A dark mystery shocked America in the early 1990s, from prime-time shows to Congress. It’s largely been forgotten. It shouldn’t be.

Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

On Sept. 26, 1991, Capitol Hill was on edge. There was a big congressional hearing that morning, and nobody was sure if the star witness was going to make it.

It was around 9 a.m. when her wheelchair rolled into the Washington hearing room. She was immediately swarmed by photographers. Millions of Americans already knew her story. Now it was obvious that she didn’t have much time left. She was 23 years old and weighed just 70 pounds.

Someone knelt down and clipped a microphone to her lapel, a few inches from the crucifix that dangled from her neck. The room fell silent, except for the clicking camera shutters.

The woman could barely speak. But she mustered the strength to make one last public statement.

“I like to say that AIDS is a terrible disease that you must take seriously,” Kimberly Bergalis said, her voice quavering. “I did nothing wrong, yet I’m being made to suffer like this. My life has been taken away. Please enact legislation so that no other patient or health care provider will have to go through the hell that I have. Thank you.”

AIDS had already killed more than 100,000 Americans. A few months before that hearing, in June 1991, the New York Times had marked a decade of the epidemic by recalling the brief 1981 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that described an outbreak of pneumocystis carinii pneumonia among five gay men in Los Angeles. The paper remembered an early optimism among researchers that the outbreak would be contained, limited to what the Times called “wildly promiscuous” gay men.

That faded quickly. The unimaginable spread of the disease and its death toll had since stunned the country and world. “10 Years of AIDS Battle: Hopes for Success Dim,” the Times’ headline read.

Though most of the dead were gay and bisexual men, by 1991 the face of the epidemic had become someone else entirely. Kimberly Bergalis was young, attractive, and, crucially, straight. Today few remember her name. But in the early ’90s, she was everywhere, a fixture in magazines and on the TV news, an unlikely victim devastated by a cruel disease.

The press and the public found her fascinating not just because of who she was and how she looked. They were also captivated, and terrified, by how she’d supposedly gotten HIV. Her account of it was scandalous and strange—almost unbelievable.

In December 1987, when Bergalis was 19 years old, she went to a dentist in Jensen Beach, Florida, to get her bottom molars pulled. “She said that she remembered he wore gloves and a mask and she was awake the whole time,” a CDC investigator recently recalled to me. The whole thing seemed uneventful—but Bergalis told the investigator that she’d also heard a rumor that the dentist might have AIDS. Everything would snowball from there, grabbing America’s attention and creating a monumental controversy.

It is hard to overstate the AIDS paranoia of the early 1990s, the intense fear and powerful stigma of the disease. Drug treatments were experimental, and little was known about how long they might keep people alive. And the people driving the spread were seen by many Americans as degenerates who couldn’t control themselves.

All these decades later, despite medical and social progress, the epidemic is far from over, even in the United States, and stigma against HIV-positive people persists. The new Trump administration’s cuts and policies seem certain to make things worse, if not send us back in time.

Back in 1991, AIDS deaths were still soaring, with the peak of the American epidemic still four years away. And the story of Kimberly Bergalis was an irresistible flash point.

That’s largely because of who she believed had infected her. The man whom she accused would be turned into a national villain, without America ever knowing who he really was. Even now, Bergalis’ own story remains incredibly thorny. It’s a warning to a country that still hasn’t fully reckoned with the national disgrace of the AIDS epidemic. It’s also a parable about how we decide who’s guilty and who’s innocent—and about whose lives we ought to protect.

This story was adapted from an episode of the One Year podcast. Evan Chung and Kelly Jones were the lead producers. There was additional production from Olivia Briley. Listen to the full version:

When Kimberly Bergalis left for the University of Florida in 1985, it felt as if her life were finally starting. Two hundred miles away from her strict Catholic parents, she soaked her hair in lemon juice to make it lighter and decorated her dorm room with a Pat Benatar poster. She made good grades in her business classes and dreamed of becoming an actuary.

In the spring of 1989, a few months before she was scheduled to graduate, she got a job waiting tables. On her first day at work, she fainted. She got a sore throat. Antibiotics didn’t make it any better.

By Christmas, she had gotten too weak to manage on her own. She moved back home to Florida’s Atlantic coast. Her parents often had to carry her around the house. Doctors checked her out for everything: diabetes, hepatitis, leukemia. Her mother, a public health nurse, suspected it might be something else.

