This Passover, American Jews should embrace the fight for “emancipation of all kinds.”

This essay is adapted from Fear No Pharaoh: American Jews, the Civil War, and the Fight to End Slavery, by Richard Kreitner, published by Farrar, Straus, & Giroux.

This Passover, as for thousands of years, Jews gathered around seder tables will recall the story of our ancestors’ enslavement in Egypt. The purpose of remembering, however, is a little unclear, and, in our time, hotly contested: Is the lesson that we should do whatever is necessary to avoid being oppressed again—or is it that all forms of subjugation are inherently wrong and unjust, and that Jews should seek to end oppression for everyone?

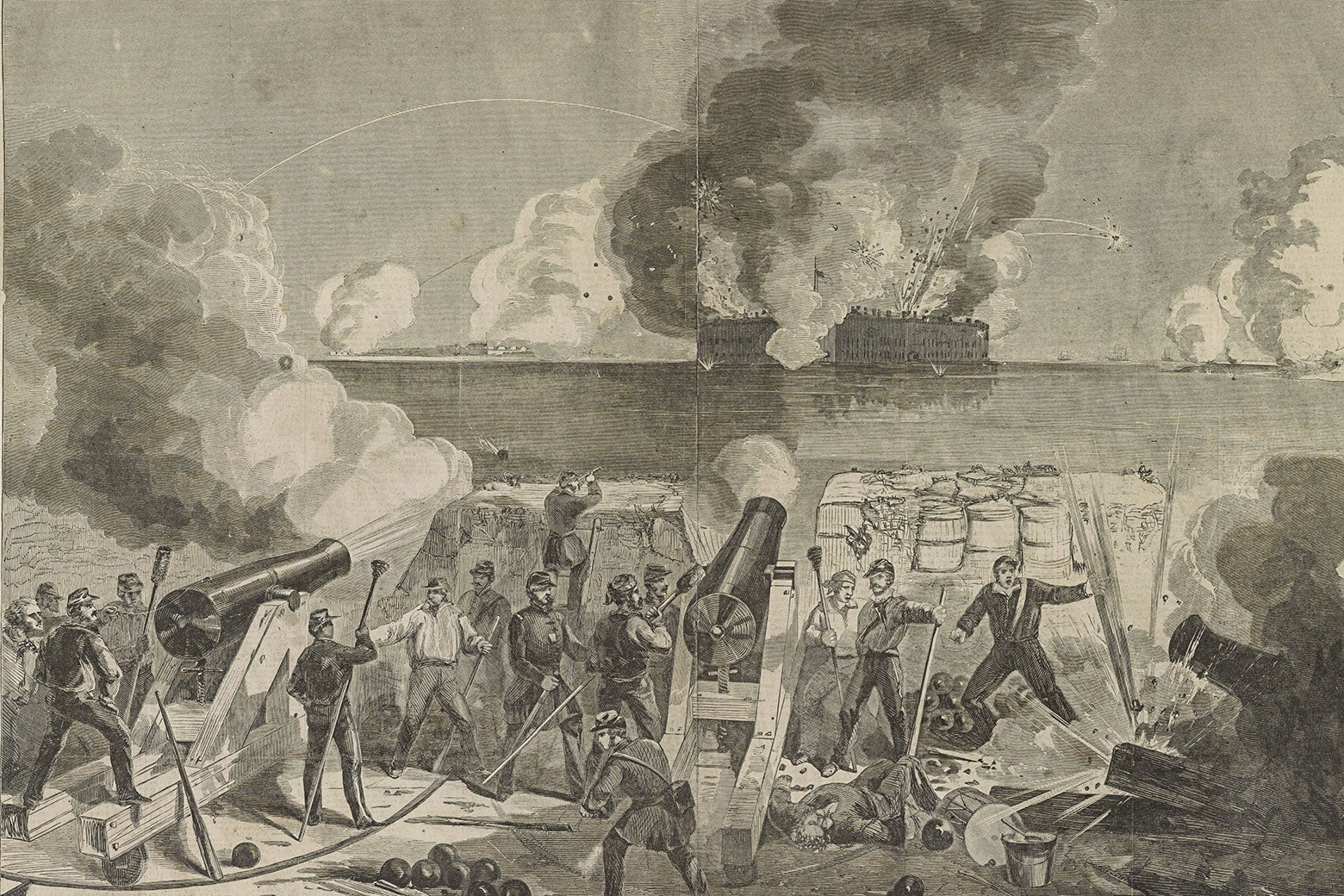

Today, this question bitterly divides the Jewish people. But it is not the first time it has done so. Passover begins this year on April 12, the 164th anniversary of the Confederate bombardment of Fort Sumter, which ignited the American Civil War. That night in 1861 was also the first night of Passover, and it found the 150,000 Jews who lived in the United States at the time similarly divided over what the principles of Judaism and the lessons of Jewish history had to say about the existence of Black slavery and the fracturing of the Union.

By Richard Kreitner. Farrar, Straus, & Giroux.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

For some Jews, protecting the precarious foothold they had gained in America was of paramount importance. They cherished the freedom their newly adopted country afforded them and saw the radical movement known as abolitionism as a threat to national unity. It didn’t help that leading abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison occasionally heaped scorn on Jews as “lineal descendant[s] of the monsters who nailed Jesus to the cross.”

