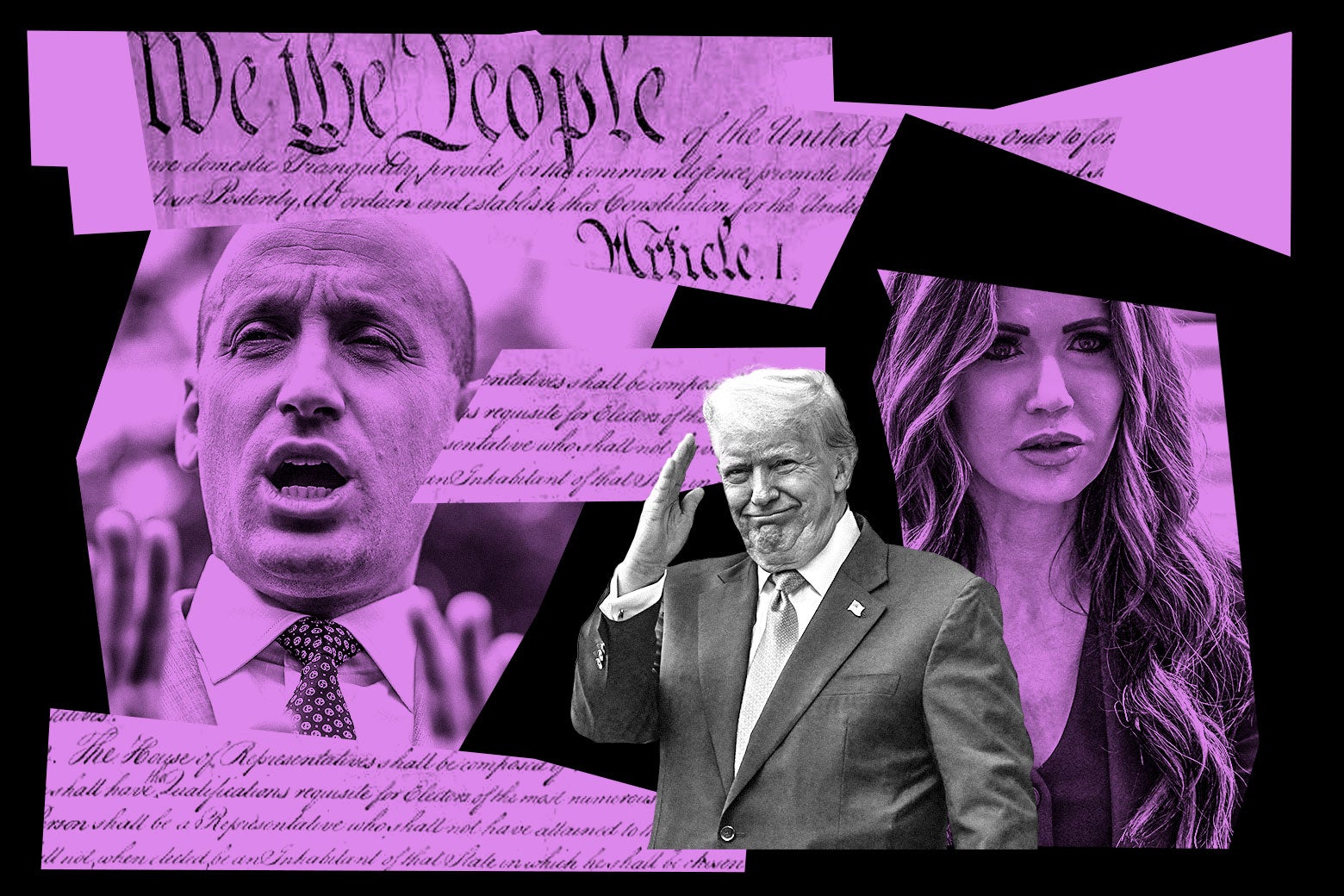

The courts have particularly been a thorn in the Trump administration’s side when it comes to the case of Maryland man Kilmar Abrego Garcia, who the administration admitted was deported by mistake. Multiple federal judges ruled Abrego Garcia must be brought back home, and even the Supreme Court ordered the Trump administration to “facilitate” his return, yet the father of three remains in El Salvador’s CECOT megaprison. The Supreme Court went even further earlier this month, blocking Trump’s efforts to continue the illegal extradition flights and declaring that the affected migrants had not been granted their full due process rights during the administration’s attempts to rush deportation flights to third-party countries. Instead of respecting court orders, the Trump administration is now eyeing a workaround: Cutting out the courts by suspending habeas corpus.

