This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

Honor Jones’s debut novel, Sleep, starts with a child’s perception of the world around her. I’ve known Honor, a senior editor at The Atlantic, since we were both children, and reading the book was a little like immersing myself in our own long friendship. I asked Honor a few questions about Sleep, which is out today. You can buy it here.

Walt Hunter: I think I was one of the first people to read the whole novel—is that right?—which is an incredible gift for an editor, not to mention a friend. You’re an editor, too, and a journalist. What are the differences, for you, between writing fiction and writing nonfiction?

Honor Jones: You were! And you gave me the most brilliant notes. We go back: I’ll remind you and everyone else here that you also read and advised me on my thesis in college! I see how the idea of moving from fact to fiction could feel really unmooring, but I basically think that writing is writing—you’re always thinking about voice, about structure. What really matters is that you have a purpose: something that needs to be said or done in the text. If that’s the case, then there’s always something dictating what the story needs, even if, instead of news or history, it’s only the demands of the story itself.

That said, it was hard—and exciting—to try to leave my journalist self out of the sentences. I had to go through and cut like a thousand commas out of the book. During the editing process, I also accidentally called the book title “the headline” so many times that it started to get embarrassing.

Walt: When I think about the novel, the first thing I think about is your style. What does a novel allow you to do that a news story doesn’t?

Honor: One thing it lets you do is write what a character is thinking and feeling about what’s happening, even when she doesn’t understand what’s happening. This was important because the beginning of the book is told from the perspective of a child. I also felt that I was often exploring an idea that I couldn’t argue or defend. A novel is a good place for that, especially if the idea is weird or perverse or otherwise hard to talk about.

Walt: The main character, Margaret, is a sharp observer of her world—someone “on whom nothing is lost,” to borrow a phrase from Henry James. We start the book in the dampness under a blackberry bush—such a tangible detail!

Honor: I knew that I didn’t want the child in this story to be special or precocious. She has no exposure to the world of art or ideas. She knows next to nothing about history or politics. She’s growing up in the ’90s, and I have this line about her education lying entirely on a foundation of American Girl–doll books. She simply has no context for what happens to her. But she’s trying really hard to make sense of it anyway. She’s naturally probably a perceptive kid, but she’s also that way because she has to be, because she learns that she has to protect herself.

And I think that sense of watchfulness defines her as she grows up. In the sections that follow, she changes in all these ways while remaining fundamentally the same person. I was interested in that—how she can’t shake her own history, how many of her choices as an adult are defined by the events of her childhood, how she has to learn to be a mother while remaining a daughter.

Walt: The novel is also psychologically astute in any number of ways. For example, we watch the friendship between Margaret and Biddy as it develops over a long period of time. And Margaret’s relationship with her family members is, of course, at the center of the book. What are you exploring with these long-term ties?

Honor: I loved writing this friendship! You can probably recognize aspects of the girls we both grew up with in the character of Biddy. She’s sort of a composite of all the best friends I’ve loved through life, while also being her own person—ballsier and bolder than any of us were at that age. Biddy really is Margaret’s family, the person who stays alongside her through all the years. One thing I find freeing about their relationship is that, even though Margaret keeps this terrible secret from Biddy, in some ways, it doesn’t matter. The novel is so concerned with the danger of secrets and the power of disclosure, but Biddy just loves Margaret. She is the one character for whom the truth would change nothing.

A lot of the book is about Margaret trying to understand the people around her, but people don’t really explain themselves. (Margaret doesn’t, either—people keep asking her why she got divorced, and she never has any idea what to say.) When she finds the courage to ask what is maybe the most important question in the book, the answer she gets is profoundly insufficient. I think some readers might find that frustrating, and would rather the book build up to a final confrontation and resolution. But that’s not what I was interested in. I think trying to understand, failing to understand, knowing a little more, knowing yourself better—that’s what it’s about.