Bergalis’ first HIV test wasn’t conclusive. The second came back positive.

She was in shock. She was 21 years old, at a time when an HIV diagnosis was basically a death sentence. And she had no idea how she’d gotten infected.

In the early 1990s, state health departments asked the CDC for help when they couldn’t figure out how someone had gotten HIV. “She was very interested in talking to us to try to figure things out,” said Carol Ciesielski, a doctor who worked in the CDC’s AIDS surveillance branch at the time.

HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, gets passed from person to person through blood and other bodily fluids, including semen. A few of the most common risk factors didn’t apply to Bergalis: She wasn’t an intravenous drug user. She’d never gotten a blood transfusion. As for sexual transmission—that was more of an open question.

Bergalis said that she’d had some sexual contact but never intercourse. Ciesielski pressed her to describe exactly what she’d done. Bergalis said later that the questioning was pretty rough—that she had gotten asked, “When you were on a date with so-and-so, can you tell us what really happened on that date and, you know, where was his hand and where was your mouth?”

Ciesielski acknowledged the awkwardness of these conversations. “I just felt sorry for her because, you know, it was so uncomfortable—you know, ‘I’m from the government, here to talk about your sex life,’ ” she told me. “But, I mean, they were very necessary questions.”

Ciesielski could tell that Bergalis was embarrassed, but she answered the questions and gave the names of two boyfriends. When the CDC tracked them down, both tested negative for HIV.

That meant that sexual transmission was looking unlikely. But Ciesielski had one more avenue left to explore: Bergalis’ medical history. That’s when she brought up the dentist she’d seen a few years earlier to get her molars pulled. Bergalis had heard whispers that he might have AIDS.

Even if that rumor about the dentist were true, it seemed like the longest of long shots that he’d given Bergalis HIV. As of 1990, there had never been a documented case in which an infected health care worker had transmitted the virus to a patient.

Ciesielski was skeptical that this would be the first such case, but she couldn’t rule out the theory until she’d done more investigating. That meant dropping in on the dentist. His name was David Acer. He was 40 years old, and he lived in a brick-and-stucco home with a fenced-in backyard and a fishing boat in the garage.

The moment Ciesielski saw him, she could tell that he was sick. He was extremely thin and pale. Acer confirmed that the rumor was true: He did have AIDS.

He told Ciesielski that he’d gotten tested outside town, to avoid the stigma that came with being HIV positive. He said that he was bisexual and believed he’d been infected by a sexual partner.

Acer had removed Bergalis’ molars three months after his initial diagnosis. While he

had no legal obligation to reveal his HIV status to his patients, he said he always took precautions, including wearing gloves at a time when the CDC didn’t officially recommend them for dentists.

He had shut down his practice in the summer of 1989, after he became too sick to work. When patients asked about Acer, they were told he had cancer.

Now, in 1990, Ciesielski explained that she was investigating a case of AIDS in one of his former patients. For confidentiality reasons, she couldn’t say which patient she was talking about. But she told me that Acer was very compassionate and concerned about that person’s well-being. At the same time, he didn’t think it was possible that he could’ve transmitted HIV to anyone who’d sat in his dental chair. Ciesielski told him there was only one way to know for sure: to collect a sample of his blood and test it.

Acer didn’t hesitate. He told Ciesielski to go ahead. “We sat at his kitchen table and I drew his blood, and then we went back to the health department, packed it up, and sent it off to Atlanta,” she remembered.

The CDC had collected Bergalis’ blood too and sent off both samples for genetic testing. Today this sounds like the obvious next step. But at the time, it was a totally new concept—no one had ever done DNA analysis to figure out if one person had transmitted HIV to another.

Scientists in Georgia, New Mexico, and Scotland took up the challenge. And when their tests were done, they all reached the same conclusion: These two strains of HIV were a very close match.

Ciesielski and the rest of the CDC were feeling a lot less skeptical. They now believed that it was actually likely that Bergalis had been infected by her dentist. That meant they were looking at the first documented case of a health care worker transmitting HIV to a patient. And the implications were enormous.

If there were even a slim chance of getting HIV during an ordinary dental procedure, that message would scare a lot of people. The fear of AIDS was already off the charts. So before the scientists said anything publicly, they thought hard about how confident they really were. “It was a big decision,” Ciesielski said, “because if it turns out it wasn’t true, we would be accused of fueling all the hysteria that resulted.”

