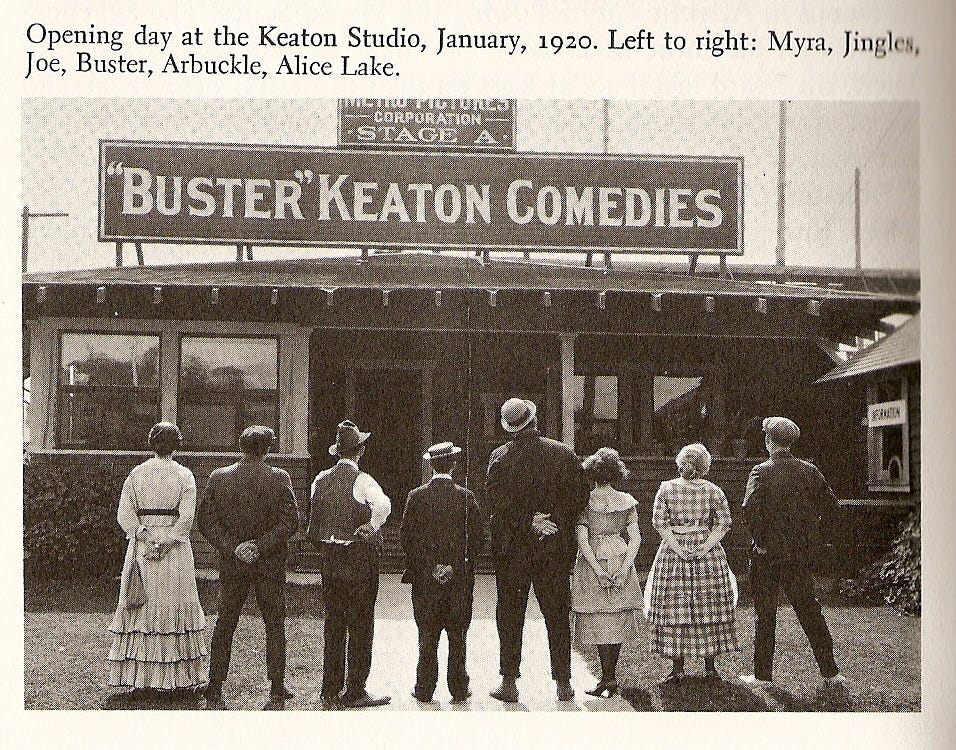

While discussing my tendency to do endless research with zero output, Mills alluded to an unpublished post of mine about Buster Keaton, which would have been the culmination of hundreds of hours of watching movies, reading books, scouring articles, and endless, fractal outlining.

I’m largely at peace with the ambitious project never seeing light of day, save for one bit of trivia that I want to lightly brag about, made particularly timely with this weekend’s release of Mission: Impossible’s eighth chapter, Final Reckoning.

This tidbit concerns the previous entry, Mission: Impossible — Dead Reckoning, which announces its climax with a bridge explosion that sends a locomotive careening down into a riverbed. On the side of the train’s engine one can spy a metallic nameplate which reads La Général Rive-Reine. The first half is a clear nod to Buster Keaton’s The General [1] and “Rive-Reine” alludes to a town in John Frankenheimer’s The Train [2]. As I stepped out of the theater I hopped onto Letterboxd, navigated to the profile for Dead Reckoning’s director Christopher McQuarrie, and demanded my nerd points:

That’s right everyone: I, me, was the first one to be weird enough to badger Christopher McQuarrie about this detail. I trust that McQ mentioned my name to ol’ Tom over breakfast, but I’d hate to die knowing that more people weren’t aware of my achievement.

Hopefully one day I will write the full post!

Dead Reckoning’s whole bridge explosion is an unabashed send-up of the climactic shot in Buster Keaton’s The General.

This was an early vision for McQuarrie:

At the start of this movie, I said to Tom, “What do you want to do?” He said, “I want to drive a motorcycle off of a cliff. What do you want to do?” And I said, “I want to wreck a train.” We're enormous fans of Buster Keaton, John Frankenheimer, David Lean, all of these filmmakers who at one time or another had a fabulous train wreck. I thought, I've earned that, I want to wreck one too.

How does one earn a train wreck? I'd hazard that McQuarrie was still riding high from producing and co-writing box office savior Top Gun: Maverick, which heralded the industry’s post-pandemic rebound. “You saved Hollywood’s ass, and you might have saved theatrical distribution,” Steven Spielberg told Cruise. “Seriously, Top Gun: Maverick might have saved the entire theatrical industry.” From pulling into stations to being greatly robbed, trains have always figured into movie history, making them a fitting motif for commemorating Cruise’s reign as monarch of Hollywood.

McQuarrie also believed they had an opportunity to one-up themselves yet again: “I think the energy that went into developing it, designing that, building it, and then making a sequence that justified its existence was probably the biggest challenge of my entire life.” When McQuarrie alludes to Buster Keaton's "fabulous train wreck" I’m sure he’s aware that The General's crash was the most expensive individual shot in cinema history at that point, around $700,000 today. McQuarrie for his effort only managed to make 2023’s fifth most expensive movie, and only the second most expensive featuring a car chase on the Spanish steps, though that's enough to rank in the twenty highest budgets of all time.

One should acknowledge that a significant amount of the expense came from generously paying crew to idle through the pandemic’s long lulls, and in return to aggressively pivot and make the most out of whatever shooting opportunities they could finagle. These conditions explain some of the strange texture of Dead Reckoning: narrative decisions seem to bend around shooting availability; the photography gets too shabby and buried under CGI to meet McQuarrie’s eclectic ambitions; Tom’s face and hair warp and age unpredictably from scene to scene. It certainly feels like The Pandemic Entry of the franchise: simultaneously rushed and overcooked.

Making things worse, sequel fatigue had already plagued 2023’s box office with disappointing results from Marvel, Indiana Jones, Fast & Furious, and the total collapse of DC. With audiences insisting on novelty, the seventh Mission: Impossible launched into the single most cursed weekend on the calendar: one week prior to Barbie and Oppenheimer. Even then Cruise managed to come in fourth below quasi-sensation Sound of Freedom, and by the end of its run the movie was seen as a major disappointment.

McQuarrie and Cruise made a big display of supporting Barbenheimer, and I believe their enthusiasm for the industry genuinely trumps the ego they have about their own film. I recall McQuarrie in one interview comparing Nolan to Babe Ruth with the tone of inborne generational talent, capable of calling home runs with superhuman ability. While nakedly commercial, Barbie nonetheless communicated an auteur’s vision and both films clearly nourished audiences that had grown sickly from the spread of Cinematic Universalism.

There is, always, a bitterness to McQuarrie’s tone even when complimentary. I find it extremely relatable, particularly as he’s prone to diatribes about how little he cares for critical success or peer respect, favoring himself a man of the people (yet also a deeper student of history than the supposed authorities). He frames many creative trade-offs in terms of critics versus crowds, and I imagine him frustrated that Nolan and Gerwig both “got away with something” that summer.

As a card-carrying Buster Keaton advocate, I’m disappointed that I can’t whole-heartedly recommend their tribute. But taken in a metatextual light, Dead Reckoning summoning the spirit of The General may turn out to be tragically appropriate. The General was seen as a production boondoggle with Buster’s ambitions shooting way past initial budgets. Audiences showed up for it, but given the exorbitant expense Buster’s financiers and producers began clamping down. The General was Keaton’s eighth feature and it would be his last with that degree of total directorial authority. Accustomed to being a hybrid director–star–producer–writer–editor, Buster would only make four more films before studios would reduce him to acting roles only, never getting another chance to direct a feature.

Taken together, Dead Reckoning and Final Reckoning are rumored to have cost something like $700M and many seem doubtful the second film’s performance will justify the whole ordeal. McQuarrie would prefer we cast the films in a broader light: “What everybody misses is that Mission: Impossible movies are classic in their tone and their storytelling. You’re going back to the ‘30s and ‘40s, so as [new people are] coming in with really edgy and modern stuff, we’re saying, ‘But that's going to be relevant for a year. We’re not making a movie for 2018, we’re making a movie for forever.’ The studio’s always going to make a movie for right now. They’ve got a bottom line: what do the kids want? And my attitude is: those kids are going to be thirty someday, and they're gonna be fifty, and then they’re gonna have kids.”

Even the contemporary chatter around Dead Reckoning’s middling performance was overstated as movies of this sort bring money in waves. While The General marked Buster’s permanent downfall at the time, it’s now considered by many to be his magnum opus, sitting 18th in the last AFI list of 100 greatest American films. It’s a permanent presence in silent film festivals, connecting with generation after generation with no sign of losing steam. A movie’s initial place in culture is not always where it stays, and a train wreck now may not be a train wreck forever.

