Americans want to reduce sprawl, but how we actually build depends on the city.

Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

In 2007, architect Carl Elefante expressed an idea that has since become a common provocation in the world of architecture: The greenest building is one that’s already built. By which he meant that the carbon footprint of construction is so large—from material manufacturing to shipping to the energy of putting a new building together—that you would be better off with your drafty old house than even an airtight new box clad in solar panels.

Old buildings have something else going for them: They tend to be closer to other buildings, and closer to the center of the city. People who live centrally spend less time traveling every day. And while buildings themselves (U.S. commercial and residential structures) are responsible for 29 percent of the country’s emissions, the largest source of U.S. emissions still comes from transportation. That means the greenest new building is one that’s in the center of town.

That’s the climate argument behind the country’s various urban pro-housing movements, from “smart growth” and “transit-oriented development” to “missing middle” and “yes in my backyard.” But building housing where people can drive less will also save residents money (transportation is the second-largest household expense, after housing), political headaches (by reducing traffic), and even lives (car crashes are the leading cause of death for children and teenagers).

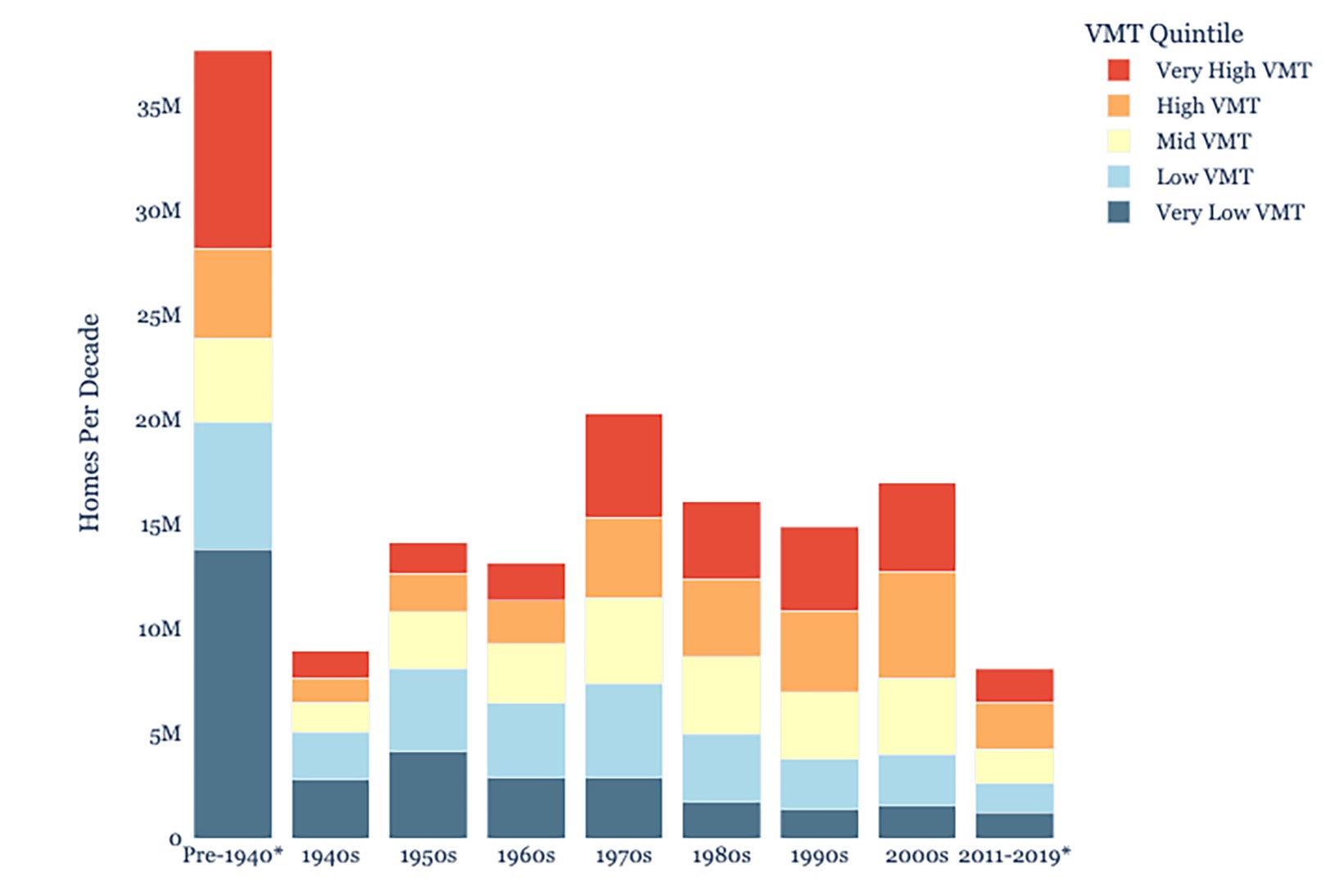

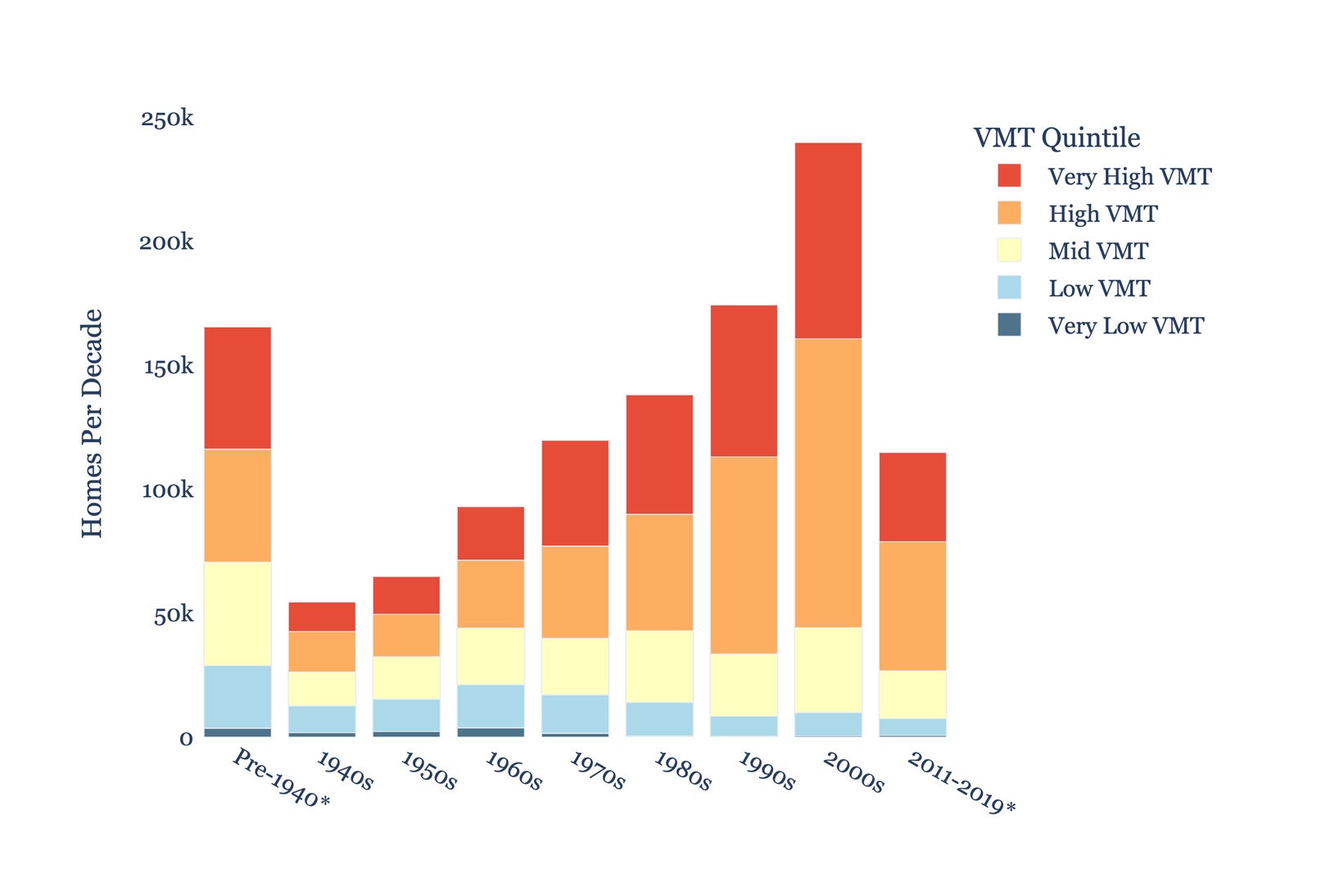

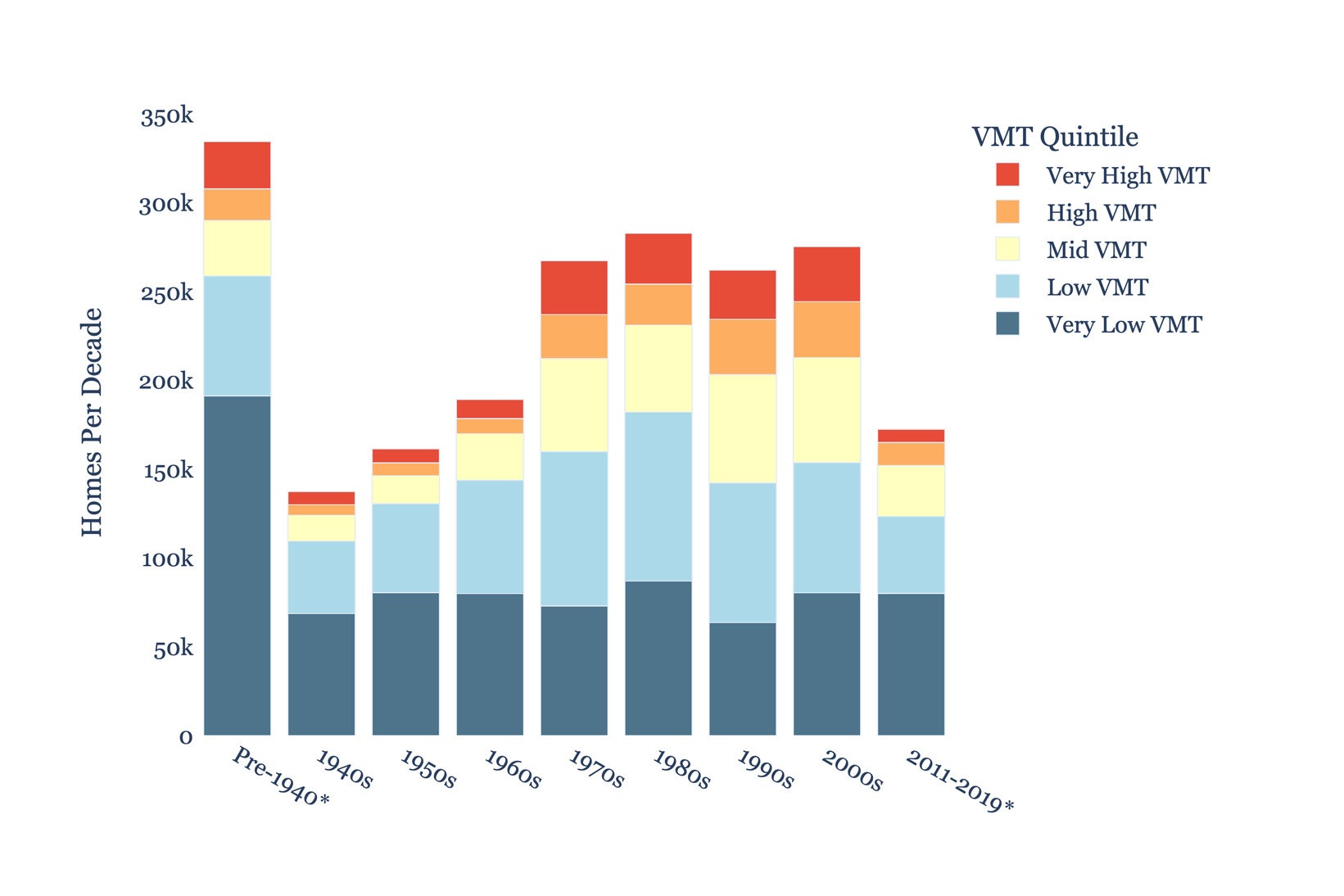

A new analysis from the UC–Berkeley’s Terner Center documents how the past few decades of anti-sprawl, pro-infill movement is coming along.

The results are a mixed bag. Authors Zack Subin and Quinn Underriner note that while the post–financial crisis decade (2011 to 2019) saw a relative shift toward construction in neighborhoods where people drive less (compared to homes built in driving zones), the absolute number of homes built in those neighborhoods was lower than in any decade in a century. To the extent infill grew its share of the pie, it was because the 2008 housing crash sent tract-home sprawl down to levels not seen since the Eisenhower administration.

Using driving data from Replica, the Berkeley team sorted neighborhoods into five categories according to how much residents drive. Even in the “very low vehicle miles traveled (VMT)” category, people drive quite a bit—12 miles per person, per day—but far less than in the high or very high categories (25.5 and 37.5 miles per person, per day, respectively).