After weeks of debate, the CDC made its final decision in July 1990: The agency published an article explaining what it knew about the dentist and his patient but added a note of caution. It said that “the possibility of another source of infection cannot be entirely excluded.”

Not long after that article went out to the world, Bergalis was with her parents, watching the evening news. On NBC, Jane Pauley announced the lead story—that “for the first time, a patient was infected with the AIDS virus by her dentist.”

There was no note of caution here: The national TV news was saying definitively that a patient was infected by her dentist. And while the CDC hadn’t identified Bergalis by name, it took her just a few seconds to figure out that she was that patient. “So it came out without her being told,” Ciesielski said. “It was horrible. It seems coldhearted.”

The scientists at the CDC had struggled over whether to give Bergalis a heads-up. Ultimately, they decided that they couldn’t, because they had an obligation to protect Acer’s confidentiality. But Bergalis and her family felt outraged that they’d been kept in the dark.

After the CDC released its report, health officials pleaded with Acer to go public so the people he’d treated would know they might be at risk.

On Aug. 31, 1990, the same day he was transferred to hospice care, the dentist signed his name to a letter. It began: “To my former patients: I am David J. Acer, and I have AIDS.”

In the letter, Acer suggested that his patients “contact the local health department for free testing and counseling.” He also defended his character. The letter concluded:

I am a gentle man and I would have never intentionally exposed anyone to this disease. I have cared for people all my life, and to infect anyone with this disease would be contrary to everything I have stood for. I am sorry if the news story has caused you fear and worry.

Those words would be his obituary. David Acer died of AIDS on Sept. 3, 1990, just three days after he’d signed that letter.

While the public now knew the dentist’s name, the patient’s identity was still a mystery. But it wouldn’t be for long. On Sept. 7, 1990, Kimberly Bergalis stood up at a news conference and said that she was the one the CDC had been talking about: the patient who’d gotten AIDS from her dentist.

Bergalis said that she’d been totally healthy before she got her molars removed. Now she was gravely ill, overcome with a nearly constant fever and debilitating fatigue. But she told the media that she was on a mission. “If this can be prevented from happening to another family, then I think that’s what needs to be done,” she said.

In that room packed full of reporters, Bergalis sounded calm and composed. Her parents were far less measured. “If there’s a hell on Earth, we’re here now,” said her mother, Anna. Her father, George, said that Kimberly’s “only shortcoming was her faith in the health care agencies. They failed, and she paid the price.” The Bergalis family wasn’t just using their words to go after the people they thought were responsible. They also filed suit against Acer’s estate and his insurance company.

Before that press conference in September 1990, no one had any idea who Kimberly Bergalis was. Afterward, it seemed as if everyone in the country knew her name. She appeared on CBS This Morning and the Today show, and she was on the cover of People. A few months later, she told Oprah Winfrey about the emotional toll of her diagnosis. “I’m angry,” Bergalis said. “I think I shouldn’t be here. I should be out dating and with my friends.” She added: “This shouldn’t have happened.”

That story in People said, “All who know her agree that Kimberly is the last person they would have thought might get AIDS.” Her father put it more bluntly. He said that his daughter’s “sickness would have been easier to accept if she’d been a slut or a drug user.”

In interviews, Bergalis maintained that she’d never had sexual intercourse. She explained in a television documentary that despite her Catholic upbringing, her decisions around sex “weren’t a religious thing”—that she’d just “never really met” the “right person.”

A lot of people weren’t buying it.

“I don’t think anyone believed at the time that she was a virgin,” said Michael Cheek. In 1990 Cheek was a young reporter at the Stuart News, a newspaper based out of Florida’s Treasure Coast. He was assigned to Bergalis’ story from the very first press conference. “My job was to get her to share with me the details of her life in a way so that I could poke holes in it,” he told me recently.

Cheek managed to persuade Bergalis to let him drive her to Miami, where she was having treatment. They did formal interviews at the beginning and end of that car ride, but for most of the trip they just chatted and got to know each other. “We talked about her life in college. We talked about what happened when she got sick. And I told her very early on I was gay,” Cheek said. He told me that Bergalis acknowledged that “her father was very homophobic. And she would actually say, ‘I’m not like my dad.’ ”

That day, Cheek asked Bergalis about her sex life. And by the time the car ride was over, his skepticism had melted away. “I found her absolutely genuine,” he said. “I don’t think she got it from any other person than the dentist.”