Walt: The first part of Sleep is set in a place—wealthy suburban New Jersey—where social class has an infinite number of near-invisible gradations. It reminds me a lot of where we grew up, on the Main Line outside Philadelphia. You manage to sneak in so many small details—of decor, especially, but also of social decorum—that reveal these distinctions. They make sense to me, the child of a reporter, whose family never quite fit into the whole milieu. And I recognize myself a little in Margaret—she’s not entirely comfortable among the heirs and heiresses. But of course the book is also very tender, in its way, to the people in it. Why write about this place, these people? What did you learn?

Honor: The thing that really marks her as an outsider in this social world and class happens when she grows up and gets divorced. But she’s always felt like an outsider and an observer, as you say. I wanted to show how, as a child, she’s learning about class as if it’s just another language. Why does her mother care so much about this particular neighbor? What are they conveying by having this particular pet? It was fun to write about all this signaling from people who are quite incapable of communicating in other ways.

Walt: One scene that sticks in my mind—that really keeps me up at night, sometimes—is the one at the party in Brooklyn where we almost suspect that Margaret’s child might be in danger. There’s genuine suspense there, even some terror.

Honor: I think the big question of this book is: How do you raise a child to be safe without raising them to be afraid? What’s the right amount of vigilance? Should you—can you—trust the world? I think this feeling of domestic horror will be familiar to a lot of parents. It’s a lovely day on the playground, and then suddenly you look up and you can’t find your kid. He’s fine! He’s just behind a tree or whatever. But immediately you’re aware of the worst-case scenario. Terror is always an option, and those darker feelings lie right up against the joy and fun of parenting. I think there’s a lot of the latter in the book, too.

Walt: Does fiction have an ethical responsibility when it comes to representing a moment, or repeated moments, of trauma? What is that responsibility?

Honor: If there’s anything I think fiction shouldn’t tolerate, it’s squeamishness. In Sleep, for instance, I had to say what happened to Margaret. I had to describe it in simple language. It had to happen in the beginning of the book. Her particular form of trauma is quieter than many others—there is no violence, for instance. But it’s still insidious. Margaret might not understand what’s happening, but I wanted the reader to know. You could imagine a different story: a divorced woman’s self-doubt, a mystery unfolding, a revelation of memory … but I could not have written that book. It would have felt dishonest. The mystery isn’t what was done to her—it’s what she does with herself after.

Related:

Here are three new stories from The Atlantic:

Today’s News

- The Trump administration announced a nearly $142 billion arms sale to Saudi Arabia. In return, Saudi Arabia would invest $600 billion in America’s industries.

- President Donald Trump declared that he would lift sanctions on Syria, ahead of his visit with Syria’s new president.

- Russian and Ukrainian delegations are set to meet this week for their first face-to-face talks since 2022.