John Frankenheimer’s The Train receives much less critical veneration than any of Keaton’s or Lean’s traincore, and the way Frankenheimer discusses the project is starkly ambivalent:

The Train was a film that I had no intention of ever doing. There was another director on the film and he'd been shooting for about two weeks and he left. I don't really know to this day exactly what happened. There was a conflict of personalities, a conflict over the type of film being made. […] I was quite tired. I didn't want to do it, yet [the producer] asked me to do it as a favour to him. […]

On the way I read through the script. It was delivered to me just as I got on the plane. I thought it was almost appalling, neither fish nor fowl. The damned train didn't leave the station until page 140. When I arrived in Paris we shut down the production and we re-wrote the script.

Christopher McQuarrie has been the de facto Mission: Impossible director since chapter 5, but his franchise start came as a screenwriter when he dropped late into the troubled production of M:I 4 – Ghost Protocol to help put the movie back on track:

My first week was spent just absorbing the movie: watching all the footage, looking at all the sets. What sets have been struck? What sets have not been built yet? What roles have not been cast yet? What can I cut? What can I change? What is in stone? In six days I consumed a movie they’d been shooting for ten weeks and prepping for months before that.

Frankenheimer describes the chaotic environment of completely revamping The Train in the middle of filming it:

It was done absolutely, completely on location, and our problems were enormous, because nobody knew what they were getting into. Nobody knew what kind of film they were going to make. And by the time we really got the script rewritten (of course, it was never completely finished because as we were shooting we kept re-writing) and went to the locations that had been chosen in Normandy, the weather proved to be impossible.

McQuarrie found himself in a similar scene:

When Jeremy Renner grabs that briefcase and he’s gonna throw it out the window, that scene was written that morning and they started shooting it that afternoon. In between takes he’s freaking out because we’ve totally thrown out his backstory… which he’s already shot. He’s like “I’ve been acting for half a movie, I was this other character!’ And I was like, “It’s all gonna be fine, I’ve watched all your footage, it’s all gonna work!” I’m in the bedroom lying on the bed and the AD and the line producer are sitting at my feet and I’m writing, and Brad Bird’s video village is right next to me, so I’m sending them the pages that they’re going to be shooting for the next 9 days. It’s like a movie factory, all this stuff is happening at the same time.

Both men had to improvise a compelling story within the confines of the many production details that were firmly locked. Frankenheimer narrowed in on a premise that mirrored his own ambivalence towards the project:

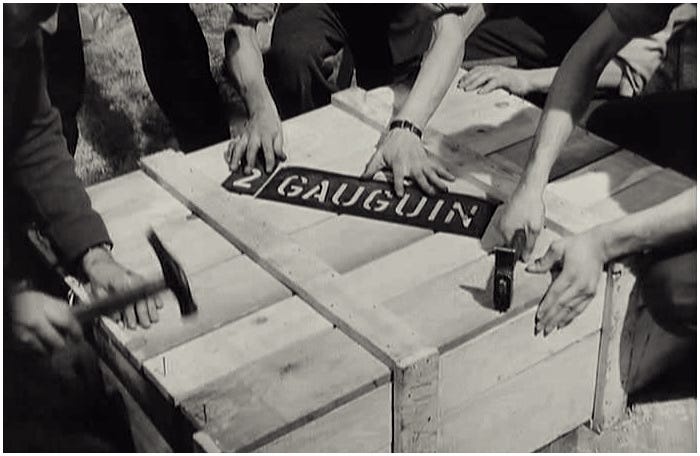

I wanted to include a point of view which I felt strongly about. The given subject matter, which I couldn't change, was this: there was a trainload of paintings the Germans were trying to get out of France before the Allies arrived in Paris. The French didn't want to lose them. The point I wanted to make was that no work of art is worth a human life. That's what the film is about. I feel that very deeply.

In The Train Burt Lancaster leads a French Resistance cell in intercepting a Nazi locomotive carrying priceless works of art by the great masters. At every step Lancaster resists the premise, held by the Resistance and Nazis alike, that these paintings and statues would be worth the inevitable casualities. Despite emerging victorious, Lancaster ends the film racked with regret over the lives lost. Frankenheimer continues:

But to say that the film is a statement of a theme like that is really being unfair (to the film) because in my opinion it is a good action movie, which, incidentally has something to say. I don't think it's a film that you have to read a great deal of social significance into, but it is true to people and their environment. The point that so many people overlook is that in the lives of people, what they do and how they think, feel and behave, is in itself important. If you can recognise the validity of their lives, this is important too and you can show this in a film which is on the surface an action story. Honesty and reality are reflected in people's attitudes – without individuals having to perform great deeds or being great heroes or villains proclaiming great messages about life. It's just that you can recognise life. The Train is this kind of movie.

My favorite sequence in The Train:

McQuarrie similarly aspires to “recognize life” in resistance to the moralizing urge: “Movies are reflections of things. You don’t want me telling you what right or wrong are.” Indeed, his great triumph in rewriting Ghost Protocol wasn’t some profound textual commentary. In his telling, McQuarrie diagnosed the problem as a failure of story–action integration caused in part by the mystery boxes that J.J. Abrams had left in his wake:

I’m of the philosophy that you cannot have exposition during an action sequence. The stakes have to be established. What happens in certain movies you’ll see they’re throwing their exposition at you during the action. There’s no confidence in the writing or in the action sequence itself. They’re basically baking broccoli into your brownies to try to get you to eat the broccoli. Just get the vegetables out of the way, I don’t want to taste broccoli in my brownies! And that was a lot of what I was doing, taking the mystery elements out and creating a narrative drive so that you were just doing a lot less work to watch the movie.

McQuarrie talks like a mechanic, but lore and stories from the crew tell a more dramatic account that would explain the blood brotherhood he’s forged with Tom Cruise. According to the cinematographer Robert Elswit, for more than half of production the ending planned by the studio included Cruise's character moving into a senior role, handing the franchise over to a younger squad likely helmed by pre-app Jeremy Renner. This all changed after McQuarrie arrived:

The guy who has the best version of this is Chris [McQuarrie] and someday, when he writes his memoirs 40-50 years from now, you’ll be able to read about the inside true story of how Tom Cruise took a movie in which his character ends up being booted out of the franchise, how he took that movie and turned it into re-upping the franchise, taking over the movie, taking over the franchise, and starting it all over again.

Fittingly, the textual and metatextual turn happen in a train scene, wherein Ethan Hunt informs the team they’re scrapping all of their original mission orders. Elswit continues:

Essentially what happens in the train scene, it’s a literal and metaphorical Tom Cruise take over. He takes over the IMF crew, and he takes over the movie — that scene does both. And he walks through and he says, “Okay, here’s what happened up until now, and here’s what you’re all gonna do.” He lays the whole thing out, and the rest of the IMF team sits there and goes with it. Chris and Tom created this, you know, “Here I am, I’m back, and you got me out of prison, and we’re not going to do that other script you read when you signed on. We’re doing this new script and here it is.” That is kinda the most inside baseball version of it that I could possibly tell without screwing it up, but that’s what happened.

McQuarrie dances around the particulars when asked:

There was another ending to the screenplay that the studio wanted that no longer fit on the movie. It was more to their liking, but the script that I had written took the movie in a direction that didn’t allow that. […] The studio wanted their ending and they were doing everything they could to somehow make that work, but by the time they arrived we’d already shot all the things that directed the movie where it went and not where they wanted it to go. […]

Mission has a mind of its own. When you start to align the pieces and obey the narrative, you discover it doesn’t matter what you want Mission to be, this is where the movie is going.

McQuarrie often speaks of his process with a self-sacrificial tone, yielding to the forces of the film itself and obeying the logic that it demands of you. While discussing other directors who have struggled with working on the franchise, McQuarrie dug in:

They didn’t want to “make Mission” they wanted to “make Mission theirs.” I have no interest in making Mission mine. To really be honest I think the most toxic thing you can think about as a filmmaker is posterity. I’m in a unique position of being a guy who parachutes into movies and helps them get back on track. One of the things that messes up movies is a director not wanting to do things because of their “perception of their brand.” When something is the right thing to do, it's like: this is where the movie is telling you to go. So I don’t care how I will be perceived in the history of film. I care that my film works, and I care that my film works forever. […] It’s not the award I’m after in a movie like this. I want repeat viewings. I just want people to watch this movie. The thought of making a movie this big and putting so much of your life into it and thinking that the majority of the audience will watch it and go “eh” and never watch it again… the disposability of a movie this size is terrifying to me. The other stuff, it doesn't matter.