Although that was Cheek’s journalistic hunch, the American Medical Association and the American Dental Association were still skeptical. Regardless of Bergalis’ sexual history, they thought the scientific evidence that she’d gotten HIV from her dentist was paltry and unproven.

But it wouldn’t be long before that theory started looking stronger. Because Bergalis wasn’t the only one of David Acer’s patients to get infected with HIV.

In 1988 Lisa Shoemaker was in her early 30s and living in Jensen Beach, Florida. “I was unfortunately a part of a carnival,” she told me, laughing. It wasn’t just the carnival that was making Shoemaker miserable—she also hated the Florida weather and the bugs. And then, in the summer of ’88, everything got worse.

Shoemaker developed two abscessed teeth, one on each side. She went to see Acer. She said, “It looked like a good dental office, and it looked clean. People were friendly.”

She got to know that office very well, going about 10 times. A few months after she started that regimen, Shoemaker discovered that her boyfriend was cheating on her, with both men and women. So she decided to get tested. “They told me over the phone,” Shoemaker said: “You are HIV positive.”

She was devastated and confused. Because her boyfriend, strangely, was HIV negative. All she could think to do was move back to Michigan, where her parents lived, and try to get the care she needed.

Two years later, in 1990, Shoemaker’s father told her about a news story he’d seen about a dentist who’d died of AIDS—and who’d possibly infected one of his patients. Shoemaker and her father contacted the CDC. “I wanted to know exactly how it happened,” she said.

The CDC saw Shoemaker’s situation as very different from Bergalis’. While Bergalis didn’t have any obvious risk factors, Shoemaker did: her ex-boyfriend. And when the CDC asked him to get retested, this time he was HIV positive.

That seemed like the answer Shoemaker had been looking for. But when the agency sent off a sample of her blood for genetic testing, it got a surprising result: The strain of the virus in her blood was a close match to David Acer’s.

Ultimately, the CDC would find six former patients who tested positive for HIV and whose strain closely matched Acer’s. It was looking even more likely that the dentist had infected a whole group of people who’d passed through his office.

But the CDC still couldn’t explain how.

One theory was that a specific piece of equipment—a drill that Acer used on all the patients—wasn’t properly sterilized. It was also possible that he accidentally jabbed himself, through his gloves, on a needle or a patient’s teeth. Maybe that could’ve even happened six different times, because he was tired or stressed or suffering from a tremor or numbness in his fingers. And then there was a more sinister possibility: that Acer had intentionally infected his patients.

Although there wasn’t any good evidence to support that claim, the theory did get floated a lot. On ABC’s 20/20, Barbara Walters made Acer sound like a menacing gay villain, narrating darkly that while he “had what appeared to be a quiet and rather nondescript lifestyle, … what few people knew is that he drove to the gay bars in West Palm Beach, in Fort Lauderdale, where he could enjoy a completely different life he kept secret.”

David Barr was the assistant director of policy at Gay Men’s Health Crisis when the Kimberly Bergalis story created a media frenzy. He hated everything about it.

“He was gay, he knew he was positive, he was a villain, and Kimberly Bergalis, she was an innocent victim. And that was the story,” Barr said. “It made me angry that there would be so much media attention on How did this person get HIV?, and much less attention paid to How are we responding to this very large public-health crisis? That’s a bigger story to me than one infection in Florida.”

Barr had found out he was HIV positive in 1989. And he saw firsthand the toll that HIV and AIDS were taking on gay men. “The death was constant, and there was no time to really stop and take it all in—it was warlike,” he said. “But I think what made me most angry was just, there was virtually no response from the government. So it was really left to the community to sort of handle everything.”

Instead of being seen as victims in need of support, men like Acer were shunned as vectors of the disease and blamed for bringing AIDS on themselves through their behavior. In the letter he wrote to his patients before he died, the dentist had called himself a “gentle man.” Those words of self-defense were the only defense he’d get.

“No one wanted to be associated with David Acer,” Cheek, the reporter for the Stuart News in Florida, told me. “He was vilified in that community after Kimberly came forward.”