Evening Read

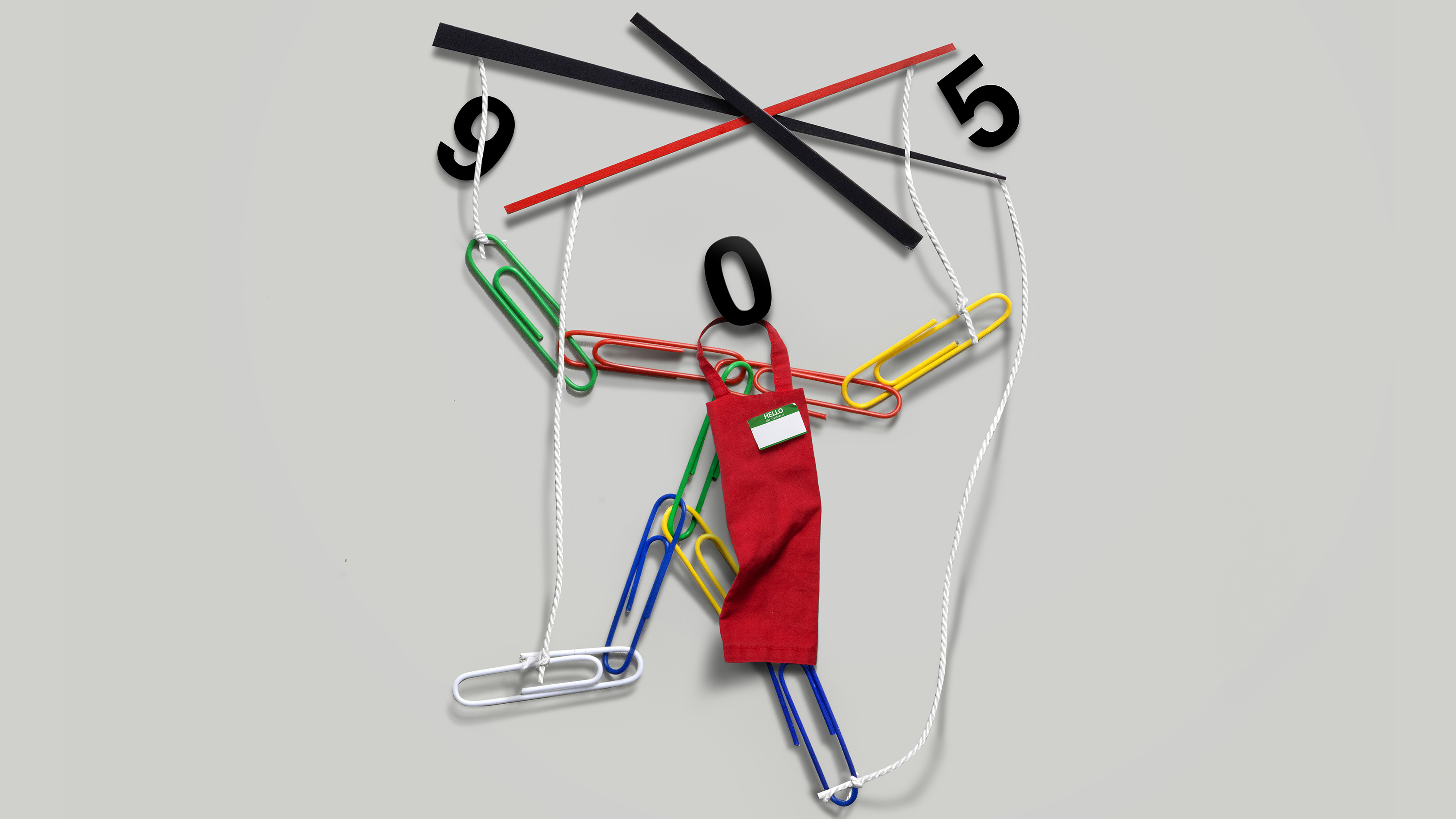

Illustration by Doug Chayka

Illustration by Doug ChaykaHow Part-Time Jobs Became a Trap

By Adelle Waldman

Several years ago, to research the novel I was writing, I spent six months working in the warehouse of a big-box store. As a supporter of the Fight for $15, I expected my co-workers to be frustrated that starting pay at the store was just $12.25 an hour. In fact, I found them to be less concerned about the wage than about the irregular hours. The store, like much of the American retail sector, used just-in-time scheduling to track customer flow on an hourly basis and anticipate staffing needs at any given moment. My co-workers and I had no way to know how many hours of work we’d get—and thus how much money we’d earn—from week to week.

More From The Atlantic

Culture Break

Warner Brothers / Everett Collection

Warner Brothers / Everett CollectionWatch. These are 25 of the best horror films you can watch, ranked by scariness, David Sims wrote in 2020.

Discover. Gregg Popovich, former head coach and current president of the San Antonio Spurs, shared his life lessons with Adam Harris.

Stephanie Bai contributed to this newsletter.

Explore all of our newsletters here.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

1 month ago

4

1 month ago

4

English (US) ·

English (US) ·