While it may have been an act of humility on McQuarrie’s part, the practical consequence is that Ghost Protocol flipped from a denouement for Cruise into something of a keynote announcing a new golden era of his star power. Given that Tom at this moment was between bombs Knight and Day and Rock of Ages, McQuarrie was taking a long bet by doubling down. [3]

This isn’t to minimize the role of director Brad Bird, who has resisted characterizations that the film ever had anything less than total commitment to Cruise’s stardom. Undeniably, Bird’s slapstick sensibilities (Iron Giant, Incredibles, Ratatouille) were the ideal embellishment for Tom Cruise's full-body overcommitment. There's a clear “kinetic storytelling” lineage from silent action figures like Keaton and Chaplin to the vocabulary of cartoon animation that applies wonderfully to the contemporary action genre. Bird set a vision to make a Mission: Impossible movie where “everything breaks” and the film's relentless undercutting of Cruise is crucial to getting a skeptical viewer, like me, to fall for his charms. I mostly don't like Tom Cruise at all, which I realize this post might not imply, and Ghost Protocol got me to crack open.

The movie’s strongest piece of evidence for the Cruise case is the remarkable Burj Khalifa sequence. It’s arguably still the best individual set piece in the franchise’s history. While stuntwork had come in and out of prominence over the series, the Burj cemented into the M:I formula that every movie and its marketing would henceforth be built around a tentpole feat that everyone would know Tom Cruise really did, like, for real. When John Frankenheimer remarks that “no art is worth a human life” one wonders what it means, then, to dedicate your entire life to making art as he did. When McQuarrie takes similarly nihilistic angles on his own work, I can’t shake how many years he’s given over to directing the least nihilistic man alive, Tom Cruise, in a film series premised on risking one’s life, again and again. [4]

Mission: Impossible has always been a vanity canvas for Tom Cruise, the first entry serving as the inauguration for his personal production company. Until Top Gun: Maverick, Cruise turned down all sequels as a policy, save for this personal exemption. The early entries served as a flexible venue for Cruise to collaborate with his dream teams. For all the commercial sheen we associate with Tom Cruise, his career choices before the McQuarrie era seemed largely driven by a desire to submit to as many of the greatest auteurs as he could.

Brian de Palma is certainly not a bland choice to kick off a franchise that now competes against A Minecraft Movie for the PG-13 set. His Mission: Impossible makes the shocking choice to surround Tom with a large team of memorable actors only to kill them all in the first act. It blew my mind when I saw it in theaters at age 10 but now it plays like the original sin of the series. The Mission: Impossible show from the '60s was an ensemble work at its core, partially due to lead Steven Hill's unavailability on the Sabbath. Cruise, on the other hand, had his crew murdered and centers the rest of the movie on his character (who does not exist in the original show) as he hunts down his mentor (the protagonist from the original show). Arguably worth it to own that theme song?

“The genius of Mission: Impossible is that it was clever. Tom always wanted to make it the smartest movie possible,” said de Palma. To that end, Cruise worked on the story with Sydney Pollack, then Steve Zaillian (Schindler’s List) then David Koepp (Jurassic Park) then Robert Towne (Chinatown). With all that brain power, the production began without a complete story and only the set pieces worked out. Given how iconic Cruise dangling from the ceiling became — it’s more or less generic movie shorthand at this point — it's no wonder that a complete screenplay isn't seen as a necessity for these movies.

As maligned as John Woo’s second Mission: Impossible film is, and by no means “the smartest movie possible,” it remains an exciting display of a visionary taking a big swing, and Cruise’s highly-marketed free solo climb can’t be ignored in the lineage of M:I stuntwork. With M:I 3, the thing you must always grant is that Philip Seymour Hoffman gives the series its most robust villain performance. But symmetrically, J.J. Abrams fails wildly in his attempts to humanize Tom Cruise, asking us to believe he could ever retire from work (?!) in order to enjoy a relaxed marriage (?!?!).

When McQuarrie was dropped into the fourth film, Ghost Protocol, one of the largest changes he made was to rewrite how his family was handled. In the story that McQuarrie encountered, Ethan Hunt's wife had been killed prior to the events of the film, inevitably haunting the movie’s otherwise lighthearted tone. Reversing course on the domestic vision for Cruise’s character was the right instinct, so McQuarrie kept her alive while justifying their permanent separation as the combined result of her personal safety and his fealty to a higher purpose.

It’s a hallmark of many great action movies that the male protagonists have wives they love dearly but have no practical obligation towards. The simplest angle is for the wife to be dead, but keeping them at a distance for their own safety is a classic. Despite that, it still took McQuarrie a minute to figure out that audiences have bigger and more specific problems with seeing Tom Cruise interact with women. It'd be their next collaboration, Jack Reacher, where he'd be forced to confront it.

After Ghost Protocol's fictional and literal jailbreak, Cruise reciprocated by offering McQuarrie his own chance to escape “director jail,” in McQuarrie’s words. Jack Reacher would only be McQuarrie's second time directing, a fact that might surprise a film dork from the ‘90s that would’ve known McQuarrie as the promising writer behind The Usual Suspects. It was his follow up and directorial debut The Way of the Gun that earned him his jail sentence. I was 14 when that movie came out and I saw it twice in theaters and multiple times at home after, probably the only age range where one could plausibly want to soak in that much aggressive nihilism (and boy did I). The movie flopped with non-me audiences and critics alike, closing doors on McQuarrie for years to come but producing a plight that would ultimately appeal to Cruise’s sympathies.

McQuarrie discusses the gravity that emerged while they worked together on Reacher:

There’s what you want in the movie, and there’s what the movie wants. We had a kiss with Rosamund and Tom and the audience flatly rejected it. They just said, “No.” And you thought, well geez, I thought that’s what audiences wanted, they want that tropey movie stuff. They just rejected it. They didn’t want it, even though that’s what the rules said.

One might expect McQuarrie to know Tom is a rule breaker? They did seem to apply the main lesson: audiences do not like to think about Tom Cruise having sex. Far more palatable is a woman threatening to outcompete him, like Emily Blunt’s Sgt. Rita in Edge of Tomorrow, the next Cruise–McQuarrie pairing after Reacher. They immediately redeploy the dynamic in the following Mission: Impossible chapter, Rogue Nation.

Rogue Nation’s major contribution to M:I is certainly the introduction of Rebecca Ferguson’s Ilsa, a woman of the same character class and XP level as Tom’s Ethan, but relieved of standard sexual tension as McQuarrie smuggles the will-they-won’t-they dynamic into espionage terms of allegience and blackmail, wherein we find ourselves rooting for them to be great coworkers more than anything else.

Two missteps follow: the second Jack Reacher entry that felt like the eighth, and the aborted cinematic universe seedling The Mummy. Despite the stumbling, Mission: Impossible had now delivered the goods twice in a row and the hype going into Mission: Impossible — Fallout felt like a sea change to McQuarrie:

Tom does not come without his share of controversy and that’s an element of these movies. […] I watched [the most critical] segment of the audience just eventually go, “Alright fine, I’ll come to the damn movie!” They’ve reconciled in a way. I feel that in this movie. This is the first time of the nine movies in twelve years where I really feel the wind at our back. […]

There was a perception for a long time that Tom was doing what he was doing for his ego. No, he’s really killing himself for your entertainment. He really loves making movies. He loves nothing more than the process of sitting in the audience and watching the movie with them. He goes to every test screening. He reads all the cards. Everything you’re saying about Tom Cruise, he’s read it and it’s water off his back.

McQuarrie’s reading here of Tom Cruise as “killing himself for all of you” is fully realized in the text of M:I Fallout. McQuarrie describes setting the tone in the opening:

What was important to me was this sense of, “What does Ethan do when he’s not on a mission?” In Mission 2 he goes on vacation and climbs a mountain. The image that I wanted is that, when Ethan woke up, there is this sense of real loneliness and an empty life.

Fallout's emotional stakes turn on the inescapable reality that anyone who gets close to Ethan/Tom is placing themselves at risk (especially whoever marries him), yet the entire world/Hollywood needs Ethan/Tom and we must tolerate his dangerous aura and chaotic methodology. McQuarrie is not subtle about these metatextual aspects of his movies:

We always look at it as: the making of a Mission: Impossible movie is very much like watching a Mission: Impossible movie, and we laugh all the time that your job on a movie is the studio says, “Here’s your mission, go do it.” And as you’re doing it the studio goes, “Are you insane?! You can’t do that! They’ve gone rogue!” And you of course do go rogue and you violate a lot of the laws that you've agreed to, and then the studio is constantly looking at you like you’ve gone off the rails, and you’re going to destroy the world! And then, when it’s over, everyone is like, “Hey! Mission acccomplished! Let’s do another one!”

As a collaborator gossiped, “Tom says what he wants and the studio says what it wants. And then Tom gets what he asked for.” Throughout all of the M:I films, Cruise’s character spars with a revolving door of bureaucrats, stand-ins for the studio executives who constantly seek to control a process they don’t understand. In Fallout, Henry Cavill’s arm-reloading villain begins the story as Ethan’s ally, and their conflict initiates over working methods when Cavill’s easy and blunt approach doesn't align with Cruise’s trademark perfectionism.