The administration has its eye on habeas corpus because it’s a legal principle that requires the government to come before a judge and provide a reason for detaining and imprisoning people. In recent weeks, Trump officials have begun suggesting that they can simply revoke habeas corpus. Deputy chief of staff Stephen Miller told reporters that “the writ of habeas corpus can be suspended in a time of invasion. So I would say that’s an option we’re actively looking at.” During a recent congressional hearing, Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem incorrectly defined habeas corpus as “a constitutional right that the president has to be able to remove people from this country and suspend their rights.”

The executive branch, though, does not have the unilateral authority to simply pause habeas corpus as it pleases. In order to understand what habeas corpus is and how it can be suspended—if it can at all, I spoke with Steve Vladeck, professor of law at Georgetown University and author of the Substack newsletter One First.

Habeas Corpus Is a Constitutional Right

Habeas corpus gives anyone who believes they have been unlawfully detained by the government a way to contest the legality of their detention. It was adopted in British common law and was formally codified under the Habeas Corpus Act of 1679, where it remains in effect in England today. When the founders established the legal foundation of the United States, they brought this concept along with them.

Today, habeas corpus is enshrined under Article 1 of the Constitution. It comes before the Bill of Rights, which, Vladeck believes, suggests that the founders wanted to prioritize establishing the existence of habeas while also specifying the only circumstance under which it could be taken away.

“What habeas really is, it’s a guarantee of judicial review. That is, in some respects, more than just a right,” Vladeck told me. “That is actually a fundamental constraint on the government, where even if you had no other rights, you would be entitled to have a court say so, as opposed to the executive branch.”

It Can Only Be Suspended in Rare Cases

The Trump administration wants to cut off immigration detainees’ pathway for judicial review, essentially clearing the way for deportations without interference from the courts. Suspending habeas corpus is technically possible under the suspension clause, which states that “the Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.” This clause has only been invoked four times in U.S. history: in 1861 during the Civil War; in 1871 when the Ku Klux Klan was committing mass violence against Black Americans in the South; in 1905 during a rebellion against the American military in the Philippines while it was still a U.S. territory; and in 1941, in the midst of the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

The suspension clause can only be invoked by Congress, not the president, despite what the Trump administration has said. It also specifically limits the circumstances under which habeas can be suspended, rather than revoking habeas corpus in its entirety, because the founders wanted to ensure that judicial review of detention cases could still continue even in a true emergency. The reality is that the Trump administration is likely hoping that “no one actually pays close attention to the text,” Vladeck said, “because it’s not just that we’re not actually being invaded by anyone right now, it’s that even the suspension clause does not authorize suspensions by the president, ever.”

It’s worth noting that even during the War of 1812 when Great Britain invaded the U.S., the suspension clause was not invoked—it’s meant only for truly egregious national emergencies. Right now, of course, Trump is trying every potential legal tool in the kit, as further demonstrated by his use of the Alien Enemies Act, a separate wartime law passed in 1798 that’s only ever been invoked three times in U.S. history.

“I think what the Trump administration is counting on is that it can sort of discuss suspending habeas corpus at a high enough level of abstraction that it all appears to blur together,” Vladeck explained, “when the legal authorities are in fact much, much more nuanced and much, much more specific.”

Habeas Corpus Is a Critical Executive Branch Check

Miller said that whether the Trump administration tries to suspend habeas corpus or not depends on “whether the courts do the right thing or not.” He was basically saying the quiet part out loud: that it’s a threat from the executive branch to twist the arm of the judiciary.

Since Trump began his second term, habeas corpus has been critical in keeping his administration in check. It is the first and only legal pathway for challenging immigration detention. It’s how Rumeysa Ozturk, a Turkish international student at Tufts University, was able to get out of immigration detention in Louisiana, along with Mohsen Mahdawi, a Columbia University student who is a lawful green-card holder. Cristian Farias, a courts reporter for Vanity Fair, told Slate’s Dahlia Lithwick that “to file a habeas petition is basically what ensures that you won’t be sent to a black site or put in a prison without ever getting out.”

Considering also that there have been at least three cases where a federal judge ordered the Trump administration to bring back wrongfully deported immigrants, habeas is the sole lifeline for detainees to get back their freedom. “Without habeas, there’d be no mechanism by which someone could challenge the Trump administration’s designation that they are, for example, an alien enemy,” Vladeck said. “There’s nothing to stop the government from pointing to any of us, citizen or noncitizen, and saying, you know, ‘You are an alien enemy’—or an undocumented immigrant.”

Sign up for Slate's evening newsletter.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·