Cheek was one of the few out gay men in Stuart, a small, conservative city. But after spending time with Bergalis, he saw the story through her eyes, not Acer’s. “And I’m sure it creeped into my writing,” Cheek said. “He was just this villain that had done something to this beautiful human being I’d met. And I even stopped calling him Dr. Acer or David Acer. I just called him Acer.”

The more stories Cheek wrote, the simpler it all seemed to him. But then something happened that shifted his perspective.

It all started at a shopping mall, when he bumped into someone he knew at the food court. “And he looks at me and he says, ‘I don’t like what you’re writing about David right now.’ I kind of had this confused look on my face, I’m sure. And I said, ‘David? Who’s David?’ And he said, ‘David Acer.’ ”

This was someone who’d known David Acer personally. They were both part of a community of older closeted gay men in Stuart, Florida—a group that Cheek hadn’t known existed. There were no gay bars anywhere near Stuart, so these men met on Thursday nights at a local furniture store. They’d go in after closing hours to hang out and talk. It was the one place in town where Acer and his friends felt safe being themselves.

Cheek got an invitation to join them, and the group who met at that furniture store—six or seven men—all wanted to tell him about their friend David. How kind he was. How he sometimes wouldn’t charge them for dental work because he knew they couldn’t afford it. How, when one of their houses flooded, David was the first to show up at his door with a shop vac to help clean up.

Now Cheek was seeing the story differently, through the dentist’s eyes. He wanted to write about this David Acer—the pillar of his community, a man who was loved and mourned. But none of Acer’s friends were willing to be quoted and risk outing themselves.

“I asked every one of them,” Cheek told me. “I went back to them multiple times. And it was always no. They were too fearful.”

When I asked him if he thought it would’ve made a difference if he’d been able to publish that story, Cheek told me no—that “the world wanted to vilify gay men with AIDS.”