Fallout’s most impactful statement on studio-driven mediocrity came indirectly, after WB approached McQuarrie about the possibility of shaving Henry Cavill for Superman reshoots happening in parallel. WB argued that the mustache could be restored with makeup or CG, but McQuarrie held firm that anything short of Cavill's natural fur would be unavoidably dreambreaking and enforced their contractual rights to deny the shave. WB, now publicly committed to their estimation of mustache technology, went ahead and removed the hair from their film in post, producing one of the greatest abominations in cinematic history.

Over these long McQuarrie years, Cruise has stepped off the proverbial couch and wisely began limiting his public appearances to promotional contexts, declining to discuss anything beyond movies and keeping to the most banal sentiments ever recorded. “Being friendly doesn’t cost a bean and I enjoy it,” Tom (61) confessed in a rare non-promotional interview with Derbyshire Life. In this way he and McQuarrie successfully renegotiated the boundaries of our cultural relationship with Tom Cruise: a steady withdrawal of his real personal life from the public eye paralelled by a steady advance in his on-screen persona towards autobiography: hypercompetent, earnest, weird, lonely.

By the time the pair arrived at the seventh entry, Mission: Impossible — Dead Reckoning, the Ethan/Tom persona refactor was complete and Top Gun: Maverick had them at the peak of the ‘mount. Beyond the victory lap implied by the train wreck, Dead Reckoning can be taken at name value. The movie seems to be McQuarrie and Cruise wrestling with legacy and finally confronting the Ghost Protocol they’d shirked: what happens to M:I/the IMF after Tom/Ethan?

I haven't seen Final Reckoning, but DR’s story seems to be laying track for Mission: Impossible to transition into an ensemble franchise, undoing the original film's demonic pact. The narrative’s spine follows the recruitment of a new agent, Hayley Atwell's Grace, a world-class pickpocket to whom they offer “The Choice,” a retconned bit of M:I lore that suggests all of the agents, including Ethan, were once highly talented criminals who only became operatives to avoid a life in prison. Given that in every other movie the IMF falls apart from corrupting forces, McQuarrie has to do some gymnastics to convince us there's something substantial for Grace to align with here.

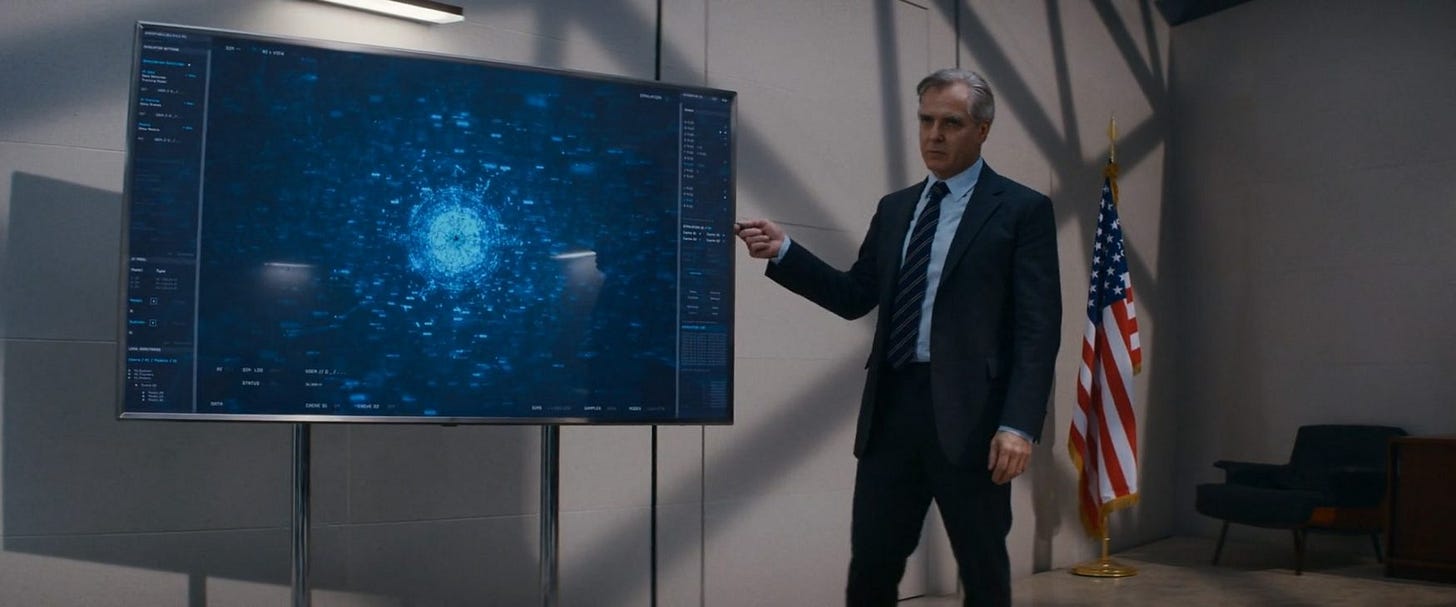

Dead Reckoning’s clearest articulation of the group’s higher purpose comes by contrast with their antagonist, a rogue superintelligent AI named The Entity. The villains in these movies have never had coherent motivations and the move to a non-human is honestly clarifying. The Entity exploits every single modern technological anxiety at once, deploying self-driving cars, deepfakes, catfishing, social media manipulation, autonomous defense systems — it even trades crypto. The hagiographic reading isn't hard to project: deepfakes already threaten the old school filmmaking that Cruise and McQuarrie venerate. Dead Reckoning includes distant flashbacks and the team did run experiments similar to Dial of Destiny’s controversial de-aging of Harrison Ford in that same year. But McQuarrie observed that even when the work is absolutely seamless you're still left thinking, “Wow, well how did they do that?” instead of remaining grounded in the reality of the story.

You don’t want the audience stopping to think. Hitchock’s rule number one: it’s about creating a dream state and maintaining that dream state for as long as you can.

More broadly, technological forces threaten many of the sacred elements of traditional moviegoing: phones and video games competing for time, CGI replacing stuntwork, streaming services choking theatrical distribution. Social media draws special ire from McQuarrie who has railed against fandom culture since Jack Reacher book readers largely rejected their adaptation. “Star Wars was not made for Star Wars fans,” he quips. The bureaucrats, however, do make things for Star Wars fans. In Dead Reckoning, every single instutition in the world aims to acquire The Entity in order to install it back home in their smoke-filled rooms. Elaborating on the themes of Maverick, only Ethan/Tom and his team are clear-eyed enough to resist the temptations of technology.

Many of the new characters in Dead Reckoning have either Biblical names or names from the original show, perhaps as penance for M:I 1. The Entity's human avatar takes the form of “Gabriel” who tries to persuade “Grace” that Ethan is an egomaniac: “You think he cares whether you live or die? He only cares about this objective!” Gabriel accuses Ethan of being “cold, logical, unemotional,” the attributes of The Entity, of course. When Ethan gets his chance to counter, he offers Grace the opportunity to “become a ghost” with them. “When do I get my life back?” she pleads. Ving Rhames steps in to neg her, “What life? I mean it, Grace. What life? I lived that life, we all did. Nobody’s making us do this.” “We're here because we want to be,” concurs Simon Pegg, pushing against any characterization that Cruise lords power over everyone. “Without a team, your life[/movie career] won't be measured in years or even months.” Grace: “You'll protect me is that it?” Ethan steps forward, “No. I can't promise you that. None of us can. But I swear… your life… will always matter more to me than my own.” Grace, tearing up, “You don't even know me…” Cruise closes the candidate and the scene at the same time, “What difference does that make?”

While the American government/studios cannot trust the IMF/Cruise to obey them, they ultimately do trust the IMF/Cruise to work on the side of humanity/audiences — whether that's attractive pickpockets or the international theatrical market. Like Ethan, Tom's Missions depend on the massive resources afforded to bureaucrats, including real heads of state like when negotiating Dead Reckoning’s sequence filmed across an entire empty airport, or the various demolitions made to the Burj Khalifa. He’s the “living manifestation of destiny” as Alec Baldwin describes Ethan in Fallout, capable of channeling the resources that these films demand from the world.