Census data frames driving as a binary—either a respondent drives to work or they don’t. But the reality is that there’s lots of variation even within the category of car-centric cities: Someone in Charlotte (38.1 miles a day) or Jacksonville (35.7) drives much more than a resident of Los Angeles (20.2) or Indianapolis (22.7). For this reason, the Berkeley study’s breakdown between different levels of driving is pragmatic and refreshing. In terms of pollution and emissions, there’s a bigger difference between someone who drives 40 miles a day and someone who drives 3 miles than between someone who drives 3 miles and someone who rides a bike.

There is also considerable variation within metro areas, with low-mileage neighborhoods nestled in what is sometimes dismissively categorized as an undifferentiated mat of suburbs. Research from Brookings has shown that even in sprawling Dallas, residents near “activity centers” (such as malls or town centers) drive 15,000 fewer miles a year than their counterparts who live farther away. And the Berkeley analysis reminds us that even in the 1950s and ’60s, when sprawl was taking off, most housing was built in neighborhoods that today permit residents to drive less than average. Levittown and Little Boxes, welcome to the war on cars!

Who is building housing in these low-mileage neighborhoods? Subin and Underriner draw out different “types” of cities: New York City isn’t building much, but the housing it does build permits people to drive little. Even though the New York metro area covers four states, an extensive transit network helps keep driving miles low even in the areas that grew during the ’90s and ’00s. Charlotte, by contrast, has added lots of housing downtown—but with an underfunded transit system and a sprawling geography of jobs, people still drive a lot, upward of 25 miles a day.

Five large metro regions have kept up their housing growth and built much of that housing in neighborhoods where people don’t have to drive so much, and they’re not all the usual suspects: Portland, Seattle, Salt Lake City, El Paso, and Miami. They have different things going for them: El Paso is relatively small and has a higher urban density than peers like Austin. Seattle, Portland, and Miami all have urban growth boundaries, while El Paso butts up against the Mexican border. Salt Lake City, perhaps, benefits from its natural position between two mountain ranges. (The research period ends in 2019, so more recent infill land-use reforms in places like Portland or Salt Lake City aren’t included.)

If limiting pollution, emissions, crashes, and the expense of driving isn’t enough reason to encourage more housing in these areas, consider also self-interest. In 2023, a poll in Sacramento showed that Americans were more concerned about traffic and parking than neighborhood character, school overcrowding, or crime. And the neighborhood that creates the least traffic? It’s the one that’s already built.

Sign up for Slate's evening newsletter.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·