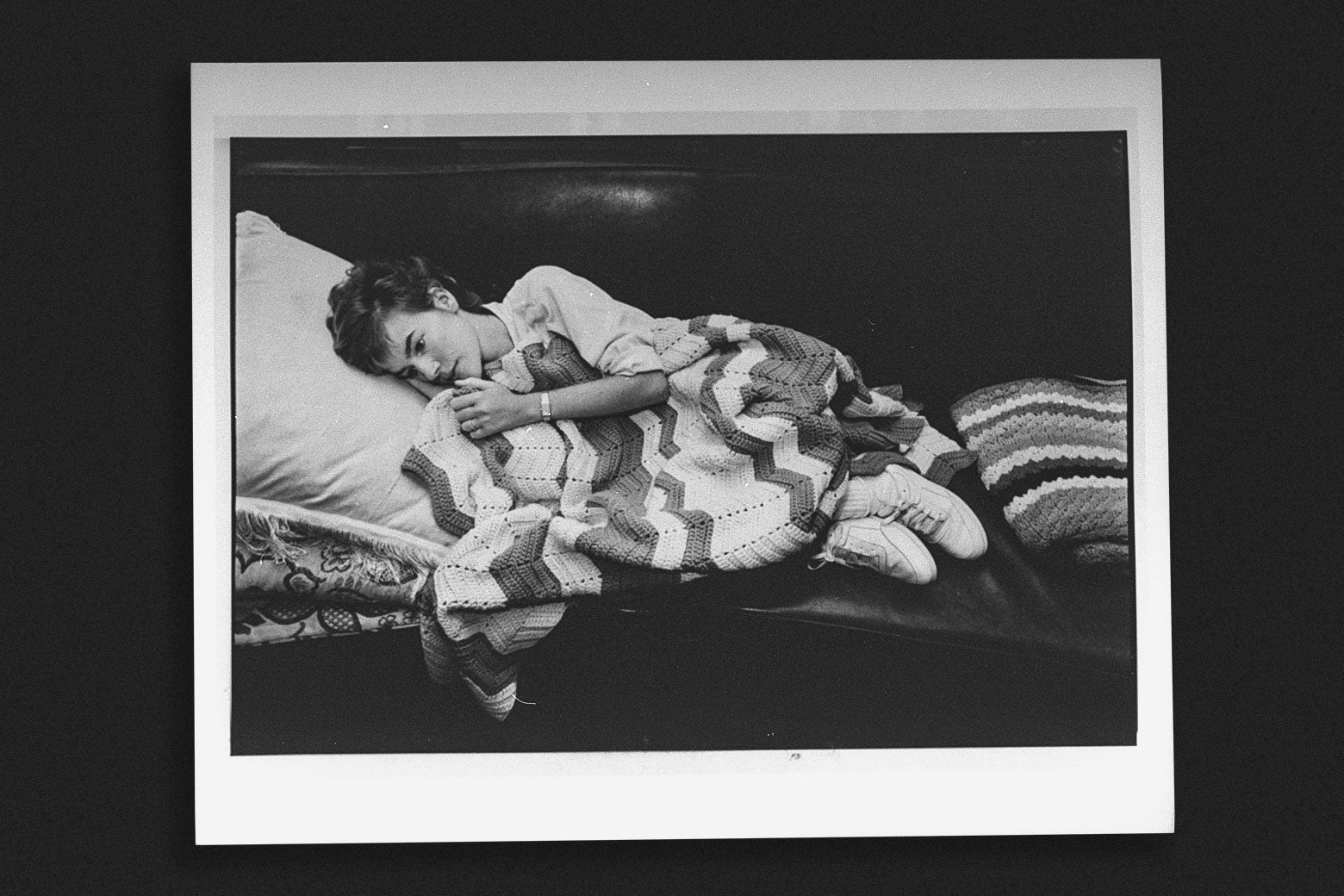

By January 1991, Bergalis had been dealing with AIDS symptoms for more than a year. Despite the medication she was taking, her health was clearly declining. But she mustered the strength to keep on telling her story. On CBS’ 48 Hours, she said that health care workers had a responsibility to tell their patients if they had an infectious disease, “because it’s their life you’re playing with.”

The Bergalis family had made that exact case in a civil lawsuit, claiming that Acer had had a responsibility to disclose that he had AIDS. That turned out to be a winning argument: They got a $1 million settlement from one insurance company and an undisclosed amount from another.

But Bergalis didn’t have much use for money. She was dying. And she wanted to leave a legacy.

Bergalis believed that she was proof that it should be mandatory for health care workers to get tested for HIV.

She wasn’t alone in that opinion. Shoemaker, one of the other patients whose strain of HIV was a close match to Acer’s, agreed with her. “If you are infected or infectious to somebody, you want to watch it, make sure you’re not hurting someone else,” she told me.

In 1991, amid a nationwide outcry over Bergalis’ case, it felt as if momentum were building—that mandatory testing might become a reality.

Although a lot of Americans thought that sounded reasonable, AIDS activists like Barr were horrified. As an HIV-positive gay man, Barr believed that mandatory testing would make the epidemic worse.

“There were a lot of health care workers who refused to touch people with HIV,” he said. “A lot of the health care workers who would work with people with AIDS were gay, so they were more likely to have HIV. So we were concerned that mandatory testing would only make it harder to get health care workers working on AIDS in the first place.”

This wasn’t just a theoretical concern: There were more than a dozen known cases in which an HIV-positive health care worker had lost their job after their status got revealed. That discrimination was motivated by fear, not science. Because when doctors and dentists practiced universal precautions—like wearing gloves and properly sterilizing their equipment—there was almost no risk of HIV transmission. “There were many, many people who had been treated by HIV-positive health care workers, and you weren’t seeing infections, so this was unnecessary,” Barr said.

Bergalis had the potential to change that calculus. Her case showed that transmission was possible. “Yeah, that risk is small,” she said on 48 Hours, “but I’m the one that came down with it. It happens. And it took my life away.”

In that interview, which was broadcast in early 1991, Bergalis sounded like herself. But by the summer, she’d become incredibly frail. At this point, her strongest statement came in a letter released by her attorney. It was directed at the bureaucrats she believed had cast doubt on her story and the policymakers who hadn’t taken action to prevent other cases like hers. And it was incredibly angry.

She wrote, “I blame Dr. Acer and every single one of you bastards. Anyone who knew Dr. Acer was infected and had full-blown AIDS and stood by not doing a damn thing about it.” The letter ended with this postscript: “If laws are not formed to provide protection, then my suffering and death was in vain. I’m dying guys. Good-bye.”