You can find action franchises with better writing, bigger box office returns, or more critical appeal, but Mission: Impossible has remained the gold standard in stunt-driven spectacle. This isn’t a consolation prize. Working the extremes of both physical ability and cinematic scale, in concert, requires a level of destiny/star power/mania that only a few can access. If Cruise and McQuarrie can’t persuade a new generation to accept The Choice, we will risk losing a special class of filmmaking, one as old as the medium itself. [4]

When Tom Cruise fields interviews he tends to speak in the manner of a spergy athlete who can’t resist linking everything back to their craft and their craft back to everything else. His answers can feel more like internal monologue than rehearsed showman:

You know I grew up with Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, Charlie Chaplin, I studied the origins – Lumiere – of cinema, but also of storytelling and how it evolved. How do we create these effects on audiences? These are things that I was always interested in. It’s a journey. It’s something that… the derivation of art is skill — I looked it up, it’s skill — and it’s interesting because I think that I learned early on, as a kid, if I could do this for the rest of my life, if I could become skilled at this, if I could understand for myself and be competent — because my goals were like, how to be skillful in many many things and how do I, everything I’ve learned…

Cruise makes sense of himself in film historical terms and when the early pioneers come up he reliably emphasizes Buster Keaton most of all. Chaplin is certainly the most famous, carried the most artistic credibility, and was the global box office king. While Harold Lloyd was less of an auteur, he was a shrewd collaborator and the domestic box office champion between the three. The popular conception of Tom Cruise would seem to favor either of those comparisons first. So why Buster? The first glaring answer, especially in light of Mission: Impossible, has to be stunt work. All of the silent greats were truly exceptional physical performers, but Buster is incontrovertibly the stunt king.

While Keaton worked train bits into almost every one of his films, The General (1926) represented the culmination of this fixation. It has the total vehicular commitment of Mad Max: Fury Road, down to the elemental "there and back again” spatial clarity. In the silent era, expression through the visual and kinetic was essential when the alternative was the jar and bore of title cards. Keaton and Chaplin traded records for the fewest title cards used in a successful feature, working to translate as much as possible into the purely visual realm. “We’d do anything in the world to break them up,” Buster said.

“Information is the death of emotion,” agrees Christopher McQuarrie. When the Hitchcockian dream state is broken, the audience is reminded of themselves as being an audience, separate from the actor. Nothing could be worse to Tom Cruise who seems to work backwards from this vision of a shared dream, “How do we create these sequences and have the audience actually feel, have physical reactions, when they’re watching something?” He’ll make revealing remarks like, “I want to entertain an audience and I just know it’s going to be exciting for them to do that,” before correcting himself, “to see that.” Or, my favorite, “I’ve always loved an audience, and I make my movies for audiences. Because I am an audience, first and foremost.”

For Tom, stuntwork doesn’t belong to some special category distinct from acting:

Gene Kelly was never asked why he performed his own dances and didn’t use stunt doubles. Why do they always ask me? I took a lot of dance lessons, I fly helicopters, I skydive. I want the audience to experience the most extreme and immersive experience possible.

Mission: Impossible is defined by this ambition, to consistently push the edge of the “most extreme” experience that an audience can have. Accomplishing that takes an extreme personality with extreme talents coupled with extreme resources. I've never cared for Tom Cruise as a character actor so as Ethan Hunt’s persona has converged on authentically weird and lonely, I find myself able to relax and appreciate the genuine physical extremes on display.

From Tom’s perspective, every new spectacle he pulls off isn’t a personal achievement so much as a broadcastable experience, and the crew's concern is to maximize how much of that experience they transfer and how many people they transfer it to. I believe this is the nature of the selflessness that McQuarrie makes appeals to, and it’s a philosophy that reverberates through every level of their process. It can feel absurd to speak of selflessness in the context of the rich and famous making Hollywood blockbusters but in the interest of “recognizing life” I can see how they see a healthy alignment here. The world is powered by positional status: whoever owns the tallest building in the world wants it to be climbed by the most popular actor in the world. There cannot be more than one Tom Cruise at a time, in principle, and the resources that will naturally gravitate towards him ought to be used as selflessly as possible.

By working backwards from audience experience, they bind the natural gravity of Cruise to the natural gravity of a box office that eventually gets weary of weird, gross, powerful people wasting their time. Megalopolis serves as a contemporary counterpoint, a movie tethered only to the one gravity well of its auteur. Both men clearly live in alien mental states, but Cruise's makes constant contact with the masses. In a time when all movies are discussed against a backdrop of the struggling theatrical business, Cruise has partially won over film nerds like me because he reliably gets butts in seats. I share his romanticism for the movie house, the communal dream state. When Tom sweats the world sweats with him, and I'm basic enough to cherish that connection. When he struggles to maintain a clear separation between himself and the audience, I see someone who has devoted so much of his life to this aspiration that it's become a permanent blur, not someone egoically obsessed with box office numbers.

Buster Keaton in interviews often sounds like Cruise in this way. When asked which feature of his he personally liked the best he replied, “My biggest money maker was a feature picture, The Navigator.” When provoked to think more deeply about his work he just brings it back to the ground of why audiences respond:

Studs Terkel: Now you just used the word, “mechanical,” which brings us to another point. Agee, and his Iris Barry (in this excellent book by Griffith and Mayer), speak of you as the master of what they call “the mechanical gag.” Chaplin in Modern Time was kidding the machine, but there is a difference between the two that Iris Barry points out that I think, if you could expand on this: “Buster Keaton moves in the mechanical world of today like the inhabitant of another planet. He gazes with frozen bewilderment at a nightmare reality. Inventions and contrivances like deck chairs and railroad engines seem… animate… to him, in the same measure that human beings become impersonal. Without friends or relatives, he is generally incapable of associating with his fellow-beings on a “human basis,” but mechanical devices, though often inimical to him, are… the only “beings” who can “understand him”. And then she [Iris Barry] goes on to speak of Chaplin escaping into the realm of freedom in his films, but you actually throw your humanity into the machine world, and you make the machine so much a part of yourself. Could you tell us a little bit about this, you and the machines? The way you work with—

Buster Keaton (interrupting): Well, I guess I found out that I get my best material working with something like that. In other words, I was one of your original “do it yourself” fellas. I may not know how to do a carpenter’s job, but I set out to build a house.

Terkel: And then as you build it, it becomes funnier and funnier.

Keaton: Everybody knows that you are going to get in trouble when you start that.

Many of Keaton’s movies are completely recommendable today, without asterisks for being silent or black and white. By operating visually and kinetically, silent action and comedy naturally moves at a modern pace and still connects with modern audiences. Silent dramas, unfortunately, tend to be slogs of dialog obscured by antiquated social context. Technological limitations have never prevented art from conveying the wholeness of the human condition, and the immaturity of the medium actually worked heavily in favor of Buster’s ability to attune with audiences.

During the ‘20s the industry hadn’t yet congealed into the studio system. Buster owned his own production company which gave him immense autonomy. We tend to think of directorial freedom in terms of “creative control” but this was freedom in a more expansive sense. When conversations get into the nuts and bolts of production, Keaton starts to sound more McQuarrie than Cruise:

Now here's the difference in independent companies in those days. When you owned your own studio and you’re the only company in there, well, you’re making feature-length pictures. Well, you make two a year — a spring release and a fall release. Your skeleton outfit of the company — that’s your technical man, your head cameraman and his assistant, and the prop man, your head electrician — these people, they're on salary with you for fifty-two weeks of the year.

So, if I’m sitting in the cutting room, and the picture's been finished, I’m going through it, and I say: “I’d like to take this sequence out, and if I’d turned to the left in that alley there, I could drop that whole sequence and pick it up right here. So, we'll get the cameras out this afternoon and we'll go back to that alley and shoot it.”

Now, to do that, that’d cost me the gasoline for the cars that we owned and the amount of film that we bought from Eastman to put in the camera, which when it all adds up means about $2.39. You try that at any major studio today, and I'll tell you the least you could get that scene for — just go out and grab that scene and get back — would be around $12,000. Because everything is rented. Every! Thing!

When coordination becomes 1000x harder, the scope of what’s possible is reduced so dramatically than “final edit” feels like a parochial concern.

Keaton and his team had the ability to respond in real time to the movie they were making, able to redirect the track as the terrain became clearer:

Franklin: Could you re-create for us the atmosphere in making these films without a script?

Keaton: Well, when myself and the three writers had decided on a plot — we always looked for the story first — and the minute somebody came up with a good start, we always jumped the middle. We never paid any attention to that. We jumped to the finish. If a man gets into this situation, how does he get out of it? As soon as we found out how to get out of it, then we went back and worked on the middle. We always figured the middle would take care of itself.

Well, by the time we got something all laid out and were talking about it, the head technical man that builds your sets and also gets your locations for you, the head cameraman, the head electrician, the prop man, the wardrobe man — those fellows are on weekly salaries, they're right there in the studio anytime we wanted 'em. They know about as much about what we are going to do as we do. So we'd say, "All right, Gabe, we'll need a set," and we'd take a piece of paper and a pencil and just draw, saying, "put it on that angle, so I can get around out of there quick and get back through there."

