It’s not bots writing the news. It’s the bots reading it.

Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

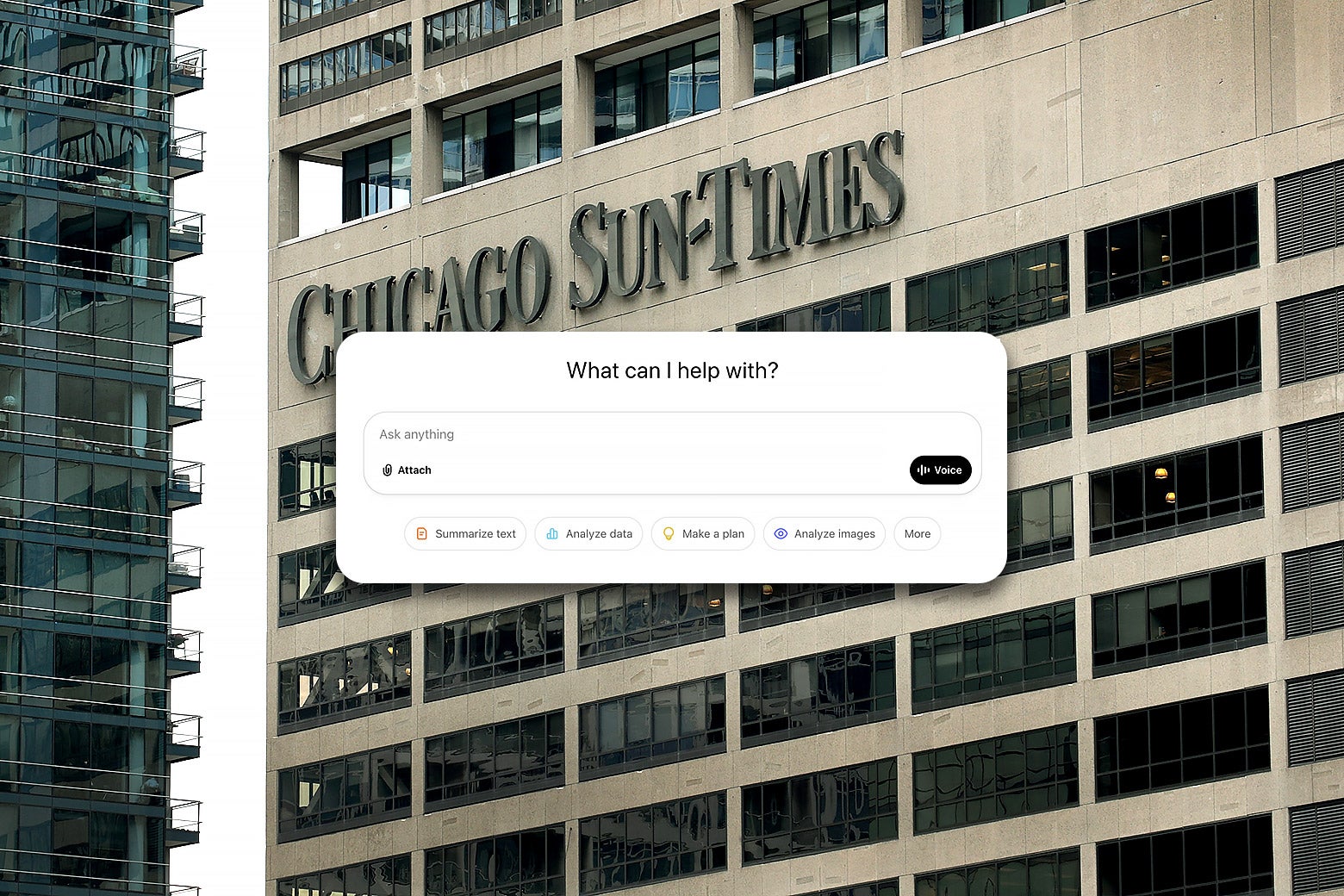

Over the past week, at least two venerable American newspapers—the Chicago Sun-Times and the Philadelphia Inquirer—published a 56-page insert of summer content that was in large part produced by A.I.

The most glaring evidence was a now-notorious “summer reading list,” which recommended 15 books, five of them real, 10 of them imaginary, with summaries of fake titles like Isabel Allende’s Tidewater Dreams, Min Jin Lee’s Nightshade Market, Rebecca Makkai’s Boiling Point, and Percival Everett’s The Rainmakers. The authors exist; the books do not.

The rest of the section, which included anodyne listicles about summer activities, barbecuing, and photography, soon attracted additional scrutiny. Dr. Jennifer Campos, a purported professor of leisure studies at the University of Colorado and authority on “hammock culture” on college campuses, did not appear to exist. Other experts cited on summery subjects like gardening and bonfires were similarly difficult to track down, and some real people whose prior remarks were cited did not appear to have said the things attributed to them. It was a sprawling, newspaper-length hallucination of ChatGPT.

It’s not the first time that a prestigious legacy publication has been caught farming out content to A.I., but for the sheer brazenness of its made-up summer book section, it may have set a new bar.

The section was provided to both papers by King Features, a division of the newspaper and magazine giant Hearst that syndicates special sections, comics, puzzles, and so on. Many newspapers have long relied on such collaborations to fill out their pages, whether the syndication is war reports from the Associated Press or Popeye comic strips. In this case, a comms person at Chicago Public Media, which owns the Sun-Times along with local NPR station WBEZ, told 404Media that they don’t typically vet those products independently because of their source: “We falsely made the assumption there would be an editorial process for this.”