In July 1991, Kimberly Bergalis’ words made it to the floor of the United States Senate, thanks to Jesse Helms. The North Carolina Republican read from Bergalis’ letter. He also claimed, contrary to all evidence, that gay doctors were infecting patients “everywhere” with HIV. Helms said, “We have sat on our hands and bowed to the homosexual lobby time and time again when this senator and others have stood on this floor pleading that something be done about these people who are responsible for the spread of AIDS.”

It wasn’t just Helms. Bergalis’ letter and the cause of mandatory testing also caught the attention of Rep. William Dannemeyer. The California Republican had written an entire book about what he saw as the threat of homosexuality. And in 1991, he’d become the Bergalises’ biggest political ally. Dannemeyer sponsored a bill to mandate HIV testing and disclosure for health care workers. He called it the Kimberly Bergalis Act and asked Bergalis herself to testify before Congress. Despite her failing health, her family accepted the invitation.

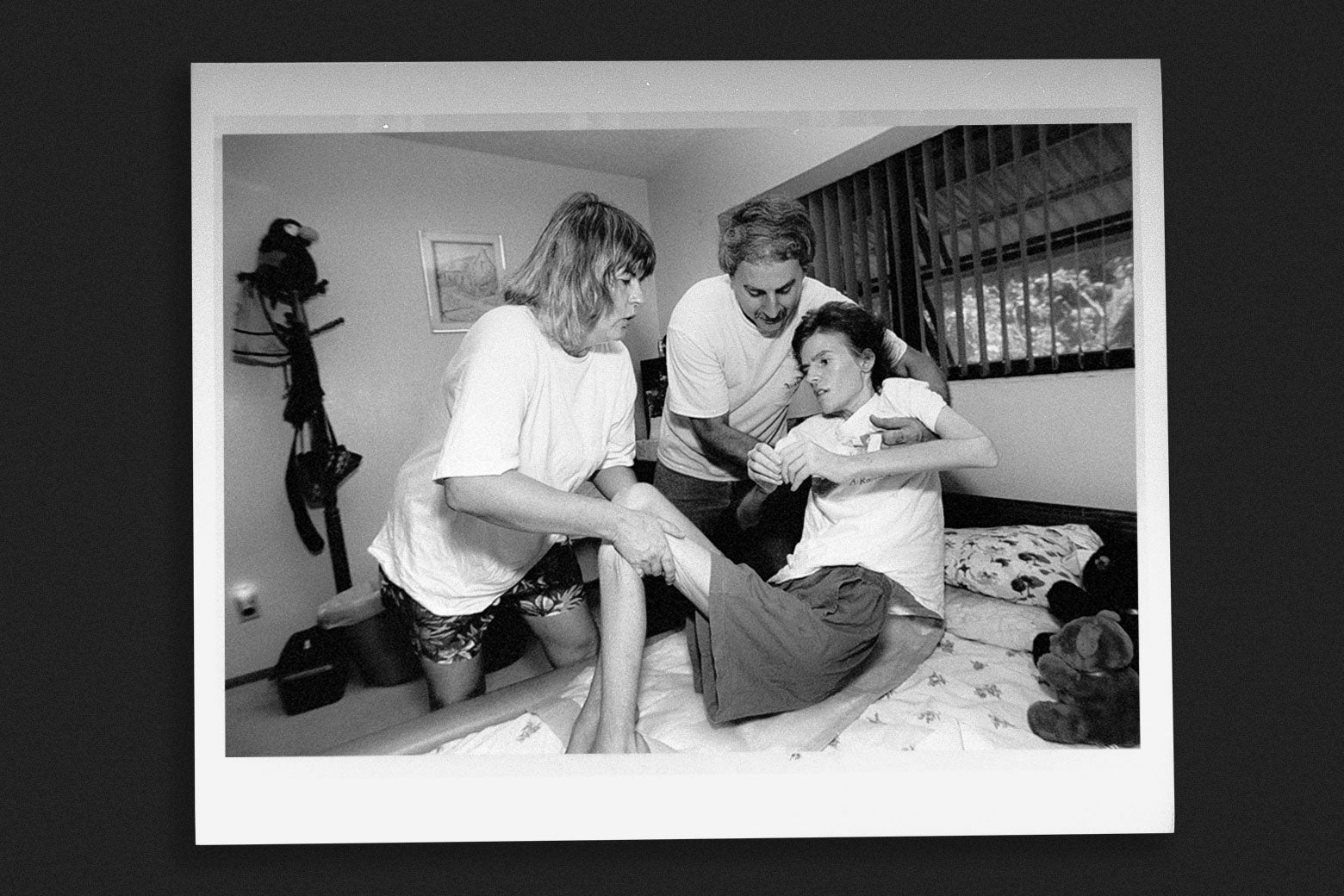

Bergalis traveled from Florida by train, and reporters tagged along to document the trip. At the Amtrak station, her legs were too feeble to bear her own weight, so her parents held her up between them.