He'd say, “All right, we'll fix that and that and that.”

“All right. Where do you think we ought to go?”

“Well, Kernville is a good location for this.”

“Start in Scene One?”

“Yes.”

“Well then, we'll start on location. I'll have the sets here in case of bad weather.”

Well, everybody knew what you wanted, so there was no problem there. You didn't have to have it written down. Now the thing happens to us when we start into production, here we put up this nice living-room set, and right off of it is a broom closet. Well, he made this a very good-looking set because we were going to do a pretty long routine in this thing — it calls for a lot of action. We'd get in there and start to shoot, and find out that it ain't working right. We were going out of our way to make things happen; it's not good, but I found out I got in trouble in the darn broom closet. Well, right then and there I'm liable to spend three days in that broom closet and only half a day in this living room that we've filled with forty-five or fifty extra people.

Well, when a big studio today has got their schedules laid out, and those people are called and everything, you go in there and shoot regardless.

Franklin: No improvising.

Keaton: No. Why, we'd change every other minute. We never knew what we were running into. When we ran into something, we stuck with it.

Franklin: Isn't that what made it great comedy?

Keaton: Sure. That's a great handicap today.

Franklin: No flexibility at all.

Keaton: No, and the minute you're not flexible that way, the desire to originate and ad-lib, as they call it, is gone. You've lost that. You're too damn mechanical.

The absence of sound meant the team could openly talk through the material as they shot it, marking little distinction between rehearsal and performance:

Because half of our scenes, for God's sakes, we just talked over. We didn't actually get out there and rehearse ‘em. We just walk through it and talk about it. We crank that first rehearsal. Because anything can happen — and generally did. And we got our best sequences that way... We used the rehearsal scenes instead of the second take.

Today, and especially since sound came in, they were pretty strict before on rehearsing scenes until the director thought they were perfect before he’d crank. With us, we used to say one of the hardest things in the world to do in pictures is to unrehearse a scene. In other words, you get so mechanical that nothing seems to flow in a natural way. Cues are picked up too sharp and people's actions are just mechanical. Well now to get that feeling out of it is unrehearse the scene, and we generally did that by going out and playing a coupla innings of baseball or somethin'. Come back in and someone’d say, “Now what did I do then?” I'd say, “I don't know. Do what you think best and then go ahead and shoot.” That's unrehearsing a scene. Coffee break or somethin’.

The necessity of improvisation for comedies isn’t so surprising, but this fluidity holds the entire process together. Like McQuarrie, Keaton believed that story and action must work in concert to form a whole. Like Cruise, Keaton believed that action must be both real and extreme. Under these constraints a process converges: throw all of your pre-planning into the setpieces, then give yourself maximum freedom to iterate on the story that surrounds them.

All three also believe in the audience as ultimate arbiter. The shared dream state is an empirical question, and things like audience testing and reshoots weren’t seen as evidence of some failure, but rather the preferred method for tuning the dream machine:

Well, we have never made a picture — I know I never did, and I know Lloyd never did, and I'm sure Chaplin never did — that we didn't go back and set the camera up again. Because we helped the high spots, and redid the bad ones, and cut footage out, and get scenes that would connect things up for us. We always put a makeup on and set the camera back up after that first preview. And generally after the second one, also.

McQuarrie describes the grounding role that audience testing plays in their process:

In the midst of all the pressure and everything that’s going on, you convince yourself that certain things are having an effect that they’re not. We’re better at it now than we were, but we’re constantly stepping back from things, and looking at it and saying, “Forget what I wanted the audience to feel, what did I actually communicate? What does this frame actually say? Where is the eye actually going?”

Keaton didn’t see testing as limiting or a mechanism of studio control, at least not initially:

And we don't tell the audience they're lookin' at a preview. See, we want a cold reaction. […] Our system was not lettin' the audience know so that the audience wouldn't “yes” us.

The minute you got in one of the major studios — oh, I fought my head off at MGM when I went there — and find out that they ballyhoo it. So that you got the audience in there, the minute it says, “MGM Presents,” the audience applauds. And different characters come on the screen, they applauded 'em. They applauded the director's name, they went out of their way to laugh at things that the normal audience didn't laugh at.

They yessed the life right out of ya. (Laughs) Well, that hurt me. I didn't want that at all. I couldn't stop 'em. Well, that's because workin' at a major studio, all companies are assigned to a producer. Well, the producer wants to make sure that the high brass of the studio sees a good picture even at the first preview.

As clearly as Keaton saw things a hundred years ago, still today McQuarrie sees a constant fight to justify this approach:

I said to the studio before we went into [Misson: Impossible — Fallout], I’m not going to write a screenplay until we’ve scouted the entire film. I want to know where it’s all taking place. Because what happens is, you write a sequence in a vacuum — and I learned this from Rogue Nation — there were times on that movie we didn’t know what it was and they kept saying, “What is the end of this sequence?” And I said I can’t tell you because I don’t know where it happens. Find me a cool location. And they said we don’t know what location you want because we don’t know what the scene is. I said: find me a location and I will tell you what the scene is. The location dictates action. I did that with the entire film this time. I started the movie this way. Of course that was even more confusing, because they were like, “We don’t even know what the story is!”

But McQuarrie wants to preserve their ability to listen to what the movie is telling them:

You get tunnel vision. You get caught up in things you think you have to do. And you forget how you got there. So to have moments of clarity in real time while you’re making your own movie and say, “Do we really need this?” As soon as I say “we have to do this” I ask myself, “Why? Why do you have to? Do you have to because of a rule of cinema, or because of a rule you made up. You wrote that rule you can unwrite it.”

Suborning the screenplay wasn’t a denigration of story for Keaton. He understood that narrative underpins everything:

Abbott and Costello never gave story a second thought. They’d say, “When do we come and what do we do where?” Then they find out the day they start to shoot the picture what the script’s about. Didn’t worry about it. Didn’t try to. Well that used to get my goat because, my God, when we made pictures, we ate, slept, and dreamed them!

There is a logic to ensuring a scene works, whether or not it’s always clear when you start. When filming Seven Chances, Keaton describes how he hit on the climatic chase sequence by pure accident:

I led [my pursuers] off into open country and was coming down the side of the hill, and there were some boulder rocks on that hill, and I hit one accidentally, sliding down that hill on my feet most of the time. And I jarred this one rock loose, and it actually hit two other rocks, and I looked behind me in the scene and here come three boulder rocks about the size of bowling-alley balls coming at me, bouncing down the hill with me, and I actually had to scram to get away from them. [...]

Well, this was the only scene of that in the picture but at the preview — the second preview — when this was in there, the audience sat up in their seats and they were ready. I says, “Oh, oh, that's all we need.”

We went back, and for a finish we built fifteen hundred rocks, starting from grapefruit-size up to one was eight-foot in diameter, and we went out on the ridge route and spotted one of those big barren mountains with these rocks and then I went up there and got started. At least I was working with paper maché, although some of them... for instance, that big one weighed four hundred pounds. By the time you built the framework, it weighs something, but you could get hit with them all right.

Well, I got into the middle of the rock chase, and it saved the picture for me, and that was an accident. It hadn't been framed. It was an out-and-out accident.

McQuarrie echoes their dependence on rolling with it:

We describe the development of every action sequence as a pebble rolling downhill and turning into an avalanche. The first pebble was during Fallout and I was scouting Paris and I found this little Fiat Cinquecente parked on a side street. That was where the idea was born, the notion of Tom driving that sort of car in a car chase, I thought would be funny and I had that in my pocket. We knew we wanted to shoot a sequence in Rome but didn’t know what that sequence was. When I was scouting Rome and driving around the city I realized, this is a very difficult city to drive around. Why wouldn’t you want to have a car chase in a city like this? Then the notion of Tom being handcuffed to whoever it was he was in the car chase with. If only to make it that much more difficult having done multiple car chases with Tom at Ethan. What would the next layer be? With that, each notion, as you started to put those together inspired other ideas that inspired other ideas that spawned the sequence you ended up seeing.

Essential to both Keaton and Cruise’s performances is a style of filming that ensures the audience never loses their connection with the actor, favoring long takes in wide shots with the actor’s face in full display. Where Lloyd and Chaplin disappeared behind fake glasses and mustaches, Keaton felt it was critical that people understood it was really him out there and not some stunt double.

In one of his most notorious escapades, Keaton sustained a major injury when falling onto train tracks (what else?) yet managed to remain in character, delivering a wonderful comedic pause as he glares back at the watertower that seemed to attack him out of nowhere. He wouldn’t discover he’d actually broken his neck until years later during a routine physical.