But there were also anti-slavery Jews who were bothered by the fact that even as their newly adopted country offered freedom to them, it denied freedom to millions of others solely on the basis of their race. They argued that by participating in the enslavement of other human beings or even by staying silent about it, American Jews were agreeing to let questions of race and identity determine who deserved the protection of the government. Ultimately, they were endangering themselves.

In 1858, a Northern opponent derided Sen. Judah P. Benjamin of Louisiana, a former plantation owner and prominent defender of slavery, as an “Israelite with Egyptian principles.” He wasn’t the only one. Many early American Jews, especially in the South, embraced slavery wholeheartedly. Year after year, they sat down to Passover seders cooked and served by enslaved people, without the slightest sense of contradiction or unpleasant pang of guilt.

The extent of Jewish involvement in the slave trade and antebellum bondage has been exaggerated by antisemites of all stripes. The truth, inconvenient both for reflexive defenders of the faith and for its hate-filled foes, is that Jews were neither disproportionately invested in slavery nor consistently opposed to the institution. Conflicted and divided, implicated and appalled, Jews were pretty much like everyone else. Yet their peculiar history of oppression gave them a distinct relationship to slavery and to the struggle over its future.

In 1861, two weeks after South Carolina seceded from the Union, Morris Jacob Raphall, the Orthodox rabbi of B’nai Jeshurun synagogue in New York, gave a sermon proclaiming that the Hebrew Bible endorsed slavery. While laws limited how long slaves could be held and how cruelly they could be treated, the Torah did not ban the practice outright. Raphall pointedly asked abolitionists, “Does it not strike you that you are guilty of something very little short of blasphemy?”

Other prominent Jewish leaders knew that slavery was wrong yet opted not to say anything against it. Desperate not to embroil a small, vulnerable immigrant community in an intense national controversy, they tried to avoid the issue. After the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, Isaac Mayer Wise, an early leader of Reform Judaism, published an editorial titled “Silence, Our Policy.” As a resident of Cincinnati, poised on the border between slavery and freedom, Wise believed it was better for Jews not to get involved at all.

Yet for a handful of Jews, silence about slavery was not an option. Both because of Judaism’s much-touted ethical precepts and because of the horrors of oppression its adherents knew so well from their own history, they believed that Jews had a special obligation to resist injustice, even at the risk of inviting the wrath of Christian neighbors.

“Have they read the harrowing history of their ancestors’ bondage in Egypt to no purpose?” one writer in a Jewish periodical asked of pro-slavery Jews. “Have the merciless persecutions and unutterable tortures of the dark ages not yet opened their eyes and enlarged their heart for the alleviation of their fellow men’s woes?”

Even those Jews who disavowed biblical inspiration for their anti-slavery activism claimed special authority to denounce oppression because of the suffering of the Jewish people. Within months of her 1836 arrival in New York, Ernestine Rose, a Polish-born rabbi’s daughter, began traveling around the United States condemning women’s subjugation, economic inequality, organized religion, and chattel slavery. A proud unbeliever—she often spoke at atheist or “Infidel” conventions—Rose nonetheless cited her own background as evidence of “the universality of our claims,” identifying herself as “a daughter of poor, crushed Poland, and the down-trodden and persecuted people called the Jews.”

“I go for emancipation of all kinds,” Rose said, “white and black, man and woman. Humanity’s children are, in my estimation, all one and the same family, inheriting the same earth; therefore there should be no slaves of any kind among them.”

The most pointed Jewish response to Morris Raphall’s pro-slavery sermon came from David Einhorn, a Reform rabbi who bravely denounced the institution though he lived in Baltimore, the largest city in the northernmost slave state. To Einhorn, pro-slavery Jews like Raphall invited the enemies of the Jewish people to say, “Such are the Jews! Where they are oppressed, they boast of the humanity of their religion; but where they are free, their Rabbis declare slavery to have been sanctioned by God.”

Given their own sorrowful history, Einhorn argued, it was the Jews’ special obligation to fight against oppression and prejudice, not just for their own sake, but “for the whole world.”

In early 1861, as the nation went to war against itself, Einhorn’s Jewish critics in Baltimore called a meeting to protest his outspokenness, which they feared might draw negative attention. Einhorn explained it was precisely his concern to save the Jewish community from prejudice that compelled him to speak out when he saw it directed at others.

Days later, a pro-slavery mob destroyed the press that printed Einhorn’s monthly newspaper and went looking for the rabbi. Along with his pregnant wife, Einhorn sneaked out of town and took a carriage to Philadelphia. His congregation asked him to return, but only if he agreed not to comment on the “explosive questions of the day.” They wanted him to keep silent about slavery. Einhorn refused, bitterly denouncing his opponents: “The light of the Rabbis becomes a destroying torch in the hands of such people.”

Einhorn never returned to Baltimore. As the war escalated that first summer, he predicted that “the next battles will leave a real blood bath, but slavery will be drowned in that bath.”

The Passover seder calls on Jews to remember our ancestors’ enslavement in Egypt, but the question of what to do with that memory has never been easy to answer.

In 1861, Jews found themselves torn between competing conceptions of self-preservation and justice.

This year, in another moment of communal division and moral crisis, the coincidence of the first seder with the anniversary of the Civil War’s first shots reminds us that the choices we face now are not so different from those that American Jews faced back then. As we meditate on pressing ethical and political questions around the seder table this year, let us recall the example of those who encouraged us to enlarge our hearts and to fight for emancipation of all kinds.

Sign up for Slate’s evening newsletter.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·