In Washington on the morning of Sept. 26, Bergalis was wheeled into a hearing room. She spoke for just 21 seconds, asking for Congress to “please enact legislation so that no other patient or health care provider will have to go through the hell that I have.” Her father spoke next, for significantly longer than his daughter.

He said that Bergalis was “America’s shame.” He said that the civil rights of health care workers weren’t his concern—that legislators “were put here to represent the majority of the people, not the minority of the people.” And he dismissed the claim that mandatory testing would be incredibly costly while saving few lives. He asked: “Does that type of logic mean if Adolf Hitler had been responsible for only a handful of Jewish deaths, it would have been acceptable?”

When her father finished reading his statement, Bergalis was wheeled out of the room. And with that, most of the press cleared out. But the hearing wasn’t over.

Barr, of Gay Men’s Health Crisis, was also in the room that day, to testify against the Kimberly Bergalis Act. When it was his turn to speak, he said that “no other case of AIDS has received more attention than that of Kimberly Bergalis.” He told the politicians that he and Bergalis actually had a lot in common: They were both young and spoke their minds and had family and friends that cared for them. Then he talked about something else they shared: their anger.

“I appreciate and share your anger, Kimberly,” Barr said. He continued, his voice rising:

Like you, I feel that I do not deserve this fate. Although we may have acquired this virus in different ways, I have never asked for this. And neither did over 115,000 Americans who have already died. I am angry that our government will criminalize health care workers instead of allowing them to do their jobs. They will test patients instead of providing care. They will collect names instead of providing treatments that could save our lives. Yours and mine, Kimberly. Here we are, together at this circus, being pitted against each other. Do not allow your case to be used as a means to draw attention away from the real threat that we as individuals and as a nation face from AIDS.

Kimberly Bergalis died at home in Florida a little more than two months later. She was 23 years old.

In her final days, she had gone to Washington to try to spur Congress into action. But the Kimberly Bergalis Act, which faced enormous opposition from medical groups and AIDS activists, never made it out of committee.

In 1991, the CDC issued new guidelines suggesting but not requiring that HIV-positive health care workers notify their patients. (Today that recommendation is no longer in effect.)

In the process of reporting out this story, I reached out to the families of David Acer and Kimberly Bergalis but didn’t hear back. We’ll likely never know with absolute certainty whether Acer transmitted HIV to Bergalis and five other patients. But more than 30 years later, there’s no alternative theory that holds up to scrutiny.

And then there’s this: Since Acer, there hasn’t been a single documented case in the entire country of HIV transmission from a health care worker to a patient. If he did infect those six people, the CDC never could figure out how.

Four of the six patients whose strain of HIV matched David Acer’s died of AIDS within just a few years. Lisa Shoemaker is one of two who are still alive. When we spoke in 2023, Shoemaker told me she didn’t believe that Acer had ever meant to hurt anyone. “When you get into the health arena, you’re there to help people, not to harm them,” she said.

Shoemaker started volunteering in Michigan schools in the mid-1990s, teaching teenagers about HIV and AIDS. She also served on the board of the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS for four years. “A lot of the men that I got to be friends with would just pass away, and I wouldn’t even find out until I’d got to the meetings,” she said. “It was hard, because you’re still here.”

Barr is still here too, three decades after he got his diagnosis and testified against the Kimberly Bergalis Act. Antiretroviral therapy, pioneered in the mid-’90s, has extended lifespans far beyond what seemed possible at the height of the epidemic. But Barr refuses to get complacent.

There are still more than 30,000 new HIV infections in the United States every year, mostly among Black and Latino gay men who have no access to HIV services. “There’s no reason other than willful neglect,” Barr said. “Everything I said to Kimberly about the things I’m angry about is as true today as it was then.”

Sign up for Slate's evening newsletter.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·