Such disasters often become boons under this methodology. While filming Mission: Impossible — Fallout, Cruise broke his ankle failing to make a rooftop jump, and McQuarrie seized on the opportunity to catch up to the movie they'd shot so far:

We were very lucky that Tom broke his ankle. Because he broke his ankle, we were able to assemble a lot of the stuff we had shot. We spent a lot of time in the editing room. We were cutting ahead of shooting, which is very unusual on a movie like this.

While filming his first feature Three Ages, Buster likewise failed miserably to make a jump across two rooftops. His crew caught up to what they’d made, and realizing how comedically delicious the footage was they waited for Buster to heal up and shot additional gags depicting his entire fall down the side of the building. For Buster, turning mishap into material was nothing new:

Friedman: ’Cause your vaudeville training, I suppose, let you take advantage of that?

Keaton: Sure. We had the most ad lib act in the world. We never did it twice alike in our lives.

The pre-studio system allowed Keaton to treat filmmaking like an extension of his earlier career in vaudeville, reading the room in order to continually refine the tiniest of details. He was star, director, producer, writer — even editor, splicing his own films together by hand:

I always cut my own pictures. [...] We’ve lost that because soundtracks kind of have made that almost mechanical. We used to study frames of pictures for the love of Mike!

Buster resisted studio interference for as long as he could, but it only took two films under his contract at MGM before he folded completely in 1929, never directing another feature again despite living well into the 1960s. It wasn’t a matter of a silent star unable to adapt to the era of sound — his ‘30s talkies all performed well enough. But the entire framework that surrounded him had been destroyed, and acting roles alone would not be adequate for Buster to make truly great movies, or to sustain his love for the craft that he’d worked tirelessly to perfect.

There’s only been one radical change in Hollywood, and that was when sound first came in, because it brought a whole new cycle, I mean whole new factions: songwriters, dialogue directors, stage directors, stage producers. A whole new faction moved into Hollywood, and from then on, for some silly reason, there was class distinction. People who got $500 a week were seldom seen with somebody getting $1000 a week — you'd never see them at their house. Whereas in the old days, it was a common thing for a prop man in our studio to say, “Good morning, Joe,” when the boss of the studio came walking past. We didn't used to have to put policemen on the gates to stop each other from going to the other one’s studio.

Decades later when asked if he’d ever consider returning to directing Buster answered:

I’d go back to my old format — that's the way I made ‘em before. But I have no intentions of doing it. I just don't think it is worthwhile anymore. I think in making a program picture today you're just asking for trouble. You can't get your money back. You've got to make an Around the World in Eighty Days, The King and I, you've got to get into one of those big things in order to get your money back.

Cruise and McQuarrie find themselves in the same bind today, pinned to a franchise that demands planet-wide success to justify its continued existence. How many times can one man one-up himself at this scale? In Buster’s case we never learned the answer. He was ready to put his entire life on the line for us but we only got to witness his first act.

In Dead Reckoning, Ethan Hunt narrowly avoids following La Général Rive-Reine down into the wreckage, and Tom Cruise may remain our best hope for carrying forward Buster's tradition of chaotic stunt-spectacle filmmaking. “I’m going to make movies into my 80s; actually, I’m going to make them into my 100s,” Tom declared while theoretically promoting his “Final” Reckoning. I do believe that Tom intends to give himself to us until he dies, but given the peace that Buster seemed to find in his quiet third act, I worry whether that's a mission Cruise should choose to accept. [5]

July 23rd, 1926 was declared a local holiday by the city council of Cottage Grove, freeing everyone to attend the filming of The General’s big train wreck down in Row River. Having directed and starred in seven successful features in a row, Buster may have understood how McQuarrie felt, that he’d earned the right to torch over half a mill on this one shot, with no chance for retakes. He'd been a successful professional entertainer for over twenty-five years at this point, which makes it easy to lose track of the fact that he was a mere 30 years old that day. This whole directorial saga would be over before he turned 35.

Buster Keaton was 4 when he first stepped in front of a crowd, before Chaplin or even Mary Pickford had begun their careers. He’d already spent his life traveling with medicine shows but now his father Joe had pulled him into their struggling family vaudeville routine. By 5, Buster was the star of the show, his prodigious fame already sufficient to support his entire family, including sending his siblings to school (so long that Buster stayed on the road). An advertisement from the time announces:

Mr. and Mrs. Joe Keaton, formerly a noted sketch team, known all over the land as “The Man with the Table,” have added an attraction little BUSTER, the tiny comedian, who has made millions laugh.

Joe Keaton’s “table act” involved jumping on and off a table in increasingly dangerous ways, and descriptions portray Joe as less acrobat and more brute, willing to tolerate extreme injury in order to make up for any lack of finesse — a variable factor based on how hard he’d been drinking. Joe made no exceptions for Buster when he joined as The Boy Who Could Not Be Damaged in the rebranded The Roughest Act That Was Ever in the History of the Stage.

Their typical routine involved Buster cleverly flouting his father’s authority as they chased each other about, with Joe eventually catching hold of the boy and chucking him clear across the room in a sort of proto-Jackass. Critics found it worrisome to witness:

It’s a wonder to the uninitiated how the youngster keeps from getting killed. He is thrown about, kicked and cuffed, pitched around and mixed up generally in a rough and tumble manner that would apparently kill him half a dozen times during the performance, but he turns up smiling each time none the worse for the wear.

Even late in life Buster would still brag about how extreme they’d get:

We were the roughest knockabout act that ever was in the history of the theater, not only in the United States but all of Europe as well. We used to get arrested every other week — the old man would get arrested, see. […] But the law read that, “he can't do acrobatics, he can't walk a wire, he can't juggle” — a lot of those things, but there was nothing said in the law that you can't kick him in the face, or throw him through a piece of scenery!

If this sounds like exaggeration, well, you should be suspicious because Joe Keaton is a genuine American huckster, prone to making wild fabrications in order to promote the family’s act. But, at this time Buster became a literal poster child for the burgeoning discourse on labor laws for minors, and he was constantly pulled into court and made a spectacle:

So, on that technicality, we were allowed to work, although we’d get called into court every other week, see. Once they took me to the mayor of New York City, into his private office, with the city physicians here in New York, and they stripped me to examine me for broken bones and bruises. Finding none, the mayor gave me permission to work. The next time it happened, the following year, they sent me to Albany, to the governor of the state. Then in his office, same thing: state physicians examined me, and they gave me permission to work in New York State.

Buster always remembers these stories with amusement, thrilling in the hijinks involved with evading the law.

During these years, the larger the crowds Buster could bring in, the easier everyone in his family lived. Mass-market appeal and filial obligation were one and the same for Buster, and every day’s performance became a new chance to make his father proud by squeezing out an extra laugh here and there, refining each component of his “dream state” engine.

He also remembers his father as angry and drunk, with the on-stage antics increasingly becoming an arena for working out genuine resentments. You’ll find tales of young Buster being pacified with alcohol, or made to sleep in a suitcase to save a buck. I’m sure it was wonderful and miserable all at once, but eventually Joe’s alcoholism and depression become severe enough for Buster to break off on his own:

Yet you have to say, “Poor son of a bitch, fighting something he’d never catch up with!” But sweet Jesus, our act! What a beautiful thing it had been. That beautiful timing we had—beautiful to see, beautiful to do. The sound of the laughs, solid, right where you knew they would be… but look at what happened, standing up and bopping each other like a cheap film. It couldn’t last that way.

Much of my love and appreciation for Buster was stoked by Dana Stevens’ remarkable book Camera Man, which positions his life as a lens through which we can see the entire history of cinema. He was born in 1895, the same year the Lumière brothers first screened motion pictures to a paying audience. He lived long enough to see the rise and fall of the studio system that chewed him up and spat him out. He mentored Lucille Ball and lived to see the advent of color television before passing in 1966. For me, Buster Keaton seems to embody a nearly cosmic alignment of talent in acting, directing, writing, producing, editing, but also the character of man he was, the body he had, and the time, place, family, and culture into which he was born. The whole universe can only organize itself around a few people at a time.

The name “Buster” itself is one of Joe Keaton’s most notorious fabrications, a claim that Harry Houdini bestowed the sobriquet after witnessing the boy tumble. They did know Houdini, but it’s likely as legit as Joe’s story that Buster was blown four blocks away in a tornado as a baby. “The Great Stone Face” was his other popular nickname at the time, owing to his trademark reserved expressivity. Buster always explains that he keeps things bottled because that’s just how audiences preferred it.

Watching Buster act through a modern cinematic lens, one is more likely to conclude that it’s really everyone else that seems to be over acting, falling back to the theatrical need to play to the cheap seats. The intimacy of the camera affords reservation, and it's hard to say whether Buster lucked into this alignment or whether he could perceive how well his mannerisms transferred.