The section’s sole byline, from a Chicago writer named Marco Buscaglia, appears on nearly a dozen articles. When I spoke to him on the phone on Tuesday morning, Buscaglia was contrite about his mistakes, but not his methods. “I have kind of accepted the fact that if somebody wants 60 pages’ worth of stories, there has to be some sort of compromise. But it should be a good compromise. It should be an ethical compromise, and an obvious compromise. And I blew that.”

Buscaglia’s profile is interesting because he’s not a tech guy trying to automate journalism jobs. He’s a 56-year-old media lifer with two writing degrees trying to automate his own freelance job, using A.I. to maintain an impossible human workload of low-paid gigs. He’s the victim of the previous downward spiral of paid writing jobs (thanks to the decline of ad dollars) turned perpetrator of the current downward spiral of paid writing jobs, wielding LLMs to perform a convincing impression of the 25-year-olds who would have crafted the summer heat special section in 1995, and distorting unscrupulous bosses’ sense of what they can get for their money.

And it was a relatively convincing impression. Buscaglia himself did not know about the errors until Tuesday morning, and the Sun-Times and the Inquirer did not issue any remarks until then. (The Inky’s section was published back on May 15.)

The A.I. slop of the Heat Index tells us much about the declining standards of print journalism, but it also holds lessons for the current plight of all journalism. Syndication was popular because it allowed local newspapers to get popular comic strips to their subscribers each morning. The better the comics, the more subscribers, and the more subscribers, the more money in advertising—which, at its peak in 2005, represented more than 80 percent of newspaper revenue. Syndicated games, columnists, and special sections followed in comics’ footsteps.

The fantastical Heat Index insert comprises the dying embers of this business. In its Chicago Sun-Times edition, there’s just one advertisement: for the Goodman Theater’s musical of The Color Purple (unlike the articles, the ad was apparently written by a human, and correctly notes the play was inspired by an Alice Walker novel). Ads were sold for human readers, and most readers are now online—and because the readers are online, an LLM-generated newspaper section persisted for days before someone noticed.

This dual audience for the written word—readers and advertisers—has survived in digital media, and as with silly summer inserts, it’s often the tail of advertising that wags the dog of text. This ad-supported digital ecosystem is the foundation of everything on the internet, news and otherwise, from the business models of Google and Facebook to the popularity of Daily Mail slideshows.

Much attention so far has focused on A.I. wranglers like Buscaglia whose offerings can compete with those of human writers and illustrators. But just as important will be the decline in human readers, as web traffic shifts into robot-to-robot conversations. To the extent a source still wants to talk to a journalist, it may be to influence the results of LLM web-trawling—just as résumés are built by LLMs to be filtered by LLMs, and homework assignments and their grading are simultaneously outsourced to ChatGPT. A feedback loop begins.

An early consequence for journalism comes from Google’s A.I. Overview, which attempts (and sometimes comically fails) to answer questions on the search results page. Some online publishers say the practice is collapsing traffic to their sites, as searchers never follow through to the source of the information, whether on Slate, Wikipedia, ESPN, or IMDB. Users who ask questions inside an A.I. interface like ChatGPT may never see any other piece of the web at all. And who will buy ads if all that surfing is done by an LLM, not a human?

At its developer conference on Tuesday, Google announced it would roll out an “AI Mode” option in every search that will relegate much of today’s browsing experience to the back end. The Verge summarizes this shift:

“Over time, Google seems to think of AI Mode and AI Overviews, and by extension Search as a whole, not as ‘some text summarizing search results’ but something more like a blank canvas for sharing information. Should some results be AI-generated videos or podcasts? Or automatically generated charts and graphs, which AI Mode can already create for you? What about a full, one-off web app, created by Gemini, just to help you answer the question you asked? What if, instead of just offering you some information about your question, Google could tap into Project Mariner and just go solve your problem for you? That’s the future of search results, Google thinks, and it doesn’t have much use for a page full of blue links.”

Project Mariner, by the way, is a Google A.I. product that performs online transactions, such as buying baseball tickets or ordering groceries. Also on Tuesday, the company announced that Mariner will be available as part of a $250-a-month A.I. subscription plan.

In his Stratechery newsletter, Ben Thompson lays out a potential vicious cycle in which a decline in human web traffic prompts a decline in human web creation. The current digital ads ecosystem “depends on humans seeing those webpages, not impersonal agents impervious to advertising, which destroys the economics of ad-supported content sites, which, in the long run, dries up the supply of new content for AI.” A.I. can supply answers to questions because it has been trained on countless copyrighted sources of information, which is the subject of ongoing litigation. If it’s bad at writing true information, it’s because it is also bad at “reading” it.

Which brings us back to the Heat Index. If you Google another one of the Heat Index’s fake books, The Last Algorithm by Andy Weir, you get an Amazon page for The Last Algorithm by Isaac Asimov—a Kindle-only product from February fraudulently advertised as a work by the late science-fiction great who died in 1992. If you Google the LLM-hallucinated hammock expert Jennifer Campos, the first result is the Inquirer insert. Fakery is encroaching.

In some ways, the Heat Index points to where we’re going, toward an internet of regurgitation, in which art and writing are composed of machine-processed fragments of what came before. But the uproar is a sign of something ending—a last gasp from the era of the diligent, human reader who can tell the difference between a real book and a fake one. Our robot readers are not so discerning.

Sign up for Slate's evening newsletter.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·