It’s not that Buster had no frame of reference for movies. He praised Chaplin, who had started directing a few years prior, and Buster got his start studying under his brilliant collaborator Roscoe Arbuckle. Even as a young child on vaudeville he’d share billing with “realities” — short films depicting documentary subjects, and the earliest commercial films anyone could be exposed to. When it came time to make movies of his own, everything about his violent amazing childhood seems to have equipped him with the skills and instincts needed to become one of the great masters in just a few years.

When asked in 1921 about his resistance to smiling he answered:

Not that I believe in weeping but people get a lot more enjoyment in watching me on the screen if I don't wear a stand-up-and-starched silly grin throughout the picture.

Sometimes, when I go to a theatre and see some comedian grinning after he has finished some stunt, it makes me feel the same as when I hear some fellow who admits he's witty, tell a funny story and then get in the first laugh on it. Still, it's being done by some of our very best comedians and I'm not criticizing them for showing their molars whenever they see fit.

Tom Cruise wasn’t working in entertainment by age four, but not for lack of wanting:

I remember as a kid, I was four years old and I wanted to make movies, and I wanted to fly airplanes. I thought about my life and I wanted to have adventure in my life. I was always a kid that was doing wild things, climbing the tallest trees, and I was very much a dreamer.

Tom would eventually come to share his dream of making movies and flying airplanes with us, but when the pitch first came his way he hesitated. In a Rolling Stone profile for Top Gun’s release, Tom talks openly about his disappointment making Legend, feeling like he was just “another color in a Ridley Scott painting.” Legend's production was a true disaster, with the film's entire forest set burning down completely with only ten days left in shooting. The film was completed, but in classic Ridley form it came in overlong, was cut to pieces, and flopped.

Next time around, Cruise would insist on locking in a screenplay that would hold the movie to a vision he believed in, a polar contrast to McQuarrie’s Tom, the “mind-reading, shapeshifting, incarnation of chaos,” as Ethan is described in DR.

Cruise made an unusual offer to the [producers]: he wanted to work on the script with them before deciding to commit to the project. “I said, ‘After two months, if I don’t want to do it? The script’s gonna be in good enough shape, and you’ll have more of a sense of what you want to do. And there are other actors.’ I think they were kind of taken aback at first, [but] after coming off Legend, I just wanted to make sure that everything was gonna go the way we talked about it.”

Cruise locked onto his target:

But the key problem was Cruise’s character: Pete “Maverick” Mitchell, a spiky-haired rogue whose antics are too reckless for his fellow flying aces. From the beginning, the role showcased Cruise’s ineluctable energy and, at least occasionally, his handsome face (the flyers wear masks for much of the film).

The chief worry was the asshole factor — how could Maverick be ultracompetitive and still be likable? Toward that end, Cruise and company created scenes in which Maverick reveals his self-doubts to his flying buddy. And a subtext for Maverick’s actions was established — his need to prove himself and to discover something about his father, lost mysteriously on a mission over Southeast Asia in the Sixties.

Tom was 12 when his parents divorced, and his mother struggled to provide for four children on her own:

Mary Lee refers to the divorce today only as “a time of growing, a time of conflict.” It was also a time of poverty. With precious little income, she and the children returned to Louisville and tried to start their lives again. “You know, women have dreams of having careers and being whatever,” Mary Lee says. “I had a dream of raising children and enjoying them and having a good family life.”

The article also describes his mother as a “vivacious, outgoing, religious woman who was a talented actress.”

“I was always interested in theater, but I never did anything with it,” she recalls. “When I was growing up, if you went to Hollywood, that was really risque. I would have lost my religion, my morals, all those things that young girls thought of back then.”

In 2010, Tom Cruise gave an interview to Esquire which is presented as a first-person pseudo-essay stripped of the interviewer’s questions. The editing slants it with a tender, direct tone you’ll never hear from Tom organically:

There was always food on the table. But there was no money. Every time my birthday was coming, I'd ask for a go-kart or a minibike. My mom's way of saying it wasn't going to happen was to ask me what kind of cake I wanted. That's what I got — the kind of cake I wanted and a trip to the movies.

His reminiscence at Cannes in 2002 is similarly structured out of self-conscious Hero’s Journey beats:

When I grew up I had jobs, not in the movie business, but I had to have jobs as a kid. Not I had to, but we also, I contributed to the family, but I cut grass, shoveled snow, I would sell cards door to door, like Christmas cards, seasonal cards.

I’d save my money, and I’d go to the movies. I’d give a little money to my family and go to the movies, give a little money, go to the movies.

At age 14, Tom joins a seminary and is “instantly hooked” but is later asked to leave when he conspires to steal alcohol from the Franciscan priests.

At age 16, Tom’s mother Mary Lee marries Jack South, who funds Tom’s move to New York City at 18 to get his start at acting. (Jack later separated from Mary Lee when she joined Scientology.) His biological father pleads no contest to Rolling Stone:

Tom and I are not in contact. I can’t take any credit for his success. I’m the last person who’ll ever criticize him. Maybe that’s one favor I’ve done for him.

Cruise talks about living a life of permanent first impressions:

“After a divorce, you feel so vulnerable,” says Tom, tossing his ice-cream cone away as he crosses 14th Street. “And traveling the way I did, you’re closed off a lot from people. I didn’t express a lot to people where I moved. They didn’t have the childhood I had, and I didn’t feel like they’d understand me. I was always warming up, getting acquainted with everyone. I went through a period, after the divorce, of really wanting to be accepted, wanting love and attention from people. But I never really seemed to fit in anywhere.”

In Esquire he explains how his family became both his friends and his audience:

You hear about people who have lifelong friends. I never was in a place long enough to have them. So that role was filled by my family. If anyone was teasing my sisters, I really felt it. I tried to develop a kind of calm in the presence of confusion. I'd create different characters and ad-lib sketches to make my sisters and my mother feel better. I'd try to make them laugh. I’d do Donald Duck as John Wayne. I'd watch Soul Train and imitate the dancers. If I went to a movie, I’d come home and do it for them. I guess you can say that’s where it started.

Rolling Stone describes the moment Tom learned his father was dying:

Tom was in Los Angeles, about to go to London for Legend, when the phone rang. “You know how sometimes the phone rings and — ping! — you just know?” He knew. His father was dead. “It cleared up a lot of kind of fog that I had about the man,” says Tom of his final meetings with his father, as he walks along 5th Avenue. “I think that he felt remorse for a lot that had happened. He was a person who did not have a huge influence on me in my teens; the values and motivation really came from my stepfather. But he was important. Really important. It’s all sort of complex. There wasn’t one thing I felt.”

Cruise had decided to do Legend just before his father died. “After what I was going through emotionally, facing death and all of that,” he says, “somehow it was important for me to try to get back to the innocence within my own soul.” He sighs. “I’m just glad I had acting then. I don’t know what I would have done without my work. It gave me a place to deal with all those emotions.”

I’m not sure what to say about an entire idyllic forest filled with unicorns burning down around Tom’s attempt to return to the innocence within his own soul. Decades later in Esquire, Tom revisits the moment:

I hadn't seen my father in about ten years. I found out he was dying, and I went to see him in the hospital. He knew. My mother is very special, and he knew that he'd blown it. There was deep regret. I think he was torturing himself. We tend to do that. All I could do was tell him, "Look, it's okay." I wasn't going to live in blame and regret. I wanted to understand what happened. I wanted to understand, so I could answer the question, What can I do to make things better? I looked at my father there dying and thought, How can I not be that guy?

The things you remember are the little things. The time he told you that he'd take you to a ball game and we didn't go. You said you were going to do it. "No,” would've been better than "I'm gonna do this with you,” and then not being there.

So you think, Who am I? What are the little moments that I want to create to reflect on my life?

One man’s trains are another man’s planes and it’s hard not to conclude that Buster and Tom’s respective trajectories were both set by infancy. At Cannes, Tom shared another memory:

I think I was about four-and-a-half years old, and I had this doll, and you throw it up in the air and a parachute comes down. I played with this thing, and I’d throw it off a tree, and I was like, ‘I really want to do this.’ I remember taking the sheets off my bed, and I would tie a rope... and I climbed up to the eave, and I got up to the roof. I looked and my mother was in the kitchen — she had four kids — and I jumped off the roof. It’s that moment when you jump off the roof and you go, ‘This is not gonna work. This is terrible. I'm gonna die.’

And I hit the ground so hard. Luckily, it was wet. I don't know how it happened, but I figured out after that my face went past my feet as my ass hit the ground. And I saw stars in the daytime for the first time, and I remember looking up, going, ‘This is very interesting.’

In his memoir Never Grow Up, Jackie Chan describes aiming high from a young age:

Neighbors would ask me what I wanted to be when I grew up, and I’d say I wanted to be a flying man. They’d say, “Flying how?” I'd point at the sky and say, “Flying very high!” They'd laugh and tell me not to fly yet, that I'd hurt myself. “Wait until you